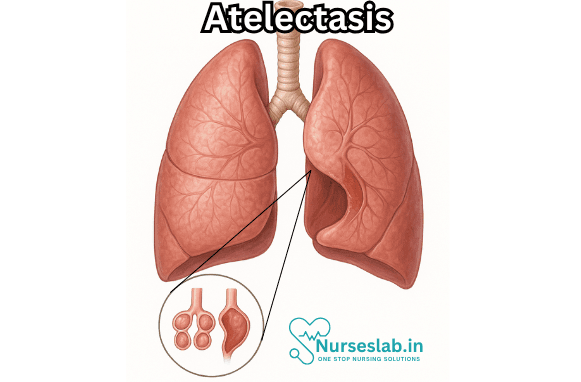

Atelectasis is a medical term referring to the partial or complete collapse of the lung or a section (lobe) of the lung. It is a common, often preventable, pulmonary complication that can occur in a variety of clinical contexts. The term is derived from Greek, in which “atelēs” means incomplete and “ektasis” means expansion, thus literally signifying “incomplete expansion” of lung tissue. Atelectasis is not a disease itself but a condition or sign that indicates an underlying process affecting normal lung aeration.

Understanding the mechanisms, risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of atelectasis is essential for healthcare professionals, as timely intervention can prevent significant morbidity and even mortality.

Pathophysiology

Atelectasis results from the loss of air in the alveoli, the tiny air sacs in the lungs where gas exchange occurs. When alveoli are deflated or filled with alveolar fluid, oxygen is no longer able to pass into the bloodstream from these areas. The exact pathophysiological process varies according to the cause of atelectasis, but generally, it involves a disruption in the balance between the forces that keep the alveoli open and those that favor their closure.

Several mechanisms can lead to atelectasis:

- Obstructive (Resorptive) Atelectasis: Occurs when an airway (bronchus, bronchiole) is blocked by a mucus plug, tumor, foreign body, or other obstruction. The trapped air in the affected alveoli is absorbed into the bloodstream, leading to collapse.

- Non-obstructive (Compressive) Atelectasis: Results from external pressure on the lung from pleural effusion, pneumothorax, tumors, or abdominal distension. This pressure compresses the lung tissue and leads to collapse.

- Adhesive Atelectasis: Occurs when surfactant, a substance that reduces surface tension in the alveoli, is deficient. This is commonly seen in conditions like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

- Cicatricial (Contraction) Atelectasis: Due to scarring or fibrosis in the lung tissue, which contracts and pulls the lung tissue inward.

- Passive Atelectasis: Occurs when there is loss of contact between the parietal and visceral pleura, such as in pneumothorax or large pleural effusion.

Causes and Risk Factors

Atelectasis can arise from numerous clinical situations, including:

- Postoperative Setting: The most common cause in hospitalized patients, especially after abdominal or thoracic surgery. Reduced lung expansion due to pain, splinting, anesthesia, and shallow breathing contributes to alveolar collapse.

- Obstruction: Mucus plugs, aspiration of foreign bodies (common in children), tumors, or thick secretions from chronic lung diseases (e.g., cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis) can block airways.

- Pleural Diseases: Conditions that fill the pleural space with air (pneumothorax), blood (hemothorax), pus (empyema), or fluid (pleural effusion) can compress lung tissue.

- Chest Wall or Neuromuscular Disorders: Diseases that weaken the muscles of respiration (e.g., myasthenia gravis, muscular dystrophy) or cause abnormal chest wall mechanics (e.g., scoliosis) may limit lung expansion.

- Surfactant Deficiency: Seen in premature infants with neonatal respiratory distress syndrome or adults with acute lung injury.

- Prolonged Bed Rest or Immobility: Inactivity leads to shallow breathing and decreased clearance of secretions.

Certain populations are at higher risk for developing atelectasis, such as the elderly, patients with underlying lung disease, smokers, those requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation, and infants with immature lungs.

Clinical Presentation

The signs and symptoms of atelectasis depend on the extent and rate of lung collapse and the underlying cause.

- Small Area Collapse: May be asymptomatic and detected only incidentally on imaging.

- Large Area Collapse: Can cause shortness of breath, rapid shallow breathing, cough, low-grade fever (especially postoperatively), chest pain, and decreased oxygen saturation. The affected side of the chest may appear sunken, and breath sounds may be diminished or absent over the collapsed area.

- Severe or Sudden Collapse: May lead to hypoxemia, rapid heart rate, cyanosis, or in severe cases, respiratory failure.

Diagnosis

Atelectasis is suspected based on clinical context and findings, but confirmation relies on imaging studies.

- Chest X-ray: The most common diagnostic tool. Findings include increased opacity (whiteness) of the affected lung area, shift of structures (such as the trachea or mediastinum) towards the collapse, elevation of the diaphragm on the affected side, and narrowing of the intercostal spaces.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides more detailed images and may help identify the cause, extent, and complications of atelectasis.

- Bronchoscopy: Used to visualize and potentially remove blockages within the bronchial tree.

- Pulse Oximetry and Arterial Blood Gases: Assess the severity of oxygenation impairment.

Clinical assessment includes a detailed history and physical examination, focusing on risk factors, recent surgeries, and evidence of respiratory distress.

Management

The treatment of atelectasis aims to re-expand the collapsed lung tissue and address the underlying cause.

- Prevention: Prevention is critical, especially in surgical and high-risk patients. Techniques include early mobilization, incentive spirometry, deep breathing exercises, adequate pain control, chest physiotherapy, and positive airway pressure therapies.

- Removal of Obstruction: If atelectasis is due to mucus or foreign body, interventions such as chest physiotherapy, suctioning, bronchoscopy, or nebulized medications may be necessary.

- Treating Underlying Conditions: Management of pleural effusions, pneumothorax, tumors, or infections may be needed.

- Supportive Care: Oxygen supplementation, hydration, and airway clearance techniques help maintain adequate oxygenation and promote lung expansion.

- Mechanical Ventilation: In severe cases, noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) can help re-expand the lung.

Complications

If not promptly recognized and managed, atelectasis can lead to complications, such as:

- Pneumonia: Stagnant secretions in collapsed lung tissue provide a fertile environment for infection.

- Hypoxemia: Severe collapse impairs oxygenation of blood.

- Respiratory Failure: In extreme cases, especially in patients with limited respiratory reserve.

- Bronchiectasis and Fibrosis: Chronic or unresolved atelectasis may lead to permanent lung damage.

Prognosis

The outcome of atelectasis depends on its cause, size, and rapidity of intervention. In most cases, especially when recognized early and managed appropriately, atelectasis is reversible without long-term effects. However, severe or chronic atelectasis can cause lasting respiratory problems and increased risk of infections.

Prevention

Preventive strategies are vital, particularly for individuals at increased risk:

- Encourage deep breathing and coughing postoperatively and after prolonged bed rest.

- Early mobilization and ambulation.

- Use of incentive spirometry to promote lung expansion.

- Regular chest physiotherapy where indicated.

- Adequate hydration to keep secretions thin and easier to clear.

- Smoking cessation to improve overall lung health.

Nursing Care of Patients with Atelectasis

Nursing Interventions

Promote Airway Clearance

- Encourage deep breathing exercises and use of incentive spirometer every 1-2 hours

- Teach and assist with effective coughing techniques

- Administer prescribed bronchodilators and mucolytics as indicated

- Provide chest physiotherapy, including percussion and postural drainage, if ordered

Optimise Positioning

- Position patient in semi-Fowler’s or upright position to facilitate lung expansion

- Encourage frequent position changes to prevent pooling of secretions and enhance aeration

Maintain Oxygenation

- Administer supplemental oxygen as prescribed

- Monitor oxygen saturation continuously

- Ensure humidification of oxygen to prevent drying of airways

Pain Management

- Assess pain using standard scales and provide analgesics as prescribed

- Implement non-pharmacological pain relief measures, such as relaxation techniques

- Support patient during coughing and deep breathing to reduce discomfort

Monitor for Complications

- Watch for signs of infection (fever, increased sputum, change in sputum colour)

- Report sudden deterioration, increased respiratory distress, or chest pain to the physician promptly

Patient Education

- Explain the importance of deep breathing, coughing exercises, and mobilisation

- Educate about risk factors such as smoking and immobility

- Encourage adherence to prescribed therapies and follow-up appointments

Special Considerations

- For post-operative patients, initiate early ambulation and breathing exercises as soon as feasible

- In elderly or debilitated patients, ensure adequate nutrition and hydration to support recovery

- For paediatric patients, use age-appropriate techniques and engage family members in care

REFERENCES

- Chapter 13. Pulmonary Pathology. In: Kemp WL, Burns DK, Brown TG. eds. Pathology: The Big Picture. McGraw Hill; 2008.

- Ferri FF. Atelectasis. In: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2024. Elsevier; 2024. https://www.clinicalkey.com.

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Chest Physical Therapy. https://www.cff.org/managing-cf/chest-physical-therapy.

- Merck Manuals. Atelectasis https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/bronchiectasis-and-atelectasis/atelectasis.

- Goldman L, et al., eds. Bronchiectasis, atelectasis, and cavitary or cystic lung diseases. In: Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Elsevier; 2024. https://www.clinicalkey.com.

- Kavanagh BP. Respiratory physiology and pathophysiology. In: Miller’s Anesthesia. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com.

- Understanding mucus in your lungs. American Lung Association. https://www.lung.org/blog/lungs-mucus.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.