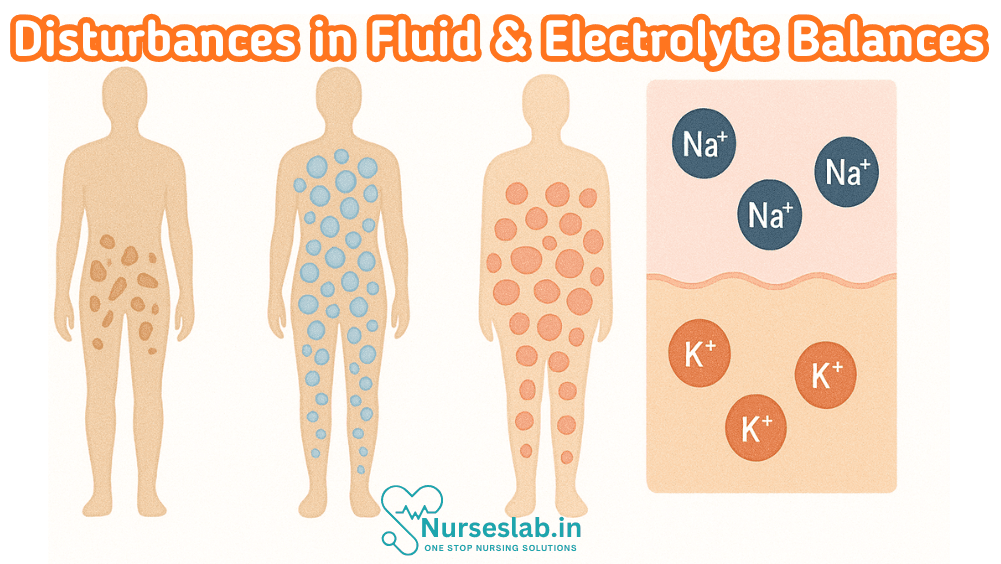

Explore fluid and electrolyte disturbances: from dehydration and edema to sodium, potassium, and acid-base imbalances. These conditions impact cardiac, renal, and neurological function—critical in acute care, chronic disease management, and nursing interventions for safe, effective treatment

Introduction

Fluid and electrolyte balance is fundamental to the maintenance of health and optimal functioning in all individuals. In nursing practice, understanding the disturbances of this delicate equilibrium is essential for delivering safe, effective, and evidence-based care. Pathological alterations in fluid and electrolyte status may arise from a multitude of causes, including acute illness, chronic diseases, genetic disorders, pharmacological influences, and surgical interventions. The integration of genetic insights into nursing assessment and intervention strategies is increasingly relevant, as inherited disorders and genetic predispositions can profoundly affect fluid and electrolyte homeostasis.

Physiology of Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

Body Water Compartments

The human body comprises approximately 50–70% water, distributed across two main compartments: intracellular fluid (ICF) and extracellular fluid (ECF). The ICF, contained within cells, accounts for about two-thirds of total body water, while the ECF—which includes interstitial fluid, plasma, and transcellular fluids—makes up the remaining third. Maintenance of the correct volume and composition of these compartments is critical, as even small deviations can disrupt cellular function and lead to clinical manifestations.

Major Electrolytes and Their Functions

- Sodium (Na+): Chief cation of ECF; regulates fluid balance, nerve conduction, and muscle contraction.

- Potassium (K+): Main cation of ICF; essential for cardiac and neuromuscular activity.

- Calcium (Ca2+): Important for bone health, blood clotting, and neuromuscular transmission.

- Chloride (Cl-): Principal anion of ECF; maintains osmotic pressure and acid-base balance.

- Magnesium (Mg2+): Required for enzyme activity, neuromuscular function, and cardiac stability.

- Phosphate (PO43-): Key role in energy metabolism and bone structure.

Mechanisms of Homeostasis

Homeostasis is maintained through complex interactions involving the kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, endocrine system, and cellular membranes. The kidneys play a central role, regulating water and electrolyte excretion according to physiological needs. Hormonal control—particularly by antidiuretic hormone (ADH), aldosterone, and parathyroid hormone (PTH)—modulates absorption, secretion, and redistribution of electrolytes. Thirst and dietary intake also contribute to the maintenance of balance.

Pathology of Fluid Imbalances

Types of Fluid Imbalances

- Dehydration: Deficit of body water, commonly resulting from excessive fluid loss or inadequate intake.

- Overhydration (Fluid overload): Excessive accumulation of body water, often due to impaired renal excretion or excessive intravenous fluids.

Causes and Pathophysiology

- Dehydration: Causes include vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, excessive sweating, burns, and reduced oral intake. Pathophysiologically, dehydration leads to increased serum osmolality, reduced tissue perfusion, and cellular dysfunction.

- Overhydration: May result from heart failure, renal impairment, SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion), or excessive intravenous fluid administration. The resultant dilution of plasma electrolytes can precipitate hyponatraemia and cellular oedema.

Clinical Signs

- Dehydration: Thirst, dry mucous membranes, reduced skin turgor, tachycardia, hypotension, confusion, oliguria.

- Overhydration: Peripheral oedema, pulmonary congestion, elevated jugular venous pressure, hypertension, weight gain.

Pathology of Electrolyte Imbalances

Common Disturbances, Causes, and Effects

- Hyponatraemia (Low sodium): Causes include SIADH, diarrhoea, vomiting, heart failure, renal disease; symptoms range from headache and confusion to seizures and coma.

- Hypernatraemia (High sodium): Often due to water deficit or excessive sodium intake; presents with irritability, lethargy, muscle twitching, and, in severe cases, neurological impairment.

- Hypokalaemia (Low potassium): Arises from diuretic therapy, vomiting, diarrhoea, or renal loss; manifests as muscle weakness, arrhythmias, and constipation.

- Hyperkalaemia (High potassium): Usually caused by renal failure, acidosis, or excessive potassium intake; can cause cardiac conduction disturbances, muscle paralysis, and cardiac arrest.

- Hypocalcaemia (Low calcium): Linked to vitamin D deficiency, hypoparathyroidism, or renal disease; symptoms include tetany, paraesthesia, muscle cramps, and cardiac arrhythmias.

- Hypercalcaemia (High calcium): Often secondary to hyperparathyroidism or malignancy; presents with polyuria, constipation, nausea, confusion, and cardiac arrhythmias.

- Other disturbances: Imbalances of magnesium, phosphate, and chloride can also lead to significant clinical problems, such as neuromuscular irritability, metabolic bone disease, and acid-base disturbances.

Genetic Factors in Fluid and Electrolyte Disturbances

Inherited Disorders

- Cystic Fibrosis: Autosomal recessive disorder affecting the CFTR gene, leading to abnormal chloride and sodium transport across epithelial cells. This results in viscous secretions, dehydration, and electrolyte loss, particularly in sweat and respiratory secretions.

- Bartter Syndrome: Group of rare inherited renal tubular disorders characterised by impaired sodium and chloride reabsorption, resulting in hypokalaemia, metabolic alkalosis, and increased urine output.

- Gitelman Syndrome: Similar to Bartter syndrome, but with distinctive hypomagnesaemia and hypocalciuria.

- Liddle Syndrome: Genetic mutation resulting in increased sodium reabsorption in the distal nephron, leading to hypertension and hypokalaemia.

- Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: Enzyme defects affecting steroid synthesis, impacting sodium and potassium balance through altered aldosterone production.

Genetic Predispositions and Molecular Mechanisms

Genetic variants in genes encoding ion channels, transporters, and hormonal receptors can influence individual susceptibility to fluid and electrolyte disturbances. For example, polymorphisms in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) may predispose patients to hypertension and sodium retention. Advances in molecular genetics have enabled the identification of mutations responsible for inherited disorders, facilitating targeted interventions and genetic counselling.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical presentation of fluid and electrolyte imbalances varies according to the specific disturbance, its severity, and the underlying cause. Common symptoms include confusion, muscle cramps, weakness, fatigue, palpitations, oedema, and changes in urine output. Severe imbalances can lead to life-threatening complications such as seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, and coma.

Laboratory Investigations

- Serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, phosphate)

- Renal function tests (urea, creatinine)

- Arterial blood gases (for acid-base assessment)

- Urine analysis (osmolality, electrolyte excretion)

- Genetic testing (for suspected inherited disorders)

Differential Diagnosis

Nurses must consider various differential diagnoses when evaluating fluid and electrolyte disturbances, including acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, endocrine disorders (such as diabetes insipidus and SIADH), gastrointestinal losses, medication effects, and genetic syndromes. A thorough history, clinical examination, and targeted investigations are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Management Strategies

Medical Management

- Dehydration: Oral or intravenous fluid replacement, correction of underlying cause.

- Overhydration: Fluid restriction, diuretics, management of underlying cardiac or renal pathology.

- Electrolyte disturbances: Careful replacement or restriction of specific electrolytes, guided by laboratory values and clinical status.

Pharmacological Interventions

- Loop diuretics (for hypervolaemia, hypercalcaemia)

- Potassium-sparing diuretics (for hypokalaemia)

- Electrolyte supplements (oral or intravenous sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium)

- Hormonal therapy (e.g., desmopressin for diabetes insipidus, fludrocortisone for adrenal insufficiency)

Dietary Modifications

- Adjusting sodium, potassium, and fluid intake according to individual needs and underlying pathology

- Ensuring adequate hydration, particularly in vulnerable populations (elderly, children, athletes)

- Education on dietary sources of electrolytes and avoidance of excessive intake

Monitoring

- Regular assessment of vital signs, fluid balance charts, and daily weights

- Frequent laboratory monitoring of serum and urine electrolytes

- Clinical observation for early signs of deterioration

Nursing Considerations

Assessment and Care Planning

Nurses play a pivotal role in the assessment, planning, and evaluation of care for patients with fluid and electrolyte disturbances. Comprehensive assessment should include a detailed history (including medication use, dietary habits, family history of genetic disorders), physical examination, and review of laboratory results. Individualised care plans must address the specific needs, risks, and preferences of each patient.

Patient Education

- Educating patients and families about the importance of maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance

- Instruction on recognising early warning signs (e.g., muscle cramps, confusion, palpitations)

- Guidance on dietary management and medication adherence

- Providing information on genetic counselling for inherited disorders

Monitoring and Documentation

- Accurate documentation of intake and output, daily weights, and clinical observations

- Timely reporting of abnormal findings to the medical team

- Ongoing evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions and adjustment of care plans

Prevention Strategies

- Routine screening for electrolyte disturbances in at-risk populations

- Early intervention for minor imbalances to prevent progression

- Education on risk factors and prevention strategies (e.g., hydration during hot weather, medication review)

Case Studies/Examples

Case 1: Hyponatraemia in the Elderly

Mrs. Martina Peskova , a 72-year-old woman, presents with confusion and lethargy. She has a history of heart failure and is on diuretic therapy. Laboratory investigations reveal marked hyponatraemia. The nursing team assesses her fluid status, reviews her medications, and educates her family about the risks associated with excessive fluid intake. Management includes careful correction of sodium levels and close monitoring for neurological deterioration.

Case 2: Genetic Disorder – Bartter Syndrome

Master Gunj jang, a 10-year-old boy, is admitted with muscle weakness, polyuria, and growth retardation. Genetic testing confirms Bartter syndrome. The nursing team coordinates multidisciplinary care, including electrolyte replacement, dietary modifications, and genetic counselling for the family. Ongoing monitoring and support are provided to optimise his growth and development.

Case 3: Hyperkalaemia Secondary to Renal Failure

Mr. Singh, aged 55, is undergoing dialysis for chronic kidney disease. He develops severe hyperkalaemia, manifesting as palpitations and ECG changes. Nurses promptly recognise the signs, initiate emergency management (including administration of calcium gluconate, insulin, and glucose), and collaborate with the medical team to stabilise his condition. Patient education focuses on dietary potassium restriction and adherence to dialysis schedules.

Conclusion

An in-depth understanding of the pathology and genetics of fluid and electrolyte disturbances is essential for nurses to deliver safe, effective, and compassionate care. By recognising the clinical manifestations, employing appropriate diagnostic tools, and implementing timely management strategies, nurses can mitigate complications and promote optimal patient outcomes. Genetic factors, although less commonly encountered, are increasingly relevant in modern nursing practice and require awareness, assessment, and appropriate referral.

Ultimately, a holistic approach that integrates knowledge of pathophysiology, genetics, and evidence-based nursing interventions will empower nurses to address the complex challenges posed by fluid and electrolyte imbalances across diverse patient populations.

REFERENCES

- Ramadas Nayak, Textbook of Pathology and Genetics for Nurses, 2nd Edition,2024, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-93-5270-031-8.

- Suresh Sharma, Textbook of Pharmacology, Pathology & Genetics for Nurses II, 2nd Edition, 31 August 2022, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-9354655692.

- Kumar, V., Abbas, A.K., & Aster, J.C. (2020). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th Edition. Elsevier.

- McCance, K.L., & Huether, S.E. (2018). Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 8th Edition. Elsevier.

- Ernstmeyer K, Christman E, editors. Nursing Fundamentals [Internet]. Eau Claire (WI): Chippewa Valley Technical College; 2021. Chapter 15 Fluids and Electrolytes. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591820/

- Prabhu, S.R. (2023). Imbalances in Fluids and Electrolytes, Acids and Bases: An Overview. In: Textbook of General Pathology for Dental Students. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31244-1_14

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.