Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy is a surgical procedure used to treat chronic anal fissures by partially dividing the internal anal sphincter muscle, relieving hypertonic spasm, improving blood flow, and promoting wound healing—offering high success rates with minimal complications

Introduction

Lateral internal sphincterotomy is a surgical procedure primarily performed to treat chronic anal fissures—painful tears in the lining of the anus that often result in significant discomfort and impaired quality of life. As a well-established and effective intervention, lateral internal sphincterotomy has stood the test of time as the gold standard for cases where conservative medical management fails.

Background and Indications

Anal fissures are a common cause of anorectal pain and bleeding. Acute fissures frequently resolve with conservative management such as dietary modifications, topical agents, and sitz baths. However, chronic fissures, which persist for more than six weeks and often display sentinel tags, hypertrophied anal papillae, or exposure of the internal sphincter muscle fibers, may require more targeted interventions.

The primary indication for lateral internal sphincterotomy is the presence of a chronic anal fissure that has failed to heal despite optimal non-surgical therapy. Additional indications can include:

- Recurrent anal fissures after initial healing

- Persistent pain or bleeding that affects daily activities

- Fissures associated with increased sphincter tone, confirmed via clinical or manometric assessment

Typically, patients are first offered less invasive options, but when these measures do not provide relief, sphincterotomy is considered.

Pathophysiology

The underlying problem in chronic anal fissures is often hypertonicity and spasm of the internal anal sphincter. This leads to decreased blood flow, impaired healing, and perpetuation of the fissure. The rational basis for sphincterotomy is to reduce the resting pressure of the internal anal sphincter, thereby improving blood supply and promoting fissure healing.

Types of Sphincterotomy

There are two main types of internal sphincterotomy:

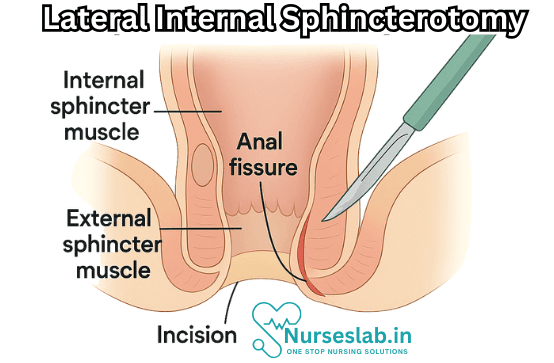

- Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy: The incision is made on the lateral aspect (usually the left side) of the internal anal sphincter.

- Posterior Internal Sphincterotomy: The incision is made at the posterior midline; however, this approach is less preferred due to increased risk of incontinence and poor wound healing in the posterior midline.

The lateral internal sphincterotomy is favored for its lower complication rate.

Contraindications

Certain conditions may preclude the use of lateral internal sphincterotomy, such as:

- Pre-existing anal incontinence

- Inflammatory bowel disease (especially Crohn’s disease affecting the anus)

- Coagulopathy or inability to tolerate anesthesia

- Active infection in the anorectal region (e.g., abscess)

Procedure Overview

Lateral internal sphincterotomy is performed under either local, regional, or general anesthesia depending on patient and surgeon preference.

Preoperative Preparation

Patients may be asked to fast for a certain period and undergo basic blood tests. Adequate bowel preparation may be recommended, though this varies by institution.

Surgical Technique

The procedure can be performed using either the open or closed technique:

- Open Technique: A small incision is made at the left lateral aspect of the anal verge. The internal sphincter is identified, carefully isolated, and a portion of its fibers (usually 1/3 to 1/2 the thickness) is divided. The wound is left open to heal by secondary intention or closed with absorbable sutures.

- Closed Technique: A small scalpel is inserted through a tiny skin incision, and the internal sphincter is divided blindly using tactile feedback. This method creates less external trauma but requires expertise to avoid injury to adjacent structures.

Throughout the procedure, meticulous attention is paid to avoid damaging the external sphincter and preserving continence.

Postoperative Care

Recovery from lateral internal sphincterotomy is generally swift, with most patients resuming daily activities within a few days. Postoperative care includes:

- Pain management, often with simple analgesics

- Prescribing stool softeners to minimize trauma to the healing area

- Maintenance of local hygiene via sitz baths and gentle cleaning

- Monitoring for signs of infection or bleeding

Most patients experience significant pain relief within 24–48 hours of surgery.

Complications and Risks

While lateral internal sphincterotomy is considered safe and effective, as with any surgical intervention, complications can arise:

- Infection: Local wound infection or abscess formation.

- Bleeding: Usually minor and self-limiting but can occasionally require intervention.

- Fecal Incontinence: The most feared complication. Incidence is generally low (temporary incontinence for flatus or stool in less than 10% of cases; persistent incontinence is rare).

- Recurrence of Fissure: A small percentage of patients may experience fissure recurrence, necessitating further management.

- Urinary Retention: Particularly in older individuals or those with underlying urological issues.

Outcomes and Effectiveness

Numerous studies and decades of clinical experience validate the efficacy of lateral internal sphincterotomy:

- Healing rates consistently exceed 90–95%, with most patients reporting dramatic symptom improvement and fissure resolution within weeks.

- Quality of life measures show marked improvement post-surgery, especially when compared to chronic suffering from fissures.

- Most patients can return to normal diet and activities quickly.

Long-term complications such as persistent incontinence are rare when the procedure is performed correctly and patient selection is judicious.

Alternatives to Surgery

Before recommending sphincterotomy, clinicians typically exhaust non-surgical options:

- Topical nitrates (e.g., nitroglycerin ointment)

- Calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem or nifedipine ointment)

- Botulinum toxin injection into the internal sphincter

- High-fiber diet, hydration, and stool softeners

- Sitz baths and topical anesthetics

For select patients, these can be effective. However, recalcitrant fissures often require surgical resolution.

Patient Selection and Counseling

Choosing the right candidate for lateral internal sphincterotomy is paramount. A thorough history and examination are essential, and patients should be counseled regarding:

- The nature and rationale of the procedure

- Risks and potential complications, especially incontinence

- Expected outcomes and postoperative recovery

- Available alternatives and the likelihood of their success

- Importance of follow-up care

Shared decision-making ensures that patients’ expectations are aligned with clinical reality.

Nursing Care of Patients Following Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy

The intervention aims to improve healing of the fissure, alleviate pain, and restore normal bowel function. Successful recovery from LIS requires diligent and holistic nursing care that encompasses physical, psychological, and educational support to optimize patient outcomes.

Immediate Postoperative Care

Monitoring Vital Signs and General Assessment

Vital Signs: Frequent monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation is essential, especially during the first 24 hours after surgery, to detect early signs of complications such as bleeding, infection, or adverse reactions to anesthesia.

Neurological Assessment: Evaluate level of consciousness and response to stimuli, particularly in patients who underwent general anesthesia or sedation.

Pain Management

Assessment: Pain is a significant concern following LIS. Use standardized pain scales (such as the Numeric Rating Scale or Visual Analog Scale) to assess severity, location, and characteristics.

Interventions:

- Administer prescribed analgesics, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen as appropriate.

- Educate patients about the importance of communicating pain intensity for timely management.

- Encourage use of warm sitz baths (20 minutes, 2-3 times daily) to soothe the surgical area, relieve pain, and promote circulation.

Wound Management

Inspection: Regularly inspect the surgical site for signs of bleeding, hematoma, swelling, or discharge. Document findings and notify the physician of abnormalities.

Dressing Care:

- Maintain cleanliness and dryness of the wound area.

- Use sterile technique when changing dressings to prevent infection.

- Monitor for signs of infection: redness, warmth, swelling, purulent discharge, fever.

Prevention of Infection

- Hygiene: Instruct patients to gently cleanse the perianal area after bowel movements using unscented, moistened wipes or warm water. Avoid harsh soaps or vigorous scrubbing.

- Antibiotics: Administer prophylactic antibiotics if prescribed and monitor for allergic reactions.

- Education: Teach patients about symptoms of infection and the importance of early reporting.

Bowel Management

Promotion of Soft Stools

Straining during defecation may disrupt wound healing and increase pain. Nurses should:

- Encourage a high-fiber diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes.

- Promote adequate hydration (at least 1.5-2 liters per day, unless contraindicated).

- Administer stool softeners or gentle laxatives as prescribed to prevent constipation.

Bowel Training

- Educate patients on regular bowel habits, responding promptly to the urge to defecate.

- Discourage prolonged sitting or straining on the toilet.

Prevention and Management of Complications

Bleeding

Minor bleeding may occur postoperatively; however, persistent or excessive bleeding requires prompt evaluation. Nurses should:

- Monitor dressings for fresh blood and quantify any bleeding.

- Observe for signs of hypovolemia (tachycardia, hypotension, dizziness).

- Report abnormalities immediately to the surgical team.

Infection

- Monitor for fever, increasing pain, foul-smelling wound discharge, or systemic symptoms.

- Reinforce the importance of wound care and perianal hygiene.

Incontinence

Transient minor incontinence may occur due to temporary sphincter weakness; persistent or severe incontinence should be promptly assessed.

- Monitor for involuntary leakage of stool or flatus.

- Document episodes and communicate with the surgical team.

- Offer reassurance and education regarding expected recovery.

Delayed Healing or Fissure Recurrence

- Assess for persistent pain, bleeding, or non-healing wound after the expected recovery period.

- Support adherence to dietary and bowel management strategies to reduce recurrence risk.

Patient Education and Psychosocial Support

Discharge Instructions

Provide comprehensive instructions regarding:

- Medication administration, including analgesics, antibiotics, and stool softeners.

- Wound care techniques and frequency of dressing changes.

- Signs and symptoms of complications requiring immediate medical attention.

- Follow-up appointments and when to seek urgent care.

Lifestyle Modifications

Advise on adopting habits that promote healing and prevent recurrence:

- Maintaining a balanced diet and proper hydration.

- Avoiding heavy lifting or strenuous activities for several weeks.

- Resuming gentle physical activity as tolerated to aid overall recovery.

Psychological Support

Recognize that anal fissures and surgical interventions can be distressing, causing anxiety or embarrassment.

- Offer empathetic support and active listening.

- Address concerns about bowel function, pain, or incontinence.

- Refer to counseling or support groups if needed.

Follow-up Care and Long-Term Outcomes

Follow-Up Visits: Reinforce the importance of scheduled appointments for wound assessment, monitoring healing, and timely intervention for complications.

Chronic Management: For patients with risk factors for recurrence (e.g., chronic constipation or underlying gastrointestinal disorders), ongoing education and preventative strategies are crucial.

Documentation and Communication

Accurate Record Keeping: Nurses must document all observations, interventions, and patient responses in detail to ensure continuity of care.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Regular communication with surgeons, dietitians, and other members of the healthcare team is essential for comprehensive management.

REFERENCES

- Keef KD, Cobine CA. Control of Motility in the Internal Anal Sphincter., https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6474703/. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019 Apr 30;25(2):189-204.

- Acar T, Acar N, Güngör F, et al. Treatment of chronic anal fissure: Is open lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) a safe and adequate option?. Asian J Surg. 2019;42(5):628-633. doi:10.1016/j.asjsur.2018.10.001

- HealthDirect (AU). Lateral internal sphincterotomy. https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/surgery/lateral-internal-sphincterotomy).

- Salih AM. Chronic anal fissures: Open lateral internal sphincterotomy result; a case series study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;15:56-58. DOI: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.02.005

- Lu Y, Lin A. Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33591347/). JAMA. 2021;325(7):702.

- MyHealth.Alberta.ca. Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy: Before Your Surgery. https://myhealth.alberta.ca/Health/aftercareinformation/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=ud128.

- Villanueva Herrero JA, Henning W, Sharma N, et al. Internal Anal Sphincterotomy., https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493213/. 2022 Oct 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

- Elias AW, Albert MR. Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021 Aug 1;64(8):e471. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002125. PMID: 34214059; PMCID: PMC8257469.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.