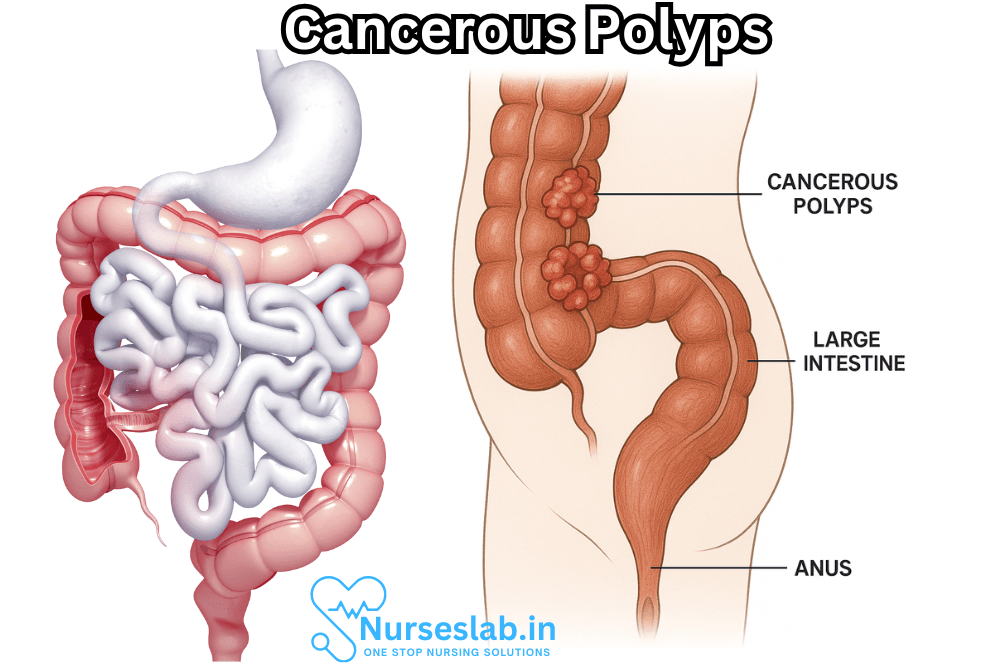

Cancerous polyps, though often silent in their early stages, represent an important aspect of cancer prevention and early intervention—particularly within the gastrointestinal tract. These abnormal tissue growths, found most commonly in the colon and rectum, can transition from harmless to deadly if left unchecked. Understanding the nature, risk factors, detection methods, and management of cancerous polyps is critical for clinicians and patients alike.

What Are Polyps?

Polyps are abnormal growths that arise from the mucous membranes of organs such as the colon, stomach, nose, or uterus. They vary in size, shape, and histological features. While most polyps are benign (non-cancerous), some carry the potential to become malignant (cancerous) over time. The process by which a polyp transforms into cancer is gradual, often taking years, which presents a valuable opportunity for early detection and intervention.

Types of Polyps

- Hyperplastic Polyps: These are typically small, benign, and rarely progress to cancer.

- Adenomatous Polyps (Adenomas): These are the most common precancerous polyps. While not all adenomas become cancerous, most colon cancers begin as adenomatous polyps.

- Serrated Polyps: These can be either benign or have malignant potential, depending on their size and location. Some serrated polyps, especially those in the proximal colon, have a significant risk of becoming cancerous.

- Inflammatory Polyps: Usually associated with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, these polyps themselves are generally not cancerous but indicate an increased risk due to the underlying disease.

The Path from Polyp to Cancer

Cancerous polyps develop through a series of cellular changes. The most common pathway is known as the “adenoma-carcinoma sequence.” Initially, normal cells in the lining of an organ (e.g., the colon) begin to proliferate abnormally, leading to polyp formation. Over time, genetic mutations accumulate, and some polyps may acquire the ability to invade surrounding tissues, eventually becoming malignant.

Risk Factors for Cancerous Polyps

Several factors can increase a person’s risk of developing polyps with malignant potential:

- Age: The risk of polyps and colorectal cancer rises significantly after age 50.

- Family History: Having close relatives with polyps or colorectal cancer increases risk.

- Genetic Syndromes: Conditions such as Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and Lynch syndrome sharply elevate polyp and cancer risk.

- Diet: Diets high in red or processed meats and low in fiber are associated with increased risk.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Chronic inflammation from conditions like ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease raises the likelihood of malignant transformation.

- Lifestyle: Smoking, heavy alcohol use, obesity, and physical inactivity are also contributing factors.

Symptoms and Detection

Polyps, especially in their early stages, often produce no symptoms. As they grow larger or become cancerous, possible symptoms include:

- Rectal bleeding or blood in the stool

- Change in bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation, or stool narrowing lasting more than a few days)

- Abdominal pain or cramping

- Iron deficiency anemia (from chronic blood loss)

- Unexplained weight loss (in advanced disease)

However, most polyps are discovered incidentally during routine screening procedures before symptoms appear.

Screening and Diagnosis

The goal of screening is to identify and remove polyps before they become cancerous. Key screening methods include:

- Colonoscopy: Considered the gold standard, colonoscopy allows direct visualization and removal of polyps throughout the colon.

- Flexible Sigmoidoscopy: Examines the rectum and lower colon.

- Stool Tests: These detect occult (hidden) blood or abnormal DNA shed by polyps or cancers.

- CT Colonography: Also known as virtual colonoscopy, this imaging test provides detailed images of the colon and rectum.

If a polyp is detected, it is typically removed (polypectomy) and sent for histological examination to determine if cancer is present.

Histological Features of Cancerous Polyps

The microscopic examination of a removed polyp reveals its nature. Cancerous polyps may show:

- Invasion of malignant cells into the submucosal or deeper layers

- Irregular, uncontrolled growth patterns

- Cellular atypia (abnormal cell shape and size)

- Mitotic figures (cells actively dividing)

A polyp is considered cancerous (malignant) if cancer cells have broken through the muscularis mucosae, the thin muscle layer separating the mucosa from the submucosa.

Management of Cancerous Polyps

The management of a cancerous polyp depends on several factors, including:

- The type and size of the polyp

- The extent and depth of cancer invasion

- The presence or absence of high-risk features (such as lymphovascular invasion or poor differentiation)

- Margins of resection (whether the entire polyp was removed)

In many cases, complete removal of a cancerous polyp during colonoscopy may be curative if the cancer is confined to the polyp and has not invaded deeply. However, additional surgery and staging may be recommended if there are concerns about incomplete removal or high-risk features.

Follow-up and Surveillance

Patients who have had cancerous polyps must undergo regular follow-up to detect new polyps or recurrence of cancer. Surveillance intervals depend on the number, size, and histological type of previous polyps, as well as patient risk factors.

Prevention Strategies

While some risk factors, such as age and genetics, cannot be changed, several lifestyle modifications can reduce the risk of developing cancerous polyps:

- Eating a high-fiber diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains

- Limiting red and processed meats

- Regular physical activity

- Maintaining a healthy weight

- Avoiding tobacco and excessive alcohol consumption

- Staying up-to-date with recommended screening tests

People with a strong family history or genetic predispositions may benefit from earlier and more frequent screening.

Polyps Beyond the Colon

While colon polyps are the best known due to their association with colorectal cancer, polyps can develop in other organs:

- Stomach: Gastric polyps may occasionally become cancerous, particularly adenomas and certain types of fundic gland polyps.

- Uterus: Endometrial polyps can rarely be cancerous, especially in postmenopausal individuals or those with abnormal bleeding.

- Nasal and Sinus Polyps: Almost always benign, though exceptional cases of malignancy can occur.

The principles of surveillance and management in these organs are similar: early detection and removal are key to preventing malignant transformation.

Prognosis

The prognosis for individuals with cancerous polyps varies:

- If detected early and completely removed, the outlook is generally excellent, with high cure rates.

- If cancer has spread beyond the polyp, prognosis depends on stage at diagnosis, patient health, and response to treatment.

- Regular surveillance is essential to ensure early detection of any recurrence or new polyp formation.

Nursing Care of a Patient With Cancerous Polyps

Nurses play a critical role in the continuum of cancer care, from screening and early detection to treatment, recovery, and ongoing support. This document explores in detail the nursing responsibilities, assessment considerations, interventions, patient education, and holistic support strategies essential for providing quality care to patients diagnosed with cancerous polyps.

Nursing Assessment

Comprehensive assessment is vital in tailoring nursing interventions to the specific needs of the cancer patient.

- Health History and Risk Assessment: Gather information on personal and family history of polyps or cancer, lifestyle factors (diet, smoking, alcohol), genetic predispositions (such as Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis), previous screening results, and presenting symptoms (bleeding, pain, changes in bowel habits).

- Physical Examination: Monitor for signs such as abdominal tenderness, palpable masses, rectal bleeding, unexplained weight loss, and signs of anemia.

- Psychosocial Assessment: Assess the patient’s emotional response to the diagnosis, support systems, coping mechanisms, and potential anxiety or depression.

Preoperative Nursing Care

If surgical intervention is planned, preparing the patient physically and emotionally is crucial.

- Patient Education: Explain the surgical procedure, potential risks, post-operative expectations, and recovery process. Clarify doubts and allay fears, using language the patient understands.

- Consent and Preoperative Preparation: Ensure informed consent is obtained. Complete preoperative checklists, including fasting, pre-surgical medications, and bowel preparation if needed.

- Baseline Data Collection: Record vital signs, weight, laboratory results, and medication history for reference during the post-operative period.

- Psychological Support: Encourage expression of feelings, provide reassurance, and facilitate involvement of family or caregivers as appropriate.

Postoperative Nursing Care

Immediate Postoperative Care

- Monitoring Vital Signs and Surgical Site: Vigilantly monitor vital signs, observe for signs of bleeding or infection, and assess the surgical site for integrity and healing.

- Pain Management: Assess pain using standardized scales and administer analgesics as prescribed. Employ non-pharmacological interventions such as positioning and relaxation techniques.

- Prevention of Complications: Monitor for post-operative complications such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, wound dehiscence, infection, and bowel obstruction. Implement interventions such as early ambulation, leg exercises, and respiratory care.

- Nutritional Support: Initiate gradual reintroduction of oral intake as tolerated. Monitor for nausea, vomiting, or intolerance to feeds. Collaborate with dietitians for individualized nutritional plans.

- Fluid and Electrolyte Balance: Observe intake and output meticulously. Administer IV fluids as prescribed and monitor for signs of dehydration or electrolyte imbalances.

Ongoing/Long-Term Care

- Wound Care: Educate patient and caregivers on wound care techniques, signs of infection, and when to seek medical attention.

- Monitoring for Recurrence: Assist with scheduling and preparing the patient for follow-up colonoscopies or imaging studies. Educate on the importance of routine surveillance to detect recurrence early.

- Medication Administration: Ensure adherence to prescribed medications, including chemotherapy, pain relievers, antiemetics, or antibiotics. Educate on potential side effects and management strategies.

- Management of Ostomies (if applicable): Provide education and support for patients with ostomies, including stoma care, appliance management, psychosocial adaptation, and connection to support groups.

Psychosocial and Emotional Support

Cancer diagnoses profoundly impact patients and their families. Nurses are instrumental in providing emotional, psychological, and social support.

- Emotional Counseling: Offer listening, reassurance, and empathetic communication. Address fears of recurrence, mortality, and changes in body image.

- Facilitation of Communication: Encourage open communication between the patient, family, and healthcare team, empowering patients to participate in decision-making.

- Referral to Support Services: Connect patients with counseling services, social workers, financial advisors, and cancer support groups as needed.

- Cultural and Spiritual Sensitivity: Respect cultural beliefs and spiritual needs. Collaborate with chaplaincy or spiritual care providers if the patient desires.

Patient and Family Education

Education enhances self-management, improves outcomes, and reduces anxiety.

- Understanding the Diagnosis: Provide clear information about cancerous polyps, treatment options, expected outcomes, and possible side effects.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Advise on healthy eating, regular exercise, smoking cessation, limiting alcohol, and stress management to optimize recovery and reduce recurrence risk.

- Medication and Treatment Adherence: Emphasize the importance of following prescribed treatment regimens and attending all follow-up appointments.

- Recognizing Warning Signs: Teach patients what symptoms should prompt immediate medical attention, such as severe pain, persistent vomiting, fever, or rectal bleeding.

Coordination of Care and Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Optimal care of patients with cancerous polyps requires a team approach.

- Collaboration: Work closely with physicians, surgeons, oncologists, dietitians, pharmacists, psychologists, and social workers to formulate and execute individualized care plans.

- Continuity of Care: Ensure smooth transitions between inpatient, outpatient, and home care settings. Provide thorough handovers and clear documentation.

- Advocacy: Serve as a patient advocate, ensuring needs are met, preferences are respected, and informed choices are facilitated throughout the course of care.

Special Considerations for Vulnerable Populations

Elderly patients, those with disabilities, or individuals lacking strong support systems may require additional attention.

- Individualized Assessment: Tailor assessments and interventions based on age, comorbidities, cognitive status, and functional ability.

- Community Resources: Assist with accessing home health nursing, meal delivery services, transportation, and other community-based resources.

Ethical and Legal Aspects

Nurses must navigate complex ethical and legal considerations in cancer care.

- Informed Consent: Verify that the patient comprehends the nature of their illness, treatment options, and likely outcomes before proceeding with interventions.

- Confidentiality: Safeguard patient privacy in accordance with legal standards and professional codes of conduct.

- Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Recognize when to shift goals from curative to comfort-focused care and support patients and families through these transitions.

REFERENCES

- Alkilani YG, Apodaca-Ramos I. Cervical Polyps. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562185/. [Updated 9 Sept 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Understanding Polyps and Their Treatment. https://www.asge.org/home/for-patients/patient-information/understanding-polyps.

- Ejtehadi F, Taghavi AR, Ejtehadi F, et al. Prevalence of colonic polyps detected by colonoscopy in symptomatic patients and comparison between different age groups. What age should be considered for investigation? Pol Przegl Chir. 2023;96(1):15-21. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0053.3997

- Arteaga CD, Wadhwa R. Gastric Polyphttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560704/. [Updated 18 July 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Cancer Council. Cancer Information: Polyps. https://www.cancer.org.au/polyps.

- Jones V. Cancer in the sigmoid colon: what it means when colon cancer is on the left side. MD Anderson Cancer Center. February 14, 2024.

- Mansour T, Chowdhury YS. Endometrial Polyp. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557824/. [Updated 14 Dec 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Sninsky JA, Shore BM, Lupu GV, Crockett SD. Risk factors for colorectal polyps and cancer. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 2022;32(2):195-213. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2021.12.008

- Meseeha M, Attia M. Colon Polyps. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430761/. [Updated 15 Aug 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.