Capillary Leak Syndrome (CLS) is a rare, potentially life-threatening disorder characterized by recurrent episodes in which blood plasma leaks from small blood vessels (capillaries) into surrounding tissues. This process results in a sharp drop in blood pressure, swelling (edema), hemoconcentration (thickening of the blood), and a host of systemic complications. Though rare, awareness and understanding of Capillary Leak Syndrome are vital given the gravity of its presentation and the complexity of its management.

What is Capillary Leak Syndrome?

Capillary Leak Syndrome, also known as Clarkson’s disease or systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS), was first described by Dr. Bayard Clarkson in 1960. The condition is characterized by transient, unpredictable episodes during which the endothelial lining of capillaries becomes abnormally permeable. As a result, plasma – but not the cellular components of blood – leaks into interstitial spaces, causing sudden and severe shifts in fluid balance.

Pathophysiology

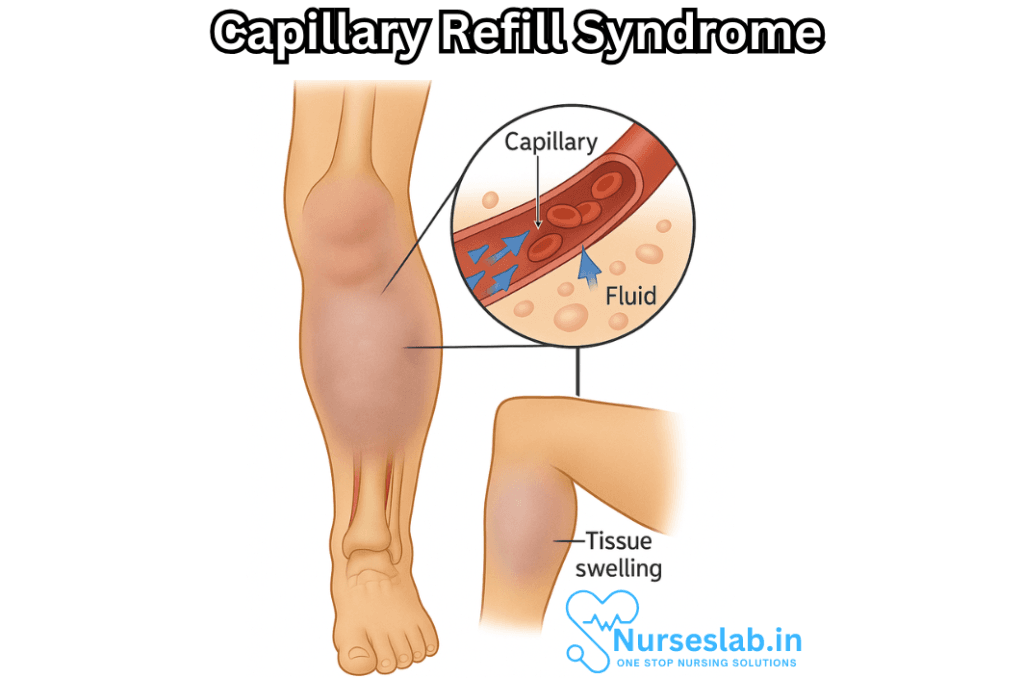

The precise mechanisms underlying Capillary Leak Syndrome remain incompletely understood. In healthy individuals, the endothelium (the thin layer of cells lining blood vessels) acts as a selective barrier, allowing the regulated passage of nutrients, electrolytes, and fluids. In CLS, this barrier becomes compromised, leading to the unchecked movement of plasma.

Several theories exist regarding the cause of this hyperpermeability. Some research suggests an immune-mediated process, possibly involving inflammatory cytokines and mediators that disrupt the tight junctions between endothelial cells. Others propose that monoclonal immunoglobulins, present in many patients with CLS, may play a direct or indirect role in endothelial dysfunction.

Types of Capillary Leak Syndrome

CLS can be broadly divided into two categories:

- Primary Capillary Leak Syndrome (SCLS or Clarkson’s Disease): This is an idiopathic form, meaning its exact cause is unknown. It typically occurs in adults and tends to be recurrent.

- Secondary Capillary Leak Syndrome: This form is associated with other conditions, such as sepsis, severe infections, certain medications (like interleukin-2 therapy for cancer), or autoimmune diseases.

The clinical course, management, and prognosis may differ depending on the type.

Clinical Presentation

Capillary Leak Syndrome is characterized by three distinct phases during an acute episode:

1. Prodromal Phase

Many patients report flu-like symptoms, such as fatigue, lightheadedness, nausea, muscle aches, or mild edema. This phase may precede the acute leak by several hours or days and can act as an early warning sign.

2. Leak Phase

This is the most dangerous phase, often lasting from several hours up to three days. There is a sudden and massive leakage of plasma from the blood vessels into surrounding tissues. Key features include:

- Rapid hypotension: A steep drop in blood pressure, sometimes leading to shock.

- Hemoconcentration: Elevated hematocrit and hemoglobin levels due to loss of plasma volume.

- Hypoalbuminemia: Markedly decreased levels of albumin in the blood.

- Edema: Generalized body swelling, often most pronounced in the limbs.

- Organ dysfunction: The decreased perfusion can lead to kidney failure, confusion, or even cardiac arrest.

3. Recovery (Post-Leak) Phase

During recovery, the previously leaked fluid re-enters the bloodstream, which can cause sudden fluid overload, pulmonary edema, and potentially congestive heart failure, unless carefully managed.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Capillary Leak Syndrome can be extremely challenging due to its rarity and similarity to other, more common conditions. There is no single diagnostic test. Physicians rely on a combination of clinical findings and laboratory data, especially during an acute attack:

- Triad of hypotension, hemoconcentration, and hypoalbuminemia without an obvious cause (such as sepsis, trauma, or anaphylaxis)

- Exclusion of other causes: ruling out sepsis, severe allergic reactions, and other forms of shock

- History of recurrent episodes with similar features

- Presence of monoclonal gammopathy (detected in many cases)

Imaging studies may demonstrate edema but are non-specific.

Differential Diagnosis

Because CLS mimics many other conditions, especially at presentation, it is important to distinguish it from:

- Septic shock

- Anaphylactic shock

- Angioedema

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Congestive heart failure

Detailed history and laboratory analysis are crucial for making the correct diagnosis.

Treatment and Management

No cure currently exists for Capillary Leak Syndrome, and management focuses on supportive care during acute episodes and preventive strategies between attacks.

Acute Episode Management

The immediate priorities are stabilizing blood pressure and organ function:

- Fluid resuscitation: Intravenous fluids are given cautiously to maintain blood pressure, but excessive fluids can worsen the post-leak phase.

- Vasopressors: Medications may be required to support blood pressure if fluids alone are insufficient.

- Close monitoring: Intensive care is often necessary to track vital signs, urine output, and signs of organ dysfunction.

- Treatment of complications: Addressing acute kidney injury, pulmonary edema, or arrhythmias as they arise.

Long-term and Preventive Therapies

The goal is to prevent or reduce the frequency of attacks:

- IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin): Regular monthly infusions have shown success in reducing both the frequency and severity of attacks in many patients.

- Beta-agonists and theophylline: These medications may help stabilize the endothelium in some individuals, though evidence is mixed.

- Avoidance of triggers: Any known precipitants, such as infections or certain medications, should be minimized.

Research into new treatments and understanding the underlying causes is ongoing. Some patients with secondary CLS may improve if the underlying condition is treated.

Prognosis

The outlook for patients with Capillary Leak Syndrome varies. Some individuals experience only a single episode, while others have recurrent, life-threatening attacks. The mortality rate is high during severe episodes, especially if diagnosis and treatment are delayed.

With early recognition and appropriate preventive treatment, the prognosis improves, and many individuals can lead near-normal lives between episodes.

Living with Capillary Leak Syndrome

- For those diagnosed with CLS, long-term management is multidimensional:

- Participation in patient support groups, both for information and community

- Regular follow-up with a physician experienced in rare diseases

- Education about early warning signs and when to seek emergency care

- Carrying a medical alert bracelet or identification

- Psychological support, as rare diseases can carry an emotional burden

Nursing Care of Patients with Capillary Leak Syndrome

Based on the acute onset and the risks associated with the syndrome, nursing care plays a pivotal role in monitoring, supporting, and managing patients throughout the course of the illness.

Assessment and Monitoring

Initial Assessment

- Obtain thorough patient history, including any triggers (recent infections, medications, or underlying diseases)

- Baseline vital signs: blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, oxygen saturation

- Assessment of fluid status: edema, weight changes, urine output

- Review laboratory results for hemoconcentration (increased hematocrit), low albumin, renal function tests, and electrolytes

Ongoing Monitoring

- Frequent monitoring of vital signs, especially blood pressure and heart rate

- Strict input and output charting

- Daily weights to evaluate fluid shifts

- Continuous assessment for signs of hypoperfusion (cold, clammy skin, altered mental status, decreased urine output)

- Monitor central venous pressure (if central line is available) for intravascular volume status

- Observe for respiratory distress or pulmonary edema, particularly during fluid reabsorption phase

- Regular review of laboratory results to monitor hemoconcentration, electrolytes, renal and liver function

Interventions

Acute Phase Interventions

Fluid Resuscitation:

- Administer intravenous fluids as prescribed, usually isotonic saline or albumin, to maintain blood pressure and organ perfusion

- Monitor for signs of fluid overload, especially in patients with cardiac or renal compromise

- Use of vasopressors may be necessary under medical guidance for refractory hypotension

Monitoring and Support:

- Continuous cardiac monitoring for arrhythmias or ischemia

- Supplemental oxygen or ventilatory support if required

- Insertion of urinary catheter for accurate urine output assessment

- Prevention of complications such as pressure ulcers, deep vein thrombosis and infections

Medication Management:

- Administer medications as prescribed, which may include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, or other immunomodulatory agents

- Ensure timely delivery and monitor for side-effects

- Monitor and administer prophylactic anticoagulation if indicated, balancing risk of bleeding

Transition and Recovery Phase

As the capillary barrier function returns and fluid re-enters the vascular space, focus shifts to managing potential complications of fluid overload.

- Adjust fluid therapy as per medical direction; diuretics may be prescribed to prevent pulmonary edema

- Monitor for signs of overload: crackles on lung auscultation, rising blood pressure, jugular venous distension, worsening edema

- Continue strict input/output and daily weights

- Assess for electrolyte disturbances and manage accordingly

- Support nutrition, as patients may be catabolic and hypoalbuminemic

Complication Prevention and Management

Hypovolemic Shock

- Early recognition of shock symptoms is critical (tachycardia, low BP, cold extremities, altered consciousness)

- Prompt resuscitation with fluids and vasopressors as advised

- Maintain close observation and readiness for rapid interventions

Acute Kidney Injury

- Monitor urine output and renal function tests closely

- Prevent nephrotoxic exposures and adjust medication dosages

- Early nephrology input may be required in severe cases

Pulmonary Edema

- Be vigilant during the recovery phase for signs of pulmonary congestion and respiratory compromise

- Initiate oxygen therapy and diuretics as appropriate

- Support airway and breathing as needed, including escalation to non-invasive or invasive ventilation

Thromboembolism

- Apply mechanical or pharmacologic prophylaxis for DVT, as tolerated

- Encourage early mobilization as soon as feasible

Patient Comfort and Psychosocial Support

Capillary Leak Syndrome and the associated interventions can be distressing for both patients and families.

- Provide emotional support, reassurance, and clear communication regarding diagnosis, progress, and prognosis

- Involve family in care planning and education

- Ensure adequate pain and symptom control

- Maintain privacy and dignity in all care activities

- Facilitate rest and sleep by minimizing unnecessary disturbances

Patient and Family Education

Education is crucial for effective self-care and early identification of recurrence or complications.

- Explain the disease process, expected course, and warning signs that require urgent attention

- Provide written and verbal instructions regarding medication use, fluid management, and when to seek help

- Encourage adherence to follow-up appointments and lab monitoring

- Inform about lifestyle measures to reduce infection risk and promote general health

Discharge Planning and Follow-Up

Planning for discharge requires a multidisciplinary approach.

- Ensure stability of vital signs and resolution of acute issues before discharge

- Arrange for home health support if mobility or self-care is compromised

- Coordinate with primary care providers and specialists for follow-up care

- Provide contact information for urgent concerns

REFERENCES

- Druey KM, Arnaud L, Parikh SM. Systemic capillary leak syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024 Nov 14;10(1):86. doi: 10.1038/s41572-024-00571-5. PMID: 39543164.

- Alkunaizi AM, Kabbani AH, ElTigani MA. Chronic idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome: a case report. https://aacijournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13223-019-0347-0. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2019;15:34.

- Ebdrup L, Druey K, Mogensen TH. Severe capillary leak syndrome with cardiac arrest triggered by influenza viral infection. https://casereports.bmj.com/content/casereports/2018/bcr-2018-226108.full.pdf. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Aug. [PDF].

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Systemic capillary leak syndrome. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/1084/systemic-capillary-leak-syndrome.

- Khan HR, Khan S, Srikanth A, Smith WHT. A case report of capillary leak syndrome with recurrent pericardial and pleural effusions. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7180544/. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020 Jun;4(2):1-5.

- Cheung PC, et al. (2021). Fatal exacerbations of systemic capillary leak syndrome complicating coronavirus disease.

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/27/10/21-1155_article - Systemic capillary leak syndrome. (2021).

https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/1084/systemic-capillary-leak-syndrome - Siddall E, Khatri M, Radhakrishnan J. Capillary leak syndrome: etiologies, pathophysiology, and management. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28318633/. Kidney Int. 2017 Jul;92(1):37-46.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.