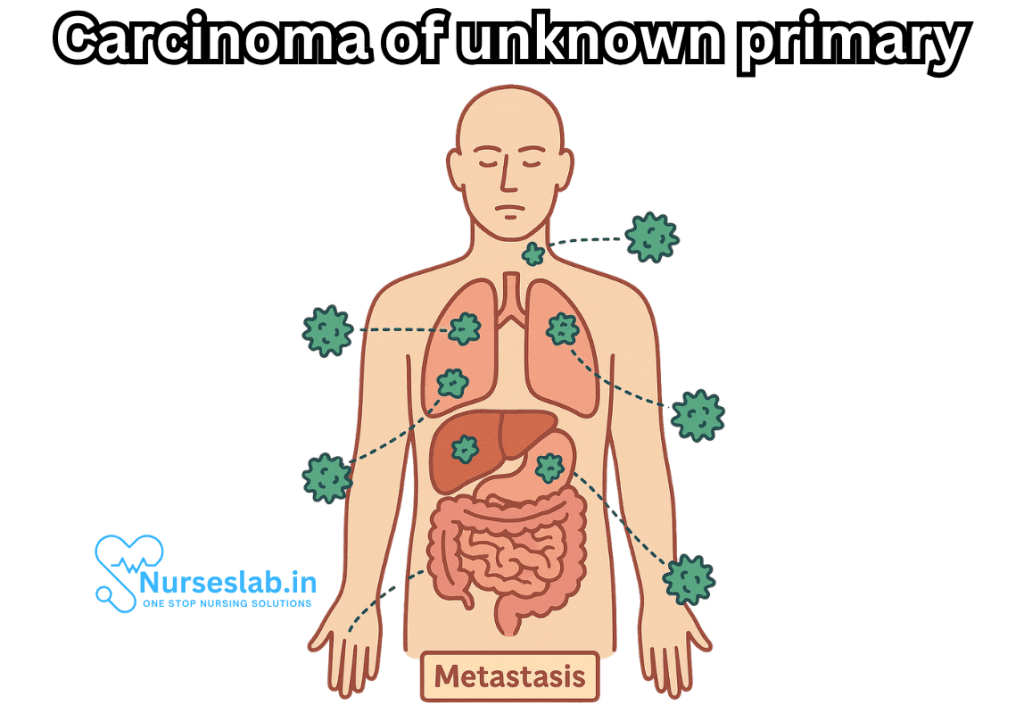

Carcinoma of unknown primary (CUP) represents one of the most enigmatic and perplexing challenges in the field of oncology. It describes a group of cancers that are identified by the presence of metastatic tumors cancer that has spread to other parts of the body without an obvious origin or primary tumor site after thorough clinical and diagnostic evaluation. Though relatively rare, CUP is significant because it accounts for roughly 2-5% of all cancer diagnoses, presents uniquely in its clinical course, and often requires a nuanced and multidisciplinary approach for optimal patient management.

What is Carcinoma of Unknown Primary?

Carcinoma of unknown primary is not a single disease, but rather a heterogeneous group of metastatic epithelial malignancies. The unifying feature is, as the name suggests, the inability to identify the primary site of origin despite comprehensive workup that usually includes a detailed medical history, physical examination, laboratory analyses, imaging studies, and histopathological evaluation.

In CUP, patients typically present with symptoms attributable to metastatic disease—such as enlarged lymph nodes, pain, weight loss, or organ dysfunction—while the initial or primary tumor remains elusive. The lack of an identifiable primary tumor poses significant challenges for both prognosis and treatment, as many cancer therapies are designed specifically for tumor types originating from particular organs.

Epidemiology and Demographics

CUP most frequently affects adults, with a median age at diagnosis around 60 years. It is slightly more common in males compared to females. The precise incidence varies geographically and is influenced by access to advanced diagnostic tools and the thoroughness of the evaluation process. Despite advances in imaging and molecular diagnostics, a significant minority of metastatic cancers still fall into the CUP category each year.

Pathogenesis and Theories

The mechanisms underlying CUP remain under investigation. Several hypotheses have been proposed:

- Early Metastasis Hypothesis: Suggests that some cancers may have a biological propensity for early metastasis, spreading before the primary tumor becomes clinically detectable or before it grows large enough to be identified.

- Regressed Primary Tumor Hypothesis: In some cases, the primary tumor may have regressed or been destroyed (e.g., by the immune system), leaving only the metastatic deposits behind.

- Unique Biology Hypothesis: Proposes that CUP may have distinct molecular characteristics that set it apart from other metastatic cancers, making it difficult to classify using conventional techniques.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with CUP typically present with nonspecific symptoms related to the metastatic spread. Common presentations include:

- Enlarged, painless lymph nodes (cervical, axillary, or inguinal)

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fatigue and malaise

- Pain, depending on the sites of metastases (bone, liver, lung, etc.)

- Jaundice or ascites, if the abdominal organs are involved

- Respiratory symptoms (cough, dyspnea) if there is lung involvement

The metastases are most often found in lymph nodes, liver, lungs, bones, or peritoneum. In some cases, a single site is involved, while in others, multiple organ systems may be affected.

Diagnostic Approach

The diagnosis of CUP is made after an exhaustive search for the primary tumor fails to reveal its site. The diagnostic workup typically includes:

- Comprehensive History and Physical Examination: To identify any potential primary site based on symptoms, risk factors, and family history.

- Laboratory Tests: Including complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, tumor markers (e.g., CEA, CA 19-9, CA 125, PSA in men), and others as indicated.

- Imaging Studies:

- CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are standard.

- PET-CT scans can be helpful in identifying hypermetabolic activity suggestive of a primary tumor.

- Mammography in women, especially if there is axillary lymphadenopathy.

- Targeted imaging such as MRI or ultrasound based on specific findings.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry: Biopsy of the metastatic lesion is mandatory. Immunohistochemical staining can help identify the tissue of origin by detecting specific markers characteristic of certain cancer types.

Molecular and Genomic Profiling: Advanced techniques, such as gene expression profiling or next-generation sequencing, may provide clues to the likely site of origin in some cases.

Despite these efforts, in a substantial number of cases, the primary tumor remains undetectable.

Classification of CUP

CUP is broadly classified based on the histological subtype of the metastatic cancer:

- Adenocarcinoma: The most common type, representing about 60% of CUP cases.

- Poorly Differentiated Carcinoma/Undifferentiated Carcinoma: About 30%.

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Around 5%.

- Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: Around 1%.

- Others: Rare variants or mixed histologies.

Prognostic Subsets

Although CUP generally carries a poor prognosis, it is not a monolithic disease. Patients are classified into “favorable” and “unfavorable” prognostic subsets based on clinical and pathological features. About 15-20% of CUP patients fall into favorable subsets and may benefit from site-specific therapy with outcomes similar to those of known primary cancers. Examples include:

- Women with isolated axillary lymph node metastases: Often treated as breast cancer.

- Squamous cell carcinoma involving cervical lymph nodes: Managed similarly to head and neck cancers.

- Peritoneal carcinomatosis in women: Treated as ovarian cancer.

- Men with blastic bone metastases and elevated PSA: Treated as prostate cancer.

The remaining majority—those in the unfavorable subset—have disseminated disease and a poor prognosis, with median survival measured in months.

Treatment Strategies

The management of CUP is individualized and often involves a multidisciplinary team of oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, and surgeons. The main treatment modalities include:

Site-Specific Therapy

When the likely primary site can be inferred, treatment is guided accordingly. For example, women with isolated axillary lymph node metastases may receive breast cancer protocols, or men with bone metastases and elevated PSA may get prostate cancer-directed therapy.

Empiric Chemotherapy

For most patients, especially those in the unfavorable subset, empiric chemotherapy regimens are used. These often include platinum-based doublet therapies (such as carboplatin plus paclitaxel, or cisplatin plus gemcitabine). The choice of regimen is based on patient factors (age, performance status, comorbidities) and cancer histology.

Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

As molecular profiling becomes more accessible, targeted therapies may be considered when actionable mutations or biomarkers are identified (e.g., EGFR, ALK, NTRK). Immunotherapy has shown promise in selected cases, particularly those with high microsatellite instability or high tumor mutational burden.

Palliative Care

Given the aggressive nature and advanced stage at diagnosis for most CUP cases, symptom management and quality of life are of paramount importance. Palliative care—addressing pain, nutritional needs, psychological support, and end-of-life care—should be integrated early into the treatment plan.

Nursing Care for Patients with Carcinoma of Unknown Primary (CUP)

Nurses play a critical role in supporting patients with CUP, providing not only physical care but also emotional, informational, and advocacy support. This document outlines essential aspects and strategies for the nursing care of patients diagnosed with Carcinoma of Unknown Primary.

Nursing Assessment and Diagnosis

Comprehensive Assessment

- History Taking: Elicit a thorough medical history, including previous illnesses, family history of cancer, symptoms, and risk factors (e.g., smoking, occupational exposures).

- Symptom Assessment: Document symptoms such as unexplained weight loss, pain, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, or site-specific complaints (e.g., cough, neurological deficits, jaundice).

- Physical Examination: Conduct a head-to-toe assessment to detect abnormal masses, organomegaly, lymph node enlargement, or other signs of metastasis.

- Psycho-social Evaluation: Assess the patient’s psychological state, anxiety levels, coping mechanisms, support systems, and informational needs.

Common Nursing Diagnoses

- Acute pain related to tumor burden or metastasis

- Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

- Fatigue related to disease process or treatment

- Disturbed body image related to physical changes or treatment side effects

- Anxiety and fear related to diagnosis, prognosis, and uncertainty

- Deficient knowledge regarding disease process and treatment options

Planning and Goals of Nursing Care

The goals for the nursing care of patients with CUP are rooted in maintaining quality of life, alleviating symptoms, providing psychosocial support, and helping patients navigate the uncertainties associated with the diagnosis.

- Relieve pain and manage other distressing symptoms

- Improve nutritional status and prevent complications of malnutrition

- Reduce anxiety and depression through counseling and education

- Promote patient and family understanding of disease and treatment

- Support coping and adaptation to chronic illness and uncertainty

- Coordinate multidisciplinary care and advocate for patient needs

Interventions and Nursing Actions

Pain and Symptom Management

- Pain Control: Administer analgesics as prescribed, using the WHO pain ladder as a guide. Monitor effectiveness and side effects. Utilize both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods (e.g., relaxation, heat/cold therapy).

- Management of Other Symptoms: Address symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, constipation, or neurological deficits with appropriate interventions (antiemetics, laxatives, breathing support, etc.).

- Monitor for Complications: Regularly assess for complications such as infections, deep vein thrombosis, or organ dysfunction, which may occur due to advanced disease or immunosuppression.

Nutritional Support

- Encourage small, frequent, high-calorie meals and snacks to address poor appetite and weight loss.

- Collaborate with dietitians to create individualized meal plans.

- Monitor weight, body mass index, and laboratory markers of nutrition (albumin, prealbumin).

- Consider nutritional supplements or enteral feeding if oral intake is insufficient.

Psychological and Emotional Support

- Provide a listening ear and empathetic presence; allow the patient and family to express fears and concerns.

- Offer counseling or refer to mental health professionals as needed.

- Facilitate support groups or connect patients with others experiencing CUP or advanced cancer.

- Encourage the involvement of family and significant others in care and decision-making.

Education and Communication

- Educate the patient and family about the nature of CUP, the diagnostic process, prognosis, and available treatment options (e.g., empirical chemotherapy, targeted therapy, palliative care).

- Provide information in clear, understandable language; use written materials and visual aids when appropriate.

- Clarify misconceptions and answer questions honestly. Be transparent about uncertainties and possible outcomes.

- Facilitate communication between the patient, family, and members of the healthcare team.

End-of-Life Care and Palliative Support

- Introduce palliative care early to manage symptoms and improve quality of life, regardless of prognosis.

- Discuss advance care planning, goals of care, and patient wishes regarding life-sustaining treatment.

- Support spiritual and cultural needs; involve chaplaincy or other resources as desired by the patient.

- Assist with hospice referrals when appropriate and provide bereavement support to families.

Coordination of Care

- Act as a patient advocate, ensuring access to necessary tests, treatments, and support services.

- Foster collaboration among physicians, pharmacists, dietitians, social workers, and other team members.

- Help navigate healthcare systems, appointments, and financial or insurance concerns.

Challenges in Nursing Care for CUP

- Diagnostic Uncertainty: The inability to identify the primary tumor may cause frustration and anxiety for patients and families, as well as difficulties in choosing the most effective treatment.

- Prognostic Ambiguity: Prognosis is often uncertain, which complicates care planning and communication.

- Symptom Burden: Advanced metastatic disease frequently results in a high symptom burden, necessitating vigilant assessment and proactive management.

- Psychosocial Distress: Patients with CUP often report higher levels of psychological distress due to uncertainty, fear of the unknown, and feeling excluded from standard cancer care pathways.

- Resource Limitations: Access to specialized care, diagnostic tests, or novel therapies may be limited for some patients, requiring creative problem-solving and advocacy by the nurse.

Cultural and Ethical Considerations

- Be sensitive to cultural beliefs and practices regarding illness, cancer, and death. Tailor education and support to individual backgrounds.

- Respect patient autonomy and wishes regarding the extent of information and involvement in decision-making.

- Address ethical dilemmas such as treatment futility, quality of life versus length of life, and participation in clinical trials.

Family and Caregiver Support

- Educate family members about the disease, expected course, and how they can assist in care.

- Assess caregiver stress and provide resources for respite care or support services.

- Encourage open communication between the patient, family, and healthcare team.

- Prepare families for potential changes in patient condition and for end-of-life decisions.

Documentation and Ongoing Evaluation

Nurses must maintain meticulous documentation of assessments, interventions, patient responses, and communications. Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of care plans, adjusting as necessary based on patient needs, progression of disease, and family input.

REFERENCES

- Alshareeda AT, Al-Sowayan BS, Alkharji RR, et al. Cancer of Unknown Primary Site: Real Entity or Misdiagnosed Disease?. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32328196/ J Cancer. 2020 Apr 6;11(13):3919-3931.

- DeVita VT Jr, et al., eds. Cancer of unknown primary. In: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 12th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2023.

- Laprovitera N, Riefolo M, Ambrosini E, et al. Cancer of Unknown Primary: Challenges and Progress in Clinical Management. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7866161/. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Jan 25;13(3):451.

- Carcinoma of unknown primary treatment (PDQ) – Patient version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/unknown-primary/patient/unknown-primary-treatment-pdq.

- Niederhuber JE, et al., eds. Carcinoma of unknown primary. In: Abeloff’s Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com.

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Cancer of Unknown Primary (CUP) Treatment. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26389252/(PDQ

®): Health Professional Version. 2024 May 6. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.