The Kasai procedure, while essential for infants with biliary atresia, is not curative, often necessitating long-term medical supervision and potential liver transplants. Nurses are crucial in ensuring the child’s welfare, development, and providing support to families throughout the process. In nursing management, a key focus is equipping families with the knowledge and confidence to care for their children effectively at home.

Understanding Biliary Atresia

Biliary atresia is a progressive, idiopathic disease characterized by the obliteration or discontinuity of the extrahepatic biliary system, resulting in obstruction of bile flow from the liver to the gallbladder and small intestine. The condition typically manifests within the first two months of life and, if left untreated, leads to cirrhosis, liver failure, and eventual death, often within the first two years.

The precise cause of biliary atresia remains unclear, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors, including viral infections or abnormal immune responses during fetal development. The hallmark symptoms include persistent jaundice, pale (acholic) stools, dark urine, and hepatomegaly. Laboratory tests reveal cholestasis, with elevated conjugated bilirubin and liver enzymes.

The Origins of the Kasai Procedure

The Kasai Procedure is named after the Japanese surgeon Dr. Morio Kasai, who first performed and described the operation in 1959. Prior to his innovation, biliary atresia was considered uniformly fatal. Dr. Kasai’s technique revolutionized pediatric surgery, offering hope to thousands of infants who, without intervention, had no chance of long-term survival. The procedure has since become the standard initial treatment for biliary atresia worldwide.

Indications for the Kasai Procedure

The Kasai Procedure is indicated for infants diagnosed with biliary atresia, typically between the ages of one month and three months. Early diagnosis and timely referral are paramount—outcomes correlate closely with the age at surgery. The ideal window for intervention is before 60 days of life, although children up to 90 days may still benefit.

Diagnosis is established via a combination of clinical presentation, laboratory studies, abdominal ultrasound, hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HIDA scan), and intraoperative cholangiography, which definitively demonstrates the absence of a patent extrahepatic biliary tree.

Surgical Technique

The Kasai Procedure is a technically demanding operation, requiring meticulous dissection and reconstruction. The core steps of the surgery include:

- Laparotomy: The abdomen is opened, and the liver and biliary tract are inspected. The gallbladder is often absent or atretic.

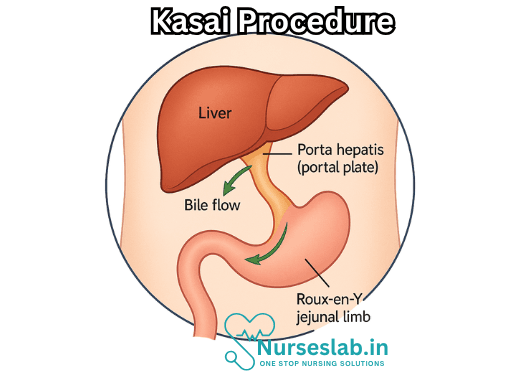

- Dissection of the Porta Hepatis: The fibrous remnants of the atretic extrahepatic bile ducts are dissected from the portal plate at the liver hilum. Extreme care is taken to avoid damaging the portal vein and hepatic artery branches.

- Creation of the Roux-en-Y Loop: A segment of the small intestine (usually jejunum) is isolated and anastomosed in a “Roux-en-Y” configuration to serve as a conduit for bile drainage.

- Anastomosis: The blind end of the Roux limb is sutured directly to the denuded surface of the porta hepatis—this is the “portoenterostomy.” The aim is to establish direct drainage of bile from microscopic intrahepatic ducts into the intestine.

- Completion: The continuity of the intestine is restored, and the abdomen is closed after ensuring hemostasis.

The surgery typically lasts several hours and is performed under general anesthesia, with careful monitoring of fluid status, coagulation, and cardiovascular stability.

Postoperative Management

The immediate postoperative period involves intensive monitoring for complications such as bleeding, infection, bile leakage, and anastomotic breakdown. Antibiotic prophylaxis is often administered to prevent ascending cholangitis, a common and serious complication.

Nutritional support is critical, as children with biliary atresia frequently suffer from malabsorption and failure to thrive. Supplementation with fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), medium-chain triglycerides, and caloric density are key aspects of care.

Over the long term, patients are monitored for resolution of jaundice, normalization of stool color, improvement in liver function tests, and growth. Chronic complications may include portal hypertension, recurrent cholangitis, and progressive liver fibrosis.

Expected Outcomes and Prognosis

The success of the Kasai Procedure is measured by the restoration of bile flow, resolution of jaundice, and delay or prevention of liver failure. Outcomes are highly dependent on the timing of surgery and the extent of liver damage at the time of intervention.

- Approximately 60-80% of children experience some restoration of bile flow and temporary resolution of jaundice if operated on before two months of age.

- Survival with the native liver at 10 years is reported between 30% and 50% in specialized centers.

- However, many children ultimately develop progressive liver disease and require liver transplantation during childhood or adolescence.

Despite its limitations, the Kasai Procedure often serves as an essential bridge to transplantation, allowing for growth, improved nutrition, and reduced perioperative risks.

Complications and Challenges

While the Kasai Procedure has dramatically improved survival for infants with biliary atresia, it is not curative. The major complications and challenges include:

- Cholangitis: Infection of the intrahepatic bile ducts is the most common postoperative complication, occurring in up to 60% of patients. Recurrent episodes can hasten liver damage.

- Progressive Liver Fibrosis: Even in the presence of bile flow, ongoing inflammation and fibrosis often lead to cirrhosis over time.

- Portal Hypertension: This can manifest as splenomegaly, variceal bleeding, and hypersplenism, requiring specialized management.

- Liver Failure: Signs include coagulopathy, encephalopathy, ascites, and declining synthetic liver function.

Advances and Innovations

Several modifications to the original Kasai Procedure have been explored, including laparoscopic approaches and tissue engineering, but the fundamental principles remain unchanged. Research continues into earlier diagnosis, the role of adjuvant therapies (such as steroids, antibiotics, and immunomodulation), and improved postoperative care.

Early screening—such as universal stool color cards to identify acholic stools—has been implemented in several countries to facilitate timely referral and intervention.

The Role of Liver Transplantation

For children who fail to achieve adequate bile drainage or develop end-stage liver disease, liver transplantation is the definitive treatment. The Kasai Procedure does not preclude subsequent transplantation; in fact, it often improves outcomes by allowing the child to reach a more optimal age and nutritional status for surgery.

The decision to proceed with transplantation is based on clinical deterioration, intractable complications, and poor growth. Survival rates after pediatric liver transplantation have improved dramatically, with many recipients enjoying good quality of life into adulthood.

Family Support and Multidisciplinary Care

Caring for a child with biliary atresia and post-Kasai management requires a multidisciplinary team, including pediatric surgeons, hepatologists, dietitians, infectious disease specialists, social workers, and support groups. Family education, psychosocial support, and access to specialized care are essential for optimizing outcomes.

Nursing Care of Patients Undergoing the Kasai Procedure

The Kasai Procedure, formally known as hepatoportoenterostomy, is a critical surgical intervention for infants diagnosed with biliary atresia—a rare but life-threatening condition in which the bile ducts outside and inside the liver are scarred and blocked. The purpose of the Kasai procedure is to restore bile flow from the liver into the intestine, thereby preventing progressive liver damage, cirrhosis, and eventual liver failure. As such, the role of nursing care both in the immediate postoperative phase and in ongoing management is vital to the child’s recovery, well-being, and long-term prognosis.

Preoperative Nursing Care

Nursing care begins even before the child enters the operating room. The nurse’s role at this stage is to prepare both patient and family for surgery, educate and offer psychological support, and optimize the infant’s physical condition for the best possible surgical outcome.

- Assessment and Baseline Data Collection: Thoroughly document the infant’s medical history, presenting symptoms, nutritional status, and laboratory values—including liver function tests, coagulation profile, and bilirubin levels.

- Education: Provide parents with clear information regarding biliary atresia, the rationale for the Kasai Procedure, its risks, expected outcomes, and the potential need for liver transplantation in the future.

- Nutritional Support: Collaborate with dietitians to ensure optimal nutrition—often complicated by fat malabsorption and vitamin deficiencies. Supplementation with fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and medium-chain triglycerides might be needed.

- Psychological Support: Encourage parents to express their concerns and fears; provide reassurance and connect them with support groups or counseling if desired.

Immediate Postoperative Nursing Care

The postoperative phase is characterized by close monitoring, prompt recognition of complications, and support of healing. The nurse serves as a vigilant advocate for the infant’s safety and comfort.

- Monitoring Vital Signs and Surgical Site: Regularly assess temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. Inspect the incision for bleeding, infection, dehiscence, or excessive drainage.

- Pain Management: Administer prescribed analgesics and assess pain levels using age-appropriate scales. Non-pharmacologic comfort measures (holding, gentle touch, swaddling) should also be employed.

- Fluid and Electrolyte Balance: Maintain strict input and output records. Monitor for signs of dehydration, especially since bile drainage is often increased post-surgery, which can lead to fluid loss.

- Nutritional Management: Gradually reintroduce oral feeding as tolerated. Monitor for vomiting, abdominal distention, or signs of feeding intolerance. Continue supplementation of vitamins and consider special formulas if the infant continues to demonstrate malabsorption.

- Infection Prevention: Practice meticulous hand hygiene, limit invasive procedures, and observe for signs of infection such as fever, elevated white blood cell count, redness or discharge at the incision site, and general malaise. Prophylactic antibiotics may be administered as per protocol.

- Liver Function Monitoring: Monitor laboratory values (bilirubin, AST, ALT, GGT, albumin, prothrombin time) regularly to assess ongoing liver function and detect early signs of deterioration.

- Bile Drainage Observation: Assess for quantity and quality of bile drainage from surgical drains or stoma. Sudden changes (decrease, increase, change in color) may signal complications such as obstruction or anastomotic leak.

- Prevention of Complications: Be alert for signs of cholangitis (fever, irritability, jaundice, pale stools), which is a potentially life-threatening infection of the bile ducts requiring urgent intervention.

- Family Education: Teach caregivers to recognize the signs and symptoms of complications, care for the surgical site, and maintain proper nutrition and medication regimens at home.

Long-term Nursing Care and Follow-up

The Kasai procedure is not a cure, and many children will require ongoing medical management and, sometimes, liver transplantation. Nurses play a pivotal role in supporting the child’s growth, development, and quality of life, as well as offering guidance to families.

- Monitoring Growth and Development: Regular assessment of weight, height, and developmental milestones. Early intervention services should be involved if delays are suspected.

- Continued Nutritional Support: Many children experience ongoing fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies. Regular bloodwork and dietary adjustments are essential. In some cases, tube feeding or parenteral nutrition may be necessary.

- Prevention and Early Detection of Cholangitis: Nurses should educate families to watch for signs of infection and provide clear instructions regarding when to seek medical attention. Prophylactic antibiotics or ursodeoxycholic acid may be prescribed to reduce risk.

- Liver Function Surveillance: Ongoing laboratory evaluation and imaging studies help detect worsening liver disease, portal hypertension, or other complications. Nurses coordinate appointments and ensure adherence to follow-up schedules.

- Immunizations: Children with chronic liver disease are at risk for severe infections. Ensure up-to-date vaccinations, including hepatitis A and B, pneumococcal, and annual influenza.

- Psychosocial Support: Chronic illness can be stressful for families. Nurses can facilitate access to counseling, peer support, and resources to help families cope emotionally and financially.

- Liver Transplant Preparation: Should liver function deteriorate, nurses prepare families for the possibility of transplantation by providing education, emotional support, and coordination with transplant teams.

Family-Centered Care and Education

Central to nursing management is empowering families to care for their children confidently and safely at home. Nurses are educators, advocates, and partners in care.

- Home Care Instructions: Provide written and verbal guidance on wound care, medication administration, recognizing early signs of infection, and when to contact the healthcare provider.

- Medication Management: Ensure families understand dosing schedules, side effects, and the importance of adherence to prescribed therapies.

- Community Resources: Connect families to home nursing services, social work, and support organizations for children with liver disease.

- Transition to Adult Care: As children grow, nurses should facilitate the transition from pediatric to adult liver care services, ensuring continuity and comprehensive management.

REFERENCES

- American Liver Foundation. Biliary Atresia. https://liverfoundation.org/liver-diseases/pediatric-liver-information-center/pediatric-liver-disease/biliary-atresia/). Last updated 7/29/2024.

- Vogt P, Tolly R, Clifton M, Austin T, Karlik J. The Development of an Enhanced Recovery Protocol for Kasai Portoenterostomy. Children (Basel). 2022 Oct 31;9(11):1675. doi: 10.3390/children9111675. PMID: 36360403; PMCID: PMC9688584.

- De Carvalho NMN, Torres SM, Cavalcante JCB, Ximenes ACM, Junior JAL, da Silveira Moreira SO. Hepatoportoenterostomy surgery technique. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30442462/). J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(8):1715-1718.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (U.S.). Biliary Atresia (https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/biliary-atresia). Last reviewed 9/2017.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (U.S.). Treatment for Biliary Atresia. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/biliary-atresia/treatment. Last reviewed 9/2017.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”