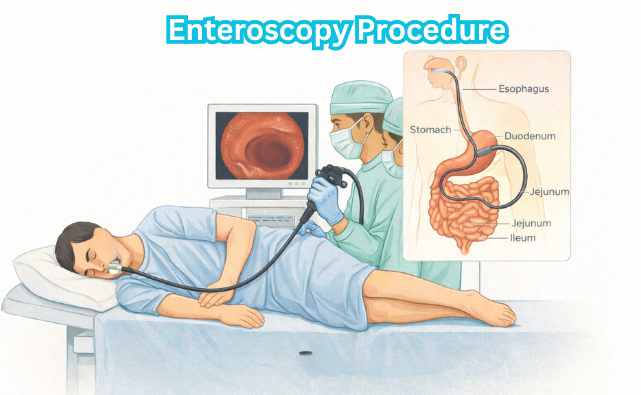

Enteroscopy is a specialized endoscopic procedure that allows direct visualization of the small intestine to diagnose and treat bleeding, inflammation, tumors, and other GI conditions. It offers deeper access than standard endoscopy for accurate evaluation

Introduction

Enteroscopy is a specialised endoscopic procedure designed to visualise, diagnose, and sometimes treat disorders of the small intestine. Unlike gastroscopy and colonoscopy, which primarily assess the stomach and large bowel, respectively, enteroscopy focuses on the segment of the gastrointestinal tract that extends from the duodenum to the ileum.

The small intestine, comprising approximately 6 metres in length in adults, has historically been a challenging area to access due to its length, mobility, and convoluted loops. With advancements in endoscopic technology, enteroscopy has become a vital tool for gastroenterologists, particularly in the diagnosis and management of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, small bowel tumours, Crohn’s disease, and malabsorptive disorders.

Indications for Enteroscopy

The primary indications for enteroscopy are:

- Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB): This refers to bleeding of unknown origin that persists or recurs after upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies have failed to identify a source. OGIB may present as iron-deficiency anaemia, melena, or overt bleeding.

- Suspected small bowel tumours: Such as adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, carcinoid tumours, and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs).

- Small bowel Crohn’s disease: For diagnosis, assessment of extent, and evaluation of complications such as strictures or fistulae.

- Small bowel polyposis syndromes: Including Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

- Unexplained chronic diarrhoea, malabsorption, or weight loss: When other modalities have not yielded a diagnosis.

- Evaluation of abnormal imaging findings: Such as lesions detected on CT or MRI enterography.

Types of Enteroscopy

Several techniques have evolved to facilitate enteroscopic examination, each with unique advantages and limitations. The principal types include:

- Push Enteroscopy

- Balloon-Assisted Enteroscopy (BAE)

- Single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE)

- Double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE)

- Spiral Enteroscopy

- Capsule Endoscopy (for comparison)

Push Enteroscopy

Push enteroscopy utilises a long, flexible endoscope (typically 200 cm) that is advanced through the mouth, past the stomach, and into the proximal jejunum. While limited in depth (usually 60–120 cm beyond the ligament of Treitz), it allows for direct visualisation and therapeutic intervention in the upper small intestine. It is commonly used for evaluating proximal small bowel pathology, particularly when lesions are suspected within reach.

Balloon-Assisted Enteroscopy (BAE)

BAE is the gold standard for deep small bowel evaluation. It relies on overtubes fitted with inflatable balloons that anchor the bowel, allowing the endoscope to pleat the small intestine over itself and achieve deep insertion. There are two main types:

- Double-Balloon Enteroscopy (DBE): Introduced by Yamamoto in 2001, DBE uses two balloons—one at the tip of the endoscope and another on the overtube. By alternately inflating and deflating these balloons, the endoscope can be advanced incrementally through the small bowel, sometimes reaching the ileocaecal valve. Both oral and anal approaches are possible.

- Single-Balloon Enteroscopy (SBE): SBE employs a single balloon on the overtube. While slightly less complex than DBE, it offers similarly deep insertion and diagnostic yield.

Spiral Enteroscopy

Spiral enteroscopy utilises an overtube with a spiral-shaped ridge. By rotating the overtube, the small bowel is pleated onto the endoscope, allowing for relatively rapid advancement. Spiral enteroscopy is efficient and can achieve comparable depths to BAE, though it may be less suitable for therapeutic interventions.

Capsule Endoscopy: A Non-Invasive Alternative

Capsule endoscopy, while not a form of enteroscopy per se, is often used as a first-line investigation for small bowel pathology. A swallowable capsule fitted with a miniature camera transmits images as it traverses the gut. Capsule endoscopy is non-invasive and excellent for detecting mucosal abnormalities, but it does not allow for tissue biopsy or therapeutic intervention. Findings on capsule endoscopy often guide the need for subsequent enteroscopic procedures.

Pre-Procedure Preparation

Proper patient preparation is crucial for the success and safety of enteroscopy.

- Patient Selection: Detailed history and physical examination are essential. Contraindications include severe cardiopulmonary instability, known or suspected bowel perforation, and uncorrected coagulopathy.

- Informed Consent: Patients must be counselled regarding risks, benefits, alternatives (including capsule endoscopy), and potential need for therapy or surgery.

- Fasting: At least 6–8 hours of fasting prior to the procedure is recommended to reduce aspiration risk and ensure a clear visual field.

- Bowel Preparation: For oral approaches, fasting suffices. For anal (retrograde) approaches, a standard colonoscopy bowel preparation is required to clear the distal bowel.

- Medication Review: Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents may need to be withheld or bridged, depending on the indication and risk profile. Diabetic medications may need adjustment.

- Pre-Procedure Investigations: These may include basic blood tests (haemoglobin, renal function, coagulation profile), ECG, and chest X-ray in select patients.

Procedure Technique

The technique varies depending on the type of enteroscopy and the approach (oral or anal).

Patient Positioning and Sedation

Patients are usually positioned in the left lateral decubitus position for oral enteroscopy and in the left lateral or supine position for anal approaches. Conscious sedation with intravenous midazolam and fentanyl is commonly used, although general anaesthesia may be preferred in prolonged or complex cases, especially in paediatric or uncooperative patients.

Oral (Antegrade) Approach

- The endoscope is introduced via the mouth and advanced through the oesophagus, stomach, and duodenum.

- With balloon-assisted techniques, the overtube and balloon(s) are used to anchor and pleat the bowel, allowing incremental advancement.

- Visual inspection is performed as the endoscope is advanced, with careful attention to mucosal abnormalities, vascular lesions, polyps, masses, ulcers, or strictures.

- Therapeutic interventions (such as biopsy, polypectomy, argon plasma coagulation, or control of bleeding) can be performed as indicated.

Anal (Retrograde) Approach

- The endoscope is introduced via the anus and advanced through the colon to the ileocaecal valve.

- After intubation of the terminal ileum, the enteroscope is advanced as far as possible into the distal small bowel.

- Balloon-assisted or spiral techniques are employed as required.

- This approach is particularly useful when a lesion is suspected in the distal ileum or when the oral approach is not feasible.

Fluoroscopy Guidance

Fluoroscopy may be used to monitor the progression of the endoscope, particularly in complex cases or when precise localisation is necessary. This is especially helpful in patients with altered anatomy, such as those with prior bowel surgery.

Procedure Duration and Completion

Enteroscopy can be time-consuming, often lasting 60–120 minutes, and occasionally longer if therapeutic interventions are performed. The procedure is generally concluded when the suspected pathology is identified and managed, or when further advancement is not feasible due to looping, patient discomfort, or anatomical constraints.

Findings and Diagnostic Yield

The diagnostic yield of enteroscopy depends on the indication, technique, and expertise of the endoscopist. Studies show the following yields:

- Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: 60–80%

- Suspected small bowel tumours: 50–70%

- Inflammatory bowel disease: 40–60%

- Polyposis syndromes: High, especially with known polyps on imaging or family history

Common findings include:

- Angioectasias (dilated blood vessels prone to bleeding)

- Ulcers (due to Crohn’s disease, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or infections)

- Tumours (benign or malignant)

- Polyps (hamartomas, adenomas)

- Strictures, fistulae, or mucosal erosions

- Evidence of malabsorption (villous atrophy, lymphangiectasia)

Therapeutic Applications

Beyond diagnosis, enteroscopy allows for a range of therapeutic interventions, including:

- Haemostasis: Injection therapy, argon plasma coagulation, bipolar cautery, or haemoclips for bleeding lesions

- Polypectomy: Removal of small bowel polyps, particularly in polyposis syndromes

- Dilation of strictures: Balloon dilation for Crohn’s disease or post-surgical strictures

- Foreign body retrieval: Removal of retained capsules, bezoars, or ingested objects

- Tissue sampling: Biopsy of suspicious lesions for histopathological evaluation

Complications and Risk Management

Although generally safe, enteroscopy is associated with certain risks:

- Perforation: The risk is higher than with upper or lower endoscopy, especially during therapeutic interventions (0.3–1%).

- Bleeding: Particularly after biopsy or polypectomy.

- Pancreatitis: Rare, usually associated with manipulation near the ampulla of Vater.

- Cardiorespiratory compromise: Due to sedation or vagal stimulation.

- Post-procedure pain or discomfort: Usually mild and self-limited.

Careful patient selection, adherence to procedural protocols, and prompt recognition and management of complications are essential.

Post-Procedure Care and Follow-Up

After enteroscopy, patients are monitored for signs of complications such as abdominal pain, bleeding, or signs of perforation. Those who have received sedation are observed until fully awake and stable. Oral intake is resumed once the risk of aspiration has passed. Biopsy and pathology results are discussed with the patient, and further management is planned according to findings. In the Indian context, cultural sensitivity and clear communication about the results and next steps are important for patient satisfaction and adherence.

Comparison with Other Modalities

While enteroscopy is invaluable for direct visualisation and intervention, it is complemented by other diagnostic modalities, such as:

- Capsule endoscopy: Non-invasive, excellent for screening, but lacks therapeutic capability.

- Radiological imaging: CT enterography and MR enterography provide detailed anatomical information and are particularly useful for extraluminal disease or when enteroscopy is contraindicated.

- Barium studies: Less commonly used today, but may still play a role in select cases.

The choice of modality often depends on local expertise, availability, patient preference, and clinical context.

Nursing Care for Patients Undergoing Enteroscopy

The nursing care surrounding this procedure is multifaceted, encompassing pre-procedural preparation, intra-procedural support, and post-procedural management, all tailored to ensure patient safety, comfort, and optimal outcomes.

Pre-Procedure Nursing Care

Patient Assessment and Preparation

Comprehensive pre-procedure assessment is critical. Nurses should:

- Obtain a detailed medical history, including allergies, comorbidities (especially cardiopulmonary diseases), previous reactions to sedation or anaesthesia, and current medications (notably anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, and diabetic medications).

- Perform baseline vital sign measurements and physical examination, with particular attention to cardiovascular and respiratory status.

- Assess for contraindications such as suspected bowel perforation, severe coagulopathy, or unstable medical conditions.

- Evaluate the patient’s understanding of the procedure and address any anxieties or concerns, providing clear explanations about what to expect before, during, and after the enteroscopy.

Informed Consent

The nurse must ensure that the patient (or their legal representative) has provided informed consent for the procedure. This involves verifying that the patient understands the indications, risks, benefits, and potential alternatives. The nurse acts as a patient advocate, clarifying information and facilitating communication between the patient and the endoscopist as needed.

Bowel Preparation

A clean small bowel is essential for adequate visualisation. The specific preparation regimen varies depending on institutional protocols and the type of enteroscopy. Key nursing responsibilities include:

- Educating the patient about dietary restrictions (often clear fluids for 24 hours before the procedure) and the timing and administration of bowel cleansing agents.

- Monitoring the patient’s tolerance of the preparation, watching for signs of dehydration or electrolyte imbalance, and encouraging adequate fluid intake if permitted.

- Ensuring the patient adheres to fasting instructions, typically nil by mouth for at least 6-8 hours prior to the procedure.

Medication Management

Medications may need to be adjusted or withheld before enteroscopy. Nurses should:

- Consult with the medical team regarding the management of anticoagulants, antiplatelet drugs, insulin, and oral hypoglycaemics.

- Document all current medications and any changes made in preparation for the procedure.

- Monitor for potential withdrawal effects or complications from medication omissions.

Psychological Support

Undergoing an endoscopic procedure can be anxiety-provoking. Nurses should provide reassurance, answer questions, and offer emotional support. Empathy, active listening, and clear communication can alleviate fears and foster trust.

Intra-Procedure Nursing Care

Preparation of the Environment and Equipment

Ensuring a safe and efficient procedural environment is paramount. The nurse is responsible for:

- Preparing and checking all necessary equipment, including the enteroscope, light source, suction apparatus, monitoring devices, and resuscitation equipment.

- Ensuring the availability of ancillary supplies such as biopsy forceps, snares, injection needles, haemostatic agents, and specimen containers.

- Maintaining strict aseptic technique to prevent infection.

Patient Positioning and Comfort

The nurse assists in positioning the patient, typically in the left lateral decubitus position, unless otherwise specified. Padding and support should be provided to prevent pressure injuries and ensure comfort, especially for prolonged procedures.

Monitoring and Sedation

Continuous monitoring of the patient’s physiological status is essential throughout the procedure. The nurse should:

- Monitor vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation) at regular intervals and respond promptly to any deviations.

- Assess the level of consciousness and comfort, particularly if conscious sedation is used.

- Administer sedative and analgesic medications as prescribed, observing for adverse reactions such as respiratory depression, hypotension, or allergic responses.

- Maintain intravenous access and be prepared to manage complications, including airway compromise or anaphylaxis.

Assisting the Endoscopist

Nurses play a hands-on role during enteroscopy, including:

- Handing instruments and devices to the endoscopist promptly and efficiently.

- Applying abdominal pressure or changing patient position as directed to facilitate passage of the scope.

- Collecting and labelling specimens correctly for histopathological or microbiological analysis.

- Documenting procedural details, interventions performed, and any complications encountered.

Patient Advocacy and Communication

The nurse serves as the patient’s advocate, ensuring dignity, privacy, and safety are maintained at all times. Clear communication with the patient (if conscious) and the procedural team is vital for coordinated care and rapid response to any issues.

Post-Procedure Nursing Care

Immediate Recovery and Monitoring

After enteroscopy, patients require close observation to detect and manage complications. Nursing responsibilities include:

- Monitoring vital signs and level of consciousness until the effects of sedation or anaesthesia have worn off.

- Assessing for signs of complications, such as abdominal pain, distension, bleeding (e.g., melaena, haematemesis), perforation (e.g., peritonitis, tachycardia, hypotension), or allergic reactions.

- Ensuring a patent airway and monitoring oxygen saturation, particularly in patients at risk of respiratory depression.

- Documenting all observations and interventions in the patient’s medical record.

Pain Management and Comfort

Mild abdominal discomfort or bloating is common post-procedure. Nurses should:

- Assess pain using validated scales and provide analgesia as prescribed.

- Encourage mobilisation as tolerated to reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis and promote recovery.

- Offer reassurance and address any concerns regarding post-procedural symptoms.

Resumption of Diet and Medications

The timing of reintroducing oral intake depends on the procedure performed and the patient’s clinical status. Nurses should:

- Follow medical advice regarding resumption of diet and fluids, typically starting with clear liquids and advancing as tolerated.

- Restart regular medications, including anticoagulants, as per protocol and after consultation with the medical team.

- Monitor for adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, or difficulty swallowing.

Patient Education and Discharge Planning

Before discharge, nurses must ensure the patient (and carers, if applicable) understands:

- Signs and symptoms that require urgent medical attention, such as severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, fever, or rectal bleeding.

- Instructions regarding wound care (if applicable), activity restrictions, and follow-up appointments.

- How and when to resume normal activities, including work and driving.

- Contact information for the endoscopy unit or emergency services in case of complications.

Documentation

Accurate and comprehensive documentation is a cornerstone of safe practice. Nurses should record all aspects of care, including assessments, interventions, patient responses, education provided, and any complications or incidents.

Managing Complications

Early Recognition and Response

Although enteroscopy is generally safe, complications can occur. The most common include:

- Perforation: Presents with acute abdominal pain, tachycardia, hypotension, and signs of peritonitis. Immediate medical attention is required.

- Bleeding: May be immediate or delayed, manifesting as haematemesis, melaena, or haemodynamic instability. Monitoring and rapid intervention are essential.

- Infection: Rare but possible, particularly if therapeutic interventions are performed. Monitor for fever, chills, and localised signs of infection.

- Adverse reactions to sedation: Respiratory depression, hypotension, or allergic responses must be promptly recognised and managed.

Nurses should be prepared to initiate emergency protocols, provide supportive care, and communicate promptly with the medical team.

Special Considerations

Paediatric Patients

Caring for children undergoing enteroscopy requires additional considerations, including age-appropriate communication, involvement of parents or guardians, and modification of sedation and monitoring protocols.

Older Adults and High-Risk Patients

Older adults may have multiple comorbidities and increased vulnerability to complications. Comprehensive assessment, careful medication management, and close monitoring are essential in this group.

Patients with Disabilities or Communication Barriers

Adaptations may be required to ensure effective communication, informed consent, and provision of appropriate support throughout the peri-procedural period.

REFERENCES

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Balloon Assisted or “Deep” Enteroscopy https://www.asge.org/home/about-asge/newsroom/media-backgrounders-detail/balloon-assisted-enteroscopy.

- ASGE Technology Committee; Chauhan SS, Manfredi MA, Abu Dayyeh BK, Enestvedt BK, Fujii-Lau LL, Komanduri S, Konda V, Maple JT, Murad FM, Pannala R, Thosani NC, Banerjee S. Enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Dec;82(6):975-90. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.012. Epub 2015 Sep 19. Erratum in: Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Nov;86(5):929. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.09.026. PMID: 26388546.

- Cooley DM, Walker AJ, Gopal DV. From Capsule Endoscopy to Balloon-Assisted Deep Enteroscopy: Exploring Small-Bowel Endoscopic Imaging.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4836584/). Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015;11(3):143-154.

- Moeschler O, Mueller MK. Deep enteroscopy – indications, diagnostic yield and complications. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb 7;21(5):1385-93. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1385. PMID: 25663758; PMCID: PMC4316081.

- Teshima CW, May G. Small bowel enteroscopy https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3352842/). Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(5):269-275.

- Baek, N., Chang, D.K. (2022). Types of Enteroscopy. In: Chun, H.J., Seol, SY., Choi, MG., Cho, J.Y. (eds) Small Intestine Disease. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7239-2_22

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.