Maxillofacial surgery, often referred to as oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMS), is a specialized field of medicine that focuses on the diagnosis, surgical treatment, and management of diseases, injuries, and defects affecting the mouth, jaws, face, and associated structures. This discipline stands at the crossroads of dentistry and medicine, requiring practitioners to possess knowledge and skills that span both domains. The scope of maxillofacial surgery is vast, encompassing procedures from wisdom tooth extractions to complex facial reconstructions following trauma or cancer.

Introduction

Maxillofacial surgery is a cornerstone of modern healthcare, addressing both functional and aesthetic aspects of the craniofacial region. Surgeons in this field play a critical role in improving patients’ quality of life, whether by restoring the ability to speak and eat or by reconstructing facial features. As a specialty, it is unique in that it requires dual training in both dentistry and surgery, reflecting the complexity of the anatomical areas it addresses.

History of Maxillofacial Surgery

The roots of maxillofacial surgery trace back to ancient times, with early documentation of jaw treatments found in Egyptian and Greek writings. However, the specialty as it is known today began to take shape during the world wars of the 20th century. The high incidence of head and facial injuries led to advances in surgical techniques and the development of reconstructive procedures. Pioneers such as Sir Harold Gillies and Dr. Varaztad Kazanjian are renowned for their groundbreaking work in reconstructive surgery, laying the groundwork for contemporary maxillofacial practices.

Training and Education

Becoming a maxillofacial surgeon requires extensive education and training. In most countries, this involves:

- Completion of dental school (DDS or DMD degree)

- Additional medical degree (MD), required in some regions (e.g., United Kingdom, Australia)

- Residency program in oral and maxillofacial surgery, typically 4-6 years in duration

- Fellowships in subspecialties such as craniofacial surgery, cosmetic surgery, or oncology

Maxillofacial surgeons must master surgical skills in both hard (bone) and soft (tissue) anatomy, and develop proficiency in anesthesia, as many procedures are performed under sedation or general anesthesia.

Scope of Maxillofacial Surgery

The field of maxillofacial surgery covers a broad spectrum of conditions and procedures, including but not limited to:

Dentoalveolar Surgery

This includes routine and complex extractions (such as impacted wisdom teeth), management of dental infections, and pre-prosthetic surgery to prepare the mouth for dentures or implants.

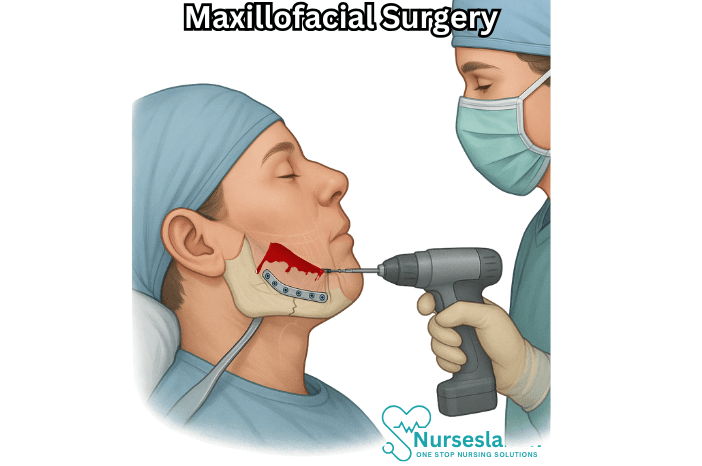

Trauma Surgery

Facial trauma is a significant component of maxillofacial surgery. Surgeons repair fractures of the jaw, cheekbones, nose, and orbital bones. They also manage soft tissue injuries such as lacerations and avulsions. The goal is to restore both function and appearance, minimizing long-term complications.

Orthognathic (Jaw) Surgery

Orthognathic surgery corrects congenital or acquired abnormalities of the jaw bones that affect chewing, speech, or facial aesthetics. Common indications include malocclusion (misaligned bite), sleep apnea, and facial asymmetry. These procedures are often planned in conjunction with orthodontists and require precise surgical techniques.

Reconstructive Surgery

Reconstruction is necessary following trauma, tumor removal, or congenital defects such as cleft lip and palate. Techniques range from bone grafting and local tissue flaps to complex microvascular free tissue transfer, where tissue from another body part is used to rebuild facial structures.

Oncologic Surgery

Maxillofacial surgeons are key members of head and neck cancer teams. They perform biopsies, tumor resections, and lymph node dissections, and collaborate with other specialists for reconstructive and rehabilitative care.

Cosmetic and Aesthetic Surgery

The specialty overlaps with cosmetic surgery in procedures such as rhinoplasty (nose reshaping), genioplasty (chin surgery), facelifts, and facial implants. The goal is to enhance facial harmony while preserving or improving function.

Management of Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Disorders

The TMJ is prone to a variety of disorders, including arthritis, dislocation, and internal derangement. Treatment ranges from conservative management to surgical intervention such as arthroscopy or joint replacement.

Implant Surgery

Dental implants have revolutionized restorative dentistry. Maxillofacial surgeons are experts in placing implants in the jawbone, often utilizing advanced imaging and guided surgery techniques for precision.

Techniques and Innovations

Maxillofacial surgery has seen remarkable advancements in recent decades. Innovations include:

- 3D imaging and virtual surgical planning, enabling precise diagnosis and simulation of complex cases

- Minimally invasive surgical techniques that reduce recovery times and improve outcomes

- Use of biomaterials and alloplastic implants for reconstruction

- Robotic-assisted surgery, which is emerging as an adjunct for certain procedures

- Regenerative medicine approaches, such as stem cell therapy and tissue engineering

Digital technology now allows for custom fabrication of prosthetics and implants, tailored to each patient’s anatomy. This convergence of medicine, engineering, and technology is rapidly expanding the possibilities in maxillofacial care.

Multidisciplinary Approach

Given the complexity of the craniofacial region, maxillofacial surgeons often collaborate with a wide range of healthcare professionals, including:

- Plastic and reconstructive surgeons

- Otolaryngologists (ENT specialists)

- Neurosurgeons

- Orthodontists and restorative dentists

- Oncologists and radiologists

- Speech and language therapists

- Psychologists and pain specialists

This collaborative approach ensures holistic care, addressing both immediate surgical needs and long-term functional and psychological outcomes.

Patient Experience and Recovery

Maxillofacial surgery can be daunting for patients due to the delicate and visible nature of the facial region. Preoperative evaluation includes a thorough medical and dental history, imaging studies, and discussions about expectations and potential risks.

Recovery times vary depending on the procedure. Simple tooth extractions may heal within days, while reconstructive or orthognathic surgeries require weeks or months for full recovery. Pain management, infection prevention, and rehabilitation (such as physical therapy or speech therapy) are integral to the postoperative process.

Challenges and Considerations

Despite advances in surgical techniques and technology, maxillofacial surgery presents several challenges:

- Managing complex anatomy with critical structures such as nerves, blood vessels, and the airway

- Balancing functional and aesthetic outcomes

- Addressing psychological impacts of facial deformity or trauma

- Ensuring access to care in underserved populations

- Staying current with rapidly evolving technologies and treatment protocols

Ethical considerations also arise, particularly in cosmetic and reconstructive cases where patient expectations may be high.

Nursing Care for Patients Undergoing Maxillofacial Surgery

The complexity of the anatomical region and the variety of potential complications necessitate a thorough, patient-centered approach to nursing care. This document aims to provide an in-depth exploration of the nursing responsibilities and interventions essential for optimal recovery and patient well-being following maxillofacial surgery.

Preoperative Nursing Care

Patient Assessment

- Obtain a detailed medical, surgical, and dental history to identify risk factors and comorbidities.

- Assess for allergies, current medications, and previous reactions to anesthesia.

- Evaluate nutritional status, as malnutrition can hinder healing post-surgery.

- Perform baseline vital signs and airway assessment to anticipate postoperative challenges.

- Screen for psychological preparedness and anxiety related to surgery.

Patient Education

- Explain the nature of the planned surgery, expected outcomes, and possible complications.

- Discuss postoperative appearance, potential swelling, and the presence of drains, wires, or fixation devices.

- Educate about pain management protocols and the importance of adhering to prescribed medications.

- Provide information on oral hygiene routines, especially if intermaxillary fixation is anticipated.

- Review fasting instructions and preoperative skin/oral preparations as directed by the surgical team.

Preparation for Surgery

- Ensure all laboratory investigations and imaging studies are complete and available for review.

- Obtain informed consent and verify that all documentation is complete.

- Prepare the operative site in accordance with aseptic guidelines.

- Initiate intravenous access for fluid management and administration of preoperative medications.

- Remove dental prostheses, jewelry, and contact lenses before transfer to the operating room.

Immediate Postoperative Nursing Care

Airway Management

- Monitor airway patency vigilantly, as postoperative swelling, bleeding, or displacement of tissues may compromise breathing.

- Position the patient with head elevated to decrease edema and promote drainage.

- Keep suction equipment and emergency airway supplies readily accessible.

- If intermaxillary fixation is used, ensure wire cutters are at the bedside for rapid release in case of airway obstruction or vomiting.

- Assess for stridor, dyspnea, or cyanosis and intervene promptly.

Pain Management

- Administer prescribed analgesics, utilizing both opioid and non-opioid medications as appropriate.

- Assess pain regularly using validated pain scales and observe for non-verbal signs of discomfort.

- Employ adjunct measures such as cold compresses and relaxation techniques to minimize pain and swelling.

Monitoring for Complications

- Observe for excessive bleeding, hematoma formation, or signs of infection at the surgical site.

- Monitor vital signs frequently, noting changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature.

- Check for facial nerve function, particularly after procedures near the parotid gland or mandible.

- Assess for difficulty swallowing, drooling, or aspiration, which may signal nerve injury or edema.

Fluid and Nutrition Management

- Monitor intravenous fluid therapy, ensuring adequate hydration while avoiding overload.

- Evaluate readiness for oral intake, starting with clear fluids and advancing as tolerated.

- If oral intake is not possible, assist with nasogastric or gastrostomy feeding as per physician orders.

- Collaborate with dietitians to provide high-calorie, high-protein nutrition to support healing.

Ongoing Inpatient Nursing Care

Wound Care and Infection Prevention

- Perform regular inspection and dressing of surgical incisions, noting redness, swelling, or discharge.

- Maintain strict aseptic technique during dressing changes.

- Administer prophylactic antibiotics when prescribed.

- Promote effective oral hygiene using antiseptic mouthwashes, soft toothbrushes, and irrigation as needed.

Mobility and Physiotherapy

- Encourage early mobilization to prevent venous thromboembolism and promote lung expansion.

- Assist with facial exercises and jaw physiotherapy as directed to prevent stiffness and restore function.

- Teach techniques for safe ambulation and self-care, particularly if the patient experiences dizziness or weakness.

Psychosocial Support

- Provide reassurance about changes in appearance and support adaptation to temporary or permanent facial alterations.

- Facilitate communication with family members and encourage their involvement in care.

- Refer to counseling services if the patient exhibits signs of depression, anxiety, or body image disturbance.

Patient Safety

- Implement fall precautions, especially in patients with impaired vision, balance, or sedation.

- Ensure all fixation devices remain secure and provide instructions on avoiding undue pressure to the surgical area.

- Educate on recognizing signs of complications and when to alert nursing staff.

Preparation for Discharge

Education and Follow-Up

- Teach proper wound care, oral hygiene, and medication administration at home.

- Provide a list of signs and symptoms for which medical attention should be sought (e.g., fever, increasing swelling, difficulty breathing).

- Discuss dietary modifications, emphasizing soft or liquid diets as appropriate.

- Arrange for outpatient follow-up with the surgical team, nutritionist, and physical therapist.

- Supply contact information for community resources or support groups addressing facial surgery recovery.

Special Considerations in Nursing Care

Pediatric Patients

- Assess developmental stage and tailor communication appropriately.

- Engage family members in care and education, especially regarding feeding and wound management.

- Monitor for behavioral changes that may signal distress or pain.

Geriatric Patients

- Screen for comorbidities that may influence healing (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease).

- Address challenges with nutrition and oral intake due to pre-existing dental or swallowing issues.

- Promote fall prevention and safe mobility strategies.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. OMS Procedures., https://www.aaoms.org/education-research/dental-students/oms-procedures.

- Mohanty R, et al. (2019). An analysis of approach toward oral and maxillofacial surgery: A survey of 1800 health-care specialists, students, and general people in Odisha, India.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6563626/ - Akinbami BO, Godspower T. Dry socket: incidence, clinical features, and predisposing factors. Int J Dentistry. 2014;2014:796102. doi:10.1155/2014/796102

- American College of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Conditions and Treatments., https://www.acoms.org/page/Conditions_treatment.

- American College of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. What is an Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon. https://www.acoms.org/page/What_is_an_OMS)?

- Kim YK. Complications associated with orthognathic surgery. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5342970/). J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017 Feb;43(1):3-15.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.