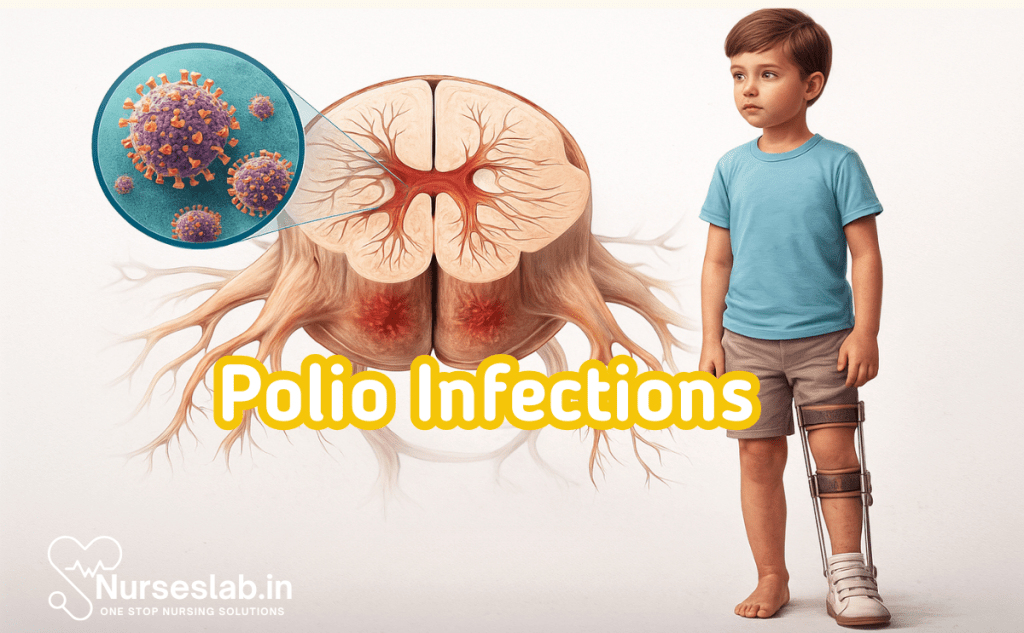

Polio infections are caused by poliovirus, an enterovirus that spreads via the fecal-oral route. While many cases are asymptomatic, severe infections can lead to paralysis. Vaccination, surveillance, and public health initiatives are essential in nursing and global disease control.

Introduction

Poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio, is a highly infectious viral disease that has shaped global public health initiatives for nearly a century. Caused by the poliovirus, polio predominantly affects children under the age of five, but it can also impact adults. While most infections are asymptomatic or mild, a small proportion can lead to irreversible paralysis and, in severe cases, death. The global fight against polio has witnessed significant triumphs, particularly with the advent of effective vaccines and coordinated eradication efforts.

Antigenic Types of Poliovirus

Poliovirus Serotypes

Poliovirus belongs to the genus Enterovirus within the family Picornaviridae. There are three antigenically distinct serotypes of poliovirus, each with unique epidemiological and clinical significance:

- Type 1: Responsible for most cases of paralytic polio and the majority of outbreaks worldwide.

- Type 2: Historically caused epidemics but has been declared eradicated globally since 2015.

- Type 3: Less common but still capable of causing paralytic disease; declared eradicated in 2019.

Molecular Characteristics

Polioviruses are small, non-enveloped, icosahedral viruses with a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 7,500 nucleotides. The viral capsid comprises four proteins (VP1–VP4), with VP1, VP2, and VP3 forming the surface and containing the antigenic sites. The antigenic differences between the three serotypes are determined by variations in these capsid proteins, particularly VP1. These differences are crucial as immunity to one serotype does not confer protection against the others, necessitating trivalent vaccine formulations.

Relevance of Antigenic Types

Understanding the antigenic diversity of poliovirus is critical for vaccine design, surveillance, and outbreak control. The persistence of wild poliovirus type 1 in certain regions underscores the need for robust immunisation strategies, while the eradication of types 2 and 3 demonstrates the impact of targeted vaccination campaigns.

Pathogenesis of Poliovirus Infection

Mechanism of Infection

Poliovirus is transmitted primarily via the faecal-oral route, although oral-oral transmission can also occur. The virus enters the body through ingestion of contaminated water or food. Upon entry, it multiplies initially in the oropharyngeal and intestinal mucosa, particularly in the tonsils and Peyer’s patches of the small intestine.

Viral Replication and Spread

After local replication, poliovirus invades regional lymphoid tissue and enters the bloodstream, resulting in a primary viraemia. In most cases, the infection is contained at this stage by the host immune response. However, in approximately 1% of infected individuals, the virus overcomes immune defences and disseminates via secondary viraemia. During this phase, poliovirus can cross the blood-brain barrier or enter the central nervous system (CNS) by retrograde axonal transport along motor neurons.

Host Response

The host mounts both humoral and cellular immune responses against poliovirus. Secretory IgA in the gut limits intestinal replication and transmission, while serum neutralising antibodies (mainly IgG) are essential for protection against paralytic disease. Cellular immunity plays a supportive role in viral clearance. Genetic and environmental factors, such as malnutrition and concurrent infections, can modulate susceptibility and outcome.

Clinical Manifestations of Polio

Stages of Disease

Polio infection exhibits a broad clinical spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic infection to severe paralytic disease. The clinical course can be divided into several forms:

- Asymptomatic Infection: Constitutes about 90–95% of all cases. The virus is confined to the gut, and individuals serve as silent reservoirs for community transmission.

- Abortive Poliomyelitis (Minor Illness): Occurs in about 4–8% of cases. Presents as a non-specific, self-limiting febrile illness with symptoms such as fever, malaise, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, and headache. There is no CNS involvement.

- Non-paralytic Poliomyelitis (Aseptic Meningitis): Seen in 1–2% of infections. Characterised by symptoms of abortive illness plus signs of meningeal irritation, such as neck stiffness, photophobia, and muscle tenderness. Recovery is usually complete.

- Paralytic Poliomyelitis: The most severe form, affecting less than 1% of infections. It can be further classified into:

- Spinal Polio: Involvement of anterior horn cells of the spinal cord, resulting in asymmetric, flaccid paralysis, most commonly affecting the lower limbs.

- Bulbar Polio: Involvement of cranial nerve nuclei, leading to respiratory and swallowing difficulties.

- Bulbospinal Polio: Combination of spinal and bulbar features.

Complications

Major complications include acute respiratory failure (due to paralysis of respiratory muscles), secondary infections, musculoskeletal deformities, and, rarely, death. Long-term sequelae, such as post-polio syndrome, may develop years after the initial illness, characterised by progressive muscle weakness, fatigue, and pain.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Poliovirus Infection

Specimen Collection

Early and appropriate specimen collection is vital for accurate diagnosis. The preferred specimens are:

- Stool samples: At least two samples, collected 24–48 hours apart within 14 days of symptom onset.

- Throat swabs: Useful in the early phase of infection.

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): For cases with suspected CNS involvement.

Diagnostic Methods

- Virus Isolation: Gold standard for diagnosis. Specimens are inoculated onto susceptible cell lines (e.g., L20B, RD cells). Cytopathic effects are observed, and poliovirus is identified by neutralisation assays with type-specific antisera.

- Serology: Detection of poliovirus-specific IgM or a fourfold rise in neutralising antibody titres between acute and convalescent sera. Serology is less commonly used due to cross-reactivity and the rapid development of antibodies after infection or vaccination.

- Molecular Techniques (PCR): Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) enables rapid detection and serotyping of poliovirus RNA in clinical specimens. It is highly sensitive and specific, and plays a critical role in surveillance and outbreak investigations.

Interpretation of Results

Isolation of poliovirus from stool or throat specimens confirms infection. Detection of wild-type versus vaccine-derived poliovirus is essential for public health decision-making and is performed by sequencing viral isolates. Negative results do not exclude infection if samples are collected late or improperly handled.

Polio Vaccines

Types of Polio Vaccines

Two primary types of vaccines are used in the prevention of poliomyelitis:

- Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV): Developed by Jonas Salk in 1955, IPV contains inactivated (killed) polioviruses of all three serotypes. It is administered by injection and induces systemic immunity.

- Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV): Developed by Albert Sabin in 1961, OPV contains live, attenuated polioviruses of all three serotypes. It is administered orally, replicates in the gut, and induces both systemic and mucosal immunity.

Mechanism of Action and Immunogenicity

IPV stimulates the production of serum neutralising antibodies, providing robust protection against paralytic disease. However, it induces limited mucosal immunity, thereby offering less protection against intestinal infection and virus shedding. OPV, on the other hand, induces both systemic and local (intestinal) immunity, effectively interrupting transmission by reducing viral replication and excretion in the gut. OPV’s ease of administration, low cost, and ability to confer herd immunity have made it the cornerstone of global eradication campaigns. However, rare cases of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) and circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) are potential drawbacks of OPV.

Injectable vs Oral Polio Vaccine

| Parameter | Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV) | Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) |

| Composition | Killed (inactivated) poliovirus of all three serotypes | Live, attenuated poliovirus of all three serotypes |

| Route of Administration | Intramuscular or subcutaneous injection | Oral drops |

| Induced Immunity | Systemic (humoral) immunity | Systemic and mucosal (intestinal) immunity |

| Prevention of Transmission | Limited effect on intestinal replication; does not interrupt transmission efficiently | Interrupts transmission by preventing gut replication and shedding |

| Herd Immunity | Limited | Strong (due to secondary spread of vaccine virus) |

| Efficacy | High against paralytic disease | High against both infection and paralytic disease |

| Side Effects | Minor local reactions (pain, swelling); no risk of VAPP | Rare risk of VAPP and cVDPVs |

| Suitability in Immunocompromised Individuals | Safe | Contraindicated |

| Cost | Relatively higher | Lower |

| Storage Requirements | Less stringent (refrigeration) | Strict cold chain required |

Epidemiology of Polio

Global and Regional Trends

Prior to the introduction of vaccines, poliomyelitis was endemic worldwide and a leading cause of childhood disability. The launch of mass immunisation programmes, notably the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) in 1988, has resulted in a dramatic reduction in polio incidence—over 99% globally. As of 2025, wild poliovirus remains endemic in only two countries: Afghanistan and Pakistan. India, once a global epicentre, was certified polio-free in 2014 following sustained vaccination drives and robust surveillance.

Eradication Efforts

Eradication strategies have centred on high routine immunisation coverage, supplementary immunisation activities (SIAs), and environmental surveillance. The use of OPV in mass campaigns has been pivotal in interrupting wild poliovirus transmission. Switches from trivalent to bivalent OPV and the phased introduction of IPV have minimised risks associated with vaccine-derived polioviruses. The certification of regions as polio-free follows at least three years of zero wild poliovirus cases and high-quality surveillance.

Outbreaks and Surveillance

Despite remarkable progress, sporadic outbreaks of wild poliovirus and cVDPVs continue to challenge eradication efforts. Surveillance systems, including acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) monitoring and environmental sampling of sewage, are critical for early detection and rapid response. Molecular epidemiology, using genome sequencing, facilitates tracking of virus origins and transmission pathways.

Challenges in Eradication

Persistent barriers include armed conflict, population displacement, vaccine hesitancy, logistical hurdles in remote areas, and lapses in immunisation coverage. The emergence of cVDPVs—viruses that have genetically mutated from the vaccine strain and regained neurovirulence—necessitates vigilant monitoring and tailored immunisation responses. The COVID-19 pandemic has further disrupted routine vaccination services in some regions, risking resurgence of polio.

Conclusion

Polio remains a formidable public health challenge, despite the near-eradication of the disease through concerted global efforts. Understanding the antigenic types, pathogenesis, clinical spectrum, diagnostic modalities, and vaccine strategies is essential for all healthcare providers. While the injectable and oral polio vaccines have complementary roles, the ultimate goal remains the complete elimination of both wild and vaccine-derived polioviruses. Continued vigilance, innovation in vaccine delivery, and sustained political and community commitment are key to consigning polio to history.

Future Directions

- Development and deployment of novel oral polio vaccines (nOPVs) with reduced risk of reversion and cVDPVs.

- Strengthening surveillance and outbreak response, especially in high-risk areas.

- Integration of polio eradication activities with broader health systems strengthening and immunisation services.

- Addressing vaccine hesitancy through culturally sensitive health communication and community engagement.

- Sustained funding and international cooperation to maintain progress and prevent resurgence.

In summary, the global polio eradication initiative stands as a testament to the power of vaccines and international collaboration. The lessons learned from polio are invaluable for tackling other infectious diseases and future pandemics.

REFERENCES

- Apurba S Sastry, Essential Applied Microbiology for Nurses including Infection Control and Safety, First Edition 2022, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-9354659386

- Joanne Willey, Prescott’s Microbiology, 11th Edition, 2019, Innox Publishers, ASIN- B0FM8CVYL4.

- Anju Dhir, Textbook of Applied Microbiology including Infection Control and Safety, 2nd Edition, December 2022, CBS Publishers and Distributors, ISBN: 978-9390619450

- Gerard J. Tortora, Microbiology: An Introduction 13th Edition, 2019, Published by Pearson, ISBN: 978-0134688640

- Durrant RJ, Doig AK, Buxton RL, Fenn JP. Microbiology Education in Nursing Practice. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2017 Sep 1;18(2):18.2.43. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5577971/

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.