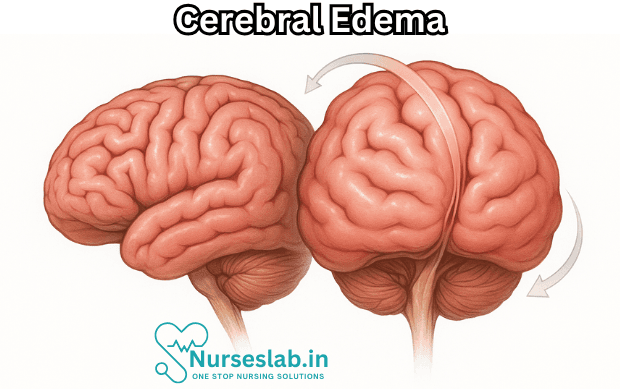

Cerebral edema, or swelling in the brain, can be life-threatening and needs immediate treatment. Causes include brain injuries, infections and inflammatory conditions. Symptoms can include visual disturbance, headaches and nausea. Providers may recommend medications or surgery.

Introduction

Cerebral edema, characterised by an abnormal accumulation of fluid within the brain parenchyma, is a critical medical condition that can lead to increased intracranial pressure (ICP), neurological deterioration, and potentially fatal outcomes. This phenomenon is encountered across a wide spectrum of neurological disorders, ranging from traumatic brain injury and stroke to infections and metabolic imbalances.

Globally, cerebral edema contributes to substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in settings of acute neurological insults. The epidemiology varies based on the underlying cause, with higher prevalence observed in cases of severe traumatic brain injury, large cerebral infarctions, and central nervous system infections. The significance of cerebral edema lies not only in its direct effects but also in its secondary impact on brain function due to compression and herniation.

Types of Cerebral Edema

Cerebral edema is broadly classified into four principal types, each defined by distinct pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical contexts:

1. Vasogenic Edema

Vasogenic edema arises from disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), leading to extravasation of plasma proteins and fluid into the interstitial space. This is commonly seen in brain tumours, abscesses, trauma, and inflammatory conditions. The predilection for white matter is a hallmark of vasogenic edema due to its greater extracellular space and permeability.

2. Cytotoxic Edema

Cytotoxic edema is the result of cellular injury and impaired ionic homeostasis, particularly involving neurons and glial cells. It is most prominent in conditions such as ischaemic stroke, hypoxic injury, and certain intoxications. Unlike vasogenic edema, cytotoxic edema predominantly affects grey matter and is associated with intracellular swelling due to failure of energy-dependent ion pumps.

3. Interstitial Edema

Interstitial edema occurs due to transependymal movement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the setting of obstructive hydrocephalus. Elevated ventricular pressure forces CSF across the ependymal lining into the surrounding brain tissue, resulting in periventricular lucency on imaging.

4. Osmotic Edema

Osmotic edema develops when there is a disturbance in serum osmolality, such as rapid correction of hypernatremia or hyponatremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, or severe hepatic failure. The resultant osmotic gradient drives water into brain cells, causing diffuse swelling.

Etiology and Risk Factors

The aetiology of cerebral edema is multifactorial, with numerous conditions predisposing individuals to its development. Major causes and risk factors include:

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Direct mechanical injury disrupts vascular integrity and cellular metabolism.

- Ischaemic and Haemorrhagic Stroke: Reduced perfusion and vascular rupture initiate both cytotoxic and vasogenic mechanisms.

- Brain Tumours: Neoplastic infiltration and associated inflammation compromise the BBB.

- Infections: Meningitis, encephalitis, and abscesses provoke inflammatory responses leading to BBB breakdown.

- Metabolic Derangements: Hyponatraemia, hyperosmolar states, and hepatic encephalopathy alter osmotic gradients.

- High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE): Hypobaric hypoxia at high elevations can trigger cerebral swelling.

- Acute Liver Failure: Ammonia toxicity and astrocyte dysfunction contribute to cerebral edema.

- CNS Procedures and Surgery: Post-operative swelling may result from manipulation, haemorrhage, or infection.

- Intoxications: Some toxins and drugs (e.g., water intoxication, barbiturates) can cause cytotoxic or osmotic edema.

Certain populations are at higher risk, including children, elderly patients, and those with pre-existing neurological or systemic illnesses.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological basis of cerebral edema involves complex interactions between vascular permeability, cellular metabolism, and fluid homeostasis. Core mechanisms include:

Disruption of Blood-Brain Barrier

In vasogenic edema, inflammatory mediators, tumour cells, or trauma cause endothelial tight junctions of the BBB to loosen, permitting plasma constituents to infiltrate the brain’s extracellular space. This process is often self-perpetuating, as extravasated proteins draw additional water by osmotic forces.

Cellular Energy Failure

Cytotoxic edema is rooted in energy depletion, typically secondary to hypoxia or ischaemia. The loss of ATP impairs sodium-potassium ATPase pumps, resulting in sodium and water influx into neurons and glia, causing cellular swelling. Excitotoxicity, driven by glutamate release, exacerbates neuronal injury.

Altered Osmotic Gradients

Osmotic edema reflects imbalances in systemic and cerebral osmolality. Rapid shifts in serum sodium or glucose levels can overwhelm the brain’s adaptive mechanisms, leading to water ingress and global swelling.

CSF Dynamics

In hydrocephalus, increased intraventricular pressure forces CSF into periventricular white matter, resulting in interstitial edema. This impairs neuronal signalling and may contribute to raised ICP.

Raised Intracranial Pressure

Regardless of the initiating event, cerebral edema increases intracranial volume, reducing cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) and risking herniation syndromes. The Monro-Kellie doctrine underscores the fixed cranial capacity, wherein expansion of one component (brain, blood, CSF) necessitates compensatory reduction in others.

Clinical Features

The clinical manifestations of cerebral edema are diverse, depending on the severity, rate of development, and underlying cause. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Headache: Often diffuse and severe, worsening with increased ICP.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Resulting from stimulation of the medullary vomiting centre.

- Altered Consciousness: Ranging from confusion and drowsiness to stupor and coma.

- Focal Neurological Deficits: Weakness, aphasia, or visual disturbances if localised swelling compresses functional areas.

- Papilloedema: Swelling of the optic disc observed on fundus examination, indicative of raised ICP.

- Seizures: Due to cortical irritation and disruption of electrical activity.

- Cushing’s Triad: Hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respiration—signs of impending brain herniation.

- Decerebrate or Decorticate Posturing: Reflects severe brainstem compression.

Progression of cerebral edema may be insidious or rapid, with acute deterioration signalling life-threatening complications such as uncal, central, or tonsillar herniation.

Diagnostic Approaches

Early and accurate diagnosis of cerebral edema is crucial for guiding management. Diagnostic modalities include:

Clinical Assessment

A thorough history and neurological examination remain foundational. Key aspects include onset and progression of symptoms, risk factors, and assessment of Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

Neuroimaging

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Rapid and widely available, CT can detect brain swelling, effacement of sulci, midline shift, and herniation. Vasogenic edema appears as hypodense regions in white matter, while cytotoxic changes are more diffuse.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Superior sensitivity for early and subtle changes, MRI sequences (T2, FLAIR, DWI) help differentiate edema types and assess underlying pathology.

- Advanced Imaging: Perfusion studies, MR spectroscopy, and functional MRI may provide additional insights into cerebral blood flow and metabolism.

Laboratory Investigations

- Serum Electrolytes: Assess for hyponatraemia, hyperglycaemia, or other metabolic derangements.

- Inflammatory Markers: Elevated CRP, ESR, or leucocytosis may indicate infection or inflammation.

- CSF Analysis: Useful in suspected meningitis, encephalitis, or subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

In selected cases, especially in critical care, direct measurement of ICP via intraventricular catheters or parenchymal probes guides therapeutic interventions.

Management and Treatment

Management of cerebral edema is multifaceted, aiming to reduce brain swelling, control ICP, and address the underlying cause. Treatment approaches include:

Medical Management

- Osmotherapy: Administration of hyperosmolar agents such as mannitol or hypertonic saline draws water out of brain tissue, reducing ICP. Careful monitoring of serum osmolality is essential to prevent rebound edema.

- Corticosteroids: Useful in vasogenic edema associated with brain tumours or abscesses, steroids stabilise the BBB and reduce inflammatory responses. Their use in other contexts (e.g., traumatic brain injury) is controversial.

- Diuretics: Agents like furosemide may be adjuncts to osmotherapy in selected cases.

- Control of Metabolic Factors: Correction of electrolyte imbalances, glucose control, and avoidance of rapid osmotic shifts are critical.

- Anticonvulsants: Prophylactic or therapeutic use in patients with seizures.

- Antibiotics/Antivirals: Directed therapy in cases of infection-induced edema.

Supportive Care

- Airway Protection: Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary in comatose patients.

- Fluid Management: Maintenance of euvolemia and careful monitoring of input/output.

- Positioning: Elevation of the head to 30 degrees can facilitate venous drainage and lower ICP.

- Temperature Control: Prevention of hyperthermia, which can exacerbate cerebral metabolic demands.

Surgical Management

- Decompressive Craniectomy: Removal of a portion of the skull allows expansion of swollen brain tissue, reducing ICP in refractory cases.

- CSF Drainage: External ventricular drains may relieve hydrocephalus-associated interstitial edema.

- Evacuation of Mass Lesions: Removal of haematomas, tumours, or abscesses when indicated.

Emerging Therapies

- Hypothermia: Induced cooling is under investigation for neuroprotection and reduction of metabolic demands.

- Targeted Molecular Agents: Agents targeting aquaporin channels, inflammatory mediators, or BBB stabilisation are in experimental phases.

Complications

If not promptly managed, cerebral edema can lead to devastating complications, including:

- Brain Herniation: Life-threatening displacement of brain structures through rigid cranial compartments (uncal, central, tonsillar).

- Permanent Neurological Deficits: Irreversible damage to functional brain areas due to prolonged compression or ischaemia.

- Seizure Disorders: Persistent cortical irritation may result in chronic epilepsy.

- Hydrocephalus: Obstructive or communicative hydrocephalus may develop secondary to altered CSF dynamics.

- Infections: Secondary infections, including pneumonia and urinary tract infections, may occur in immobilised or ventilated patients.

- Death: Severe or untreated cerebral edema is often fatal due to herniation or profound neurological dysfunction.

Prognosis

The outcome of cerebral edema depends on multiple factors, including the underlying cause, severity and rapidity of onset, timeliness of intervention, and patient comorbidities. Key prognostic indicators include:

- Initial Glasgow Coma Scale score

- Extent of brain swelling and midline shift on imaging

- Response to medical and surgical therapies

- Presence of complications such as herniation or persistent seizures

While some patients recover fully with appropriate treatment, others may experience long-term cognitive, motor, or sensory deficits. Early rehabilitation and multidisciplinary care are crucial for optimising functional outcomes.

Nursing Care of Patients with Cerebral Edema (Brain Swelling)

Nurses play a crucial role in the early identification, continuous monitoring, and comprehensive care of patients experiencing cerebral edema.

Assessment and Early Recognition

Early recognition is vital to prevent irreversible damage. Nursing assessment should focus on:

- Neurological Status: Frequent monitoring using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) to assess consciousness, orientation, and response to stimuli.

- Pupillary Response: Checking for changes in pupil size, symmetry, and reactivity to light.

- Vital Signs: Monitoring for Cushing’s triad (bradycardia, irregular respirations, hypertension), which indicates increased ICP.

- Motor Function: Evaluating for weakness, posturing, or abnormal movements.

- Speech and Behavior: Any sudden changes in speech, confusion, restlessness, or agitation.

Documentation of findings and prompt reporting of any deterioration are essential components of nursing care.

Nursing Diagnoses

Common nursing diagnoses for patients with cerebral edema include:

- Ineffective cerebral tissue perfusion related to increased ICP

- Risk for impaired airway clearance

- Risk for aspiration

- Impaired physical mobility

- Self-care deficit

- Risk for infection (especially with invasive monitoring devices or mechanical ventilation)

- Disturbed sensory perception

- Acute confusion

- Anxiety (patient and family)

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions are focused on maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion, minimizing secondary injury, promoting safety, and supporting physiological needs.

1. Airway Management and Oxygenation

- Maintain a patent airway; position the patient in a way that facilitates breathing (usually head-of-bed elevated 30 degrees, unless contraindicated).

- Monitor respiratory rate and pattern; assess for signs of respiratory distress or hypoventilation.

- Administer supplemental oxygen as ordered to maintain optimal oxygen saturation.

- Be prepared for intubation and mechanical ventilation if airway protection is compromised.

2. Intracranial Pressure Monitoring and Control

- Monitor neurological status frequently (at least every 1-2 hours or as per protocol).

- Assess for signs of increased ICP: change in level of consciousness, headache, vomiting, altered pupil responses, posturing.

- Maintain head alignment (avoid flexion or rotation) to facilitate venous drainage from the brain.

- Avoid activities that increase ICP, such as excessive suctioning, coughing, or rapid position changes.

- Administer osmotic diuretics (e.g., mannitol), corticosteroids (for tumors), or hypertonic saline as prescribed.

- Monitor fluid and electrolyte balance carefully, particularly serum sodium and osmolality.

- Monitor for complications of invasive ICP monitoring if present, such as infection or hemorrhage.

3. Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

- Strictly monitor intake and output; use a urinary catheter if necessary.

- Assess for signs of fluid overload or dehydration.

- Avoid hypotonic fluids, as they can worsen cerebral swelling.

- Monitor laboratory values closely (sodium, potassium, osmolality).

4. Positioning and Mobility

- Keep the head of bed elevated at 30 degrees unless contraindicated, to promote venous return and reduce ICP.

- Avoid Trendelenburg position and extreme hip flexion.

- Reposition patient at regular intervals to prevent pressure ulcers, while minimizing abrupt movements that could increase ICP.

- Assess skin integrity frequently.

5. Seizure Precautions

- Implement seizure precautions (side rails up, padded rails, suction and oxygen available at bedside).

- Administer antiepileptic medications as prescribed.

- Monitor for subtle signs of seizure activity, as they may be masked by altered consciousness.

6. Nutrition and Gastrointestinal Care

- Establish enteral or parenteral feeding as soon as possible if the patient is unable to eat.

- Monitor for signs of aspiration; keep suction equipment at the bedside.

- Assess for bowel sounds and monitor for constipation or paralytic ileus.

- Maintain glycemic control to avoid hyper- or hypoglycemia, both of which can worsen neurological outcomes.

7. Infection Prevention

- Follow strict hand hygiene and aseptic techniques, especially if invasive devices are in use.

- Monitor for signs of infection (fever, elevated white count, purulent drainage).

- Turn patient regularly and provide skin care to prevent pressure sores.

- Provide oral care to reduce risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

8. Psychological and Emotional Support

- Provide reassurance and clear information to patient (if possible) and family regarding condition and care plan.

- Encourage family involvement in care as appropriate.

- Assess for signs of anxiety, depression, or emotional distress; provide referrals to support services if needed.

9. Education and Discharge Planning

- Educate family about the nature of cerebral edema, expected course, warning signs of deterioration, and the importance of follow-up care.

- Prepare for long-term rehabilitation needs, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

- Provide guidance on medication management and lifestyle modifications to prevent recurrence (e.g., managing risk factors for stroke or traumatic injury).

Collaborative Care

Nurses should work closely with a multidisciplinary team, including physicians, neurologists, respiratory therapists, rehabilitation specialists, and social workers to ensure comprehensive management. Early involvement of physical and occupational therapy helps prevent complications related to immobility and supports optimal recovery.

Monitoring for Complications

It is essential to monitor for complications such as:

- Brain herniation

- Seizures

- Nosocomial infections (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infections)

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- Pressure ulcers

- Electrolyte imbalances

Early recognition and prompt intervention for these complications can be life-saving.

Documentation

Meticulous documentation of neurological assessments, interventions performed, patient response, and any changes in condition is crucial. Timely communication with the healthcare team regarding deterioration in patient status must be ensured.

REFERENCES

- Cook A, Morgan Jones G, Hawryluk G, et al. Guidelines for the Acute Treatment of Cerebral Edema in Neurocritical Care Patients. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-00959-7. Neurocrit Care. 2020;32;647–666.

- Turner REF, Gatterer H, Falla M, Lawley JS. High-altitude cerebral edema: its own entity or end-stage acute mountain sickness? J Appl Physiol. 2021;131(1):313-325. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00861.2019

- Jha R, Raikwar S, Mihaljevic S, et al. Emerging therapeutic targets for cerebral edema.. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34844502/ Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2021 Nov;25(11):917-938.

- Munakomi S, M Das J. Ventriculostomy/ . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545317/. [Updated 2023 Apr 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- Nehring S, Tadi P, Tenny S. Cerebral Edema. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537272/. [Updated 2022 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- Stokum JA, et al. (2020). Emerging pharmacological treatments for cerebral edema: Evidence from clinical studies.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7122796/

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.