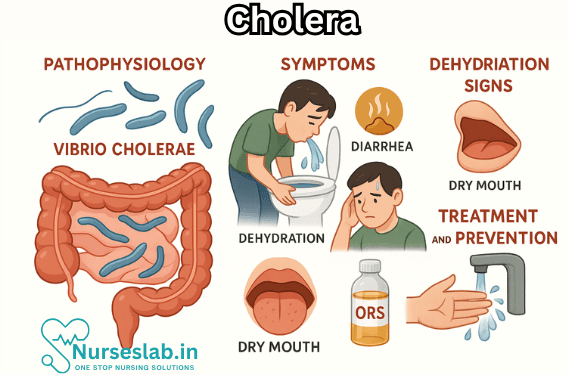

Cholera is an acute diarrheal illness caused by Vibrio cholerae, typically spread through contaminated water or food. It can lead to rapid dehydration and requires prompt rehydration and public‑health measures to prevent outbreaks.

Introduction

Cholera is a severe, acute diarrhoeal disease caused by infection with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It remains a significant public health issue, especially in regions with inadequate access to clean water and sanitation. Cholera can cause large outbreaks and, if left untreated, can lead to death within hours due to rapid dehydration. Despite being preventable and treatable, cholera continues to affect millions of people worldwide, particularly in developing countries.

Historical Perspective

Cholera has been known for centuries, with descriptions of symptoms resembling cholera dating back to ancient Sanskrit texts from India. The disease became globally recognised in the 19th century, following a series of pandemics that began in the Indian subcontinent and spread across the world. The first cholera pandemic started in 1817 in the Ganges Delta and rapidly extended to Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. Since then, there have been seven major pandemics, the most recent of which began in 1961 and continues today, primarily affecting regions in Africa and Asia.

Aetiology and Microbiology

Cholera is caused by the Gram-negative, comma-shaped bacterium Vibrio cholerae. There are over 200 serogroups of V. cholerae, but only serogroups O1 and O139 are known to cause epidemic and pandemic cholera. The O1 serogroup is further classified into two biotypes: Classical and El Tor, and each biotype is subdivided into two serotypes: Inaba and Ogawa. The O139 serogroup, first identified in Bangladesh and India in 1992, has also been responsible for outbreaks.

The pathogenicity of V. cholerae is primarily due to the production of cholera toxin (CT), an enterotoxin that disrupts the normal function of the intestinal lining, leading to profuse watery diarrhoea.

Epidemiology

Cholera is endemic in many parts of the world, particularly in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Latin America. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are 1.3 to 4.0 million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths due to cholera each year globally.

Transmission occurs through the faeco-oral route, primarily via ingestion of contaminated water or food. Outbreaks are often associated with poor sanitation, lack of clean drinking water, overcrowding, and natural disasters that disrupt water and sanitation infrastructure. Children and immunocompromised individuals are at higher risk of severe disease.

Seasonality is notable in cholera epidemiology, with cases often peaking during and after the monsoon season in endemic regions, due to flooding and contamination of water sources.

Pathogenesis

After ingestion, V. cholerae passes through the acidic environment of the stomach and colonises the small intestine. The bacterium attaches to the mucosal surface using pili and secretes cholera toxin. The toxin consists of two subunits: A and B. The B subunit binds to the GM1 ganglioside receptors on enterocytes, facilitating entry of the A subunit, which activates adenylate cyclase. This leads to increased cyclic AMP (cAMP) in the cells, causing massive secretion of chloride ions and water into the intestinal lumen, resulting in the characteristic copious, watery diarrhoea known as “rice-water stools”.

Clinical Features

The incubation period for cholera is typically short, ranging from a few hours to five days, most commonly two to three days. The clinical manifestations vary depending on the severity of infection.

- Asymptomatic Infection: Most infections are mild or asymptomatic, but the infected individual can still shed the bacteria in stool and contribute to transmission.

- Mild to Moderate Disease: Presents as mild diarrhoea and vomiting without signs of dehydration.

- Severe Cholera: Characterised by sudden onset of profuse, painless, watery diarrhoea (“rice-water stools”), vomiting, and rapid dehydration. Patients may lose up to 1 litre of fluid per hour. Signs of dehydration include sunken eyes, dry mouth, decreased skin turgor, hypotension, tachycardia, and oliguria or anuria. Severe cases can progress to hypovolaemic shock and death within hours if not treated promptly.

Other symptoms may include muscle cramps due to electrolyte loss and, in children, hypoglycaemia and seizures.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of cholera is primarily clinical in the context of an outbreak or in endemic areas, especially in patients presenting with acute, watery diarrhoea and dehydration. Laboratory confirmation is essential for surveillance and outbreak management.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

- Stool Culture: The gold standard for diagnosis. V. cholerae can be isolated from fresh stool or rectal swabs using selective media such as thiosulphate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar. The colonies are further confirmed by biochemical tests and serotyping.

- Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs): Immunochromatographic tests are available for quick detection but are less sensitive than culture.

- Molecular Techniques: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) can be used for rapid and specific identification.

Other Investigations: Assessment of electrolyte levels, renal function, and blood glucose may be necessary in severe cases to guide management.

Management

Cholera is a medical emergency that requires prompt and aggressive treatment to prevent mortality. The mainstay of therapy is rehydration, with adjunctive use of antibiotics in specific cases.

Rehydration Therapy

Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT): For most patients, oral rehydration solution (ORS) is sufficient. The WHO-recommended ORS contains the correct balance of glucose and electrolytes to facilitate absorption in the intestine.

- Adults: 200–400 ml/kg of ORS in the first 24 hours.

- Children: 50–100 ml/kg of ORS in the first 4 hours, then as needed.

Intravenous (IV) Fluids: Indicated in cases of severe dehydration or when the patient is unable to tolerate oral fluids due to persistent vomiting or shock. Ringer’s lactate is preferred due to its balanced electrolyte composition.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are recommended for patients with moderate to severe cholera to reduce the duration of diarrhoea and limit bacterial shedding. Commonly used antibiotics include:

- Doxycycline (single dose for adults)

- Azithromycin (especially in children and pregnant women)

- Ciprofloxacin and tetracycline (depending on sensitivity patterns)

Antibiotic resistance is an emerging concern, making local susceptibility testing important.

Supportive Care

Additional management includes correction of hypoglycaemia (especially in children), potassium supplementation, and monitoring for complications such as acute kidney injury.

Complications

If not treated promptly, cholera can lead to several life-threatening complications:

- Severe dehydration and hypovolaemic shock

- Electrolyte imbalances: Particularly hypokalaemia and metabolic acidosis

- Renal failure: Due to sustained hypotension and hypoperfusion

- Hypoglycaemia: Especially in children and malnourished patients

- Death: Mortality can be as high as 50% in untreated severe cases, but with adequate rehydration, it drops below 1%

Prevention and Control

Effective prevention and control of cholera depend on a multi-pronged approach targeting the source of infection, transmission routes, and susceptible populations.

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH)

- Ensuring access to safe drinking water by treating and regularly testing water supplies.

- Promoting the use of sanitary latrines and proper disposal of human waste.

- Encouraging handwashing with soap, especially after defecation and before handling food.

- Food safety measures, such as thorough cooking and safe storage.

Vaccination

Oral cholera vaccines (OCVs) are available and recommended for use in endemic areas, during outbreaks, and for high-risk populations. Currently, three WHO-prequalified OCVs are in use: Dukoral, Shanchol, and Euvichol-Plus.

- Dukoral: Requires two doses, protects against O1 serogroup, also contains recombinant B subunit of cholera toxin.

- Shanchol and Euvichol-Plus: Two doses, protect against both O1 and O139 serogroups.

Vaccination is an adjunct to, not a replacement for, improvements in water and sanitation.

Surveillance and Outbreak Response

- Community education on recognising symptoms and seeking prompt care.

- Early detection and reporting of cases to local and national health authorities.

- Rapid investigation and response teams to contain outbreaks.

- Establishment of cholera treatment centres during epidemics.

Nursing Care of Patients with Cholera

Nursing care for patients with cholera is crucial, as it forms the backbone of recovery and prevention of complications.

Assessment of the Cholera Patient

Initial Assessment

Upon admission or presentation, nursing assessment should include:

- Vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature)

- Level of dehydration (mild, moderate, severe)

- Physical examination (skin turgor, sunken eyes, dry mucous membranes, rapid pulse, low blood pressure)

- Intake and output monitoring

- Observation for signs of complications (muscle cramps, reduced urine output, confusion, shock)

Ongoing Assessment

- Regular monitoring of vital signs

- Continuous assessment of hydration status

- Review of electrolyte levels (if possible)

- Documentation of stool and vomitus volume and characteristics

- Evaluation for effectiveness of rehydration therapy

Fluid and Electrolyte Management

The mainstay of cholera management is prompt rehydration. Fluid replacement can be oral or intravenous, depending on the severity of dehydration.

Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT)

- Indicated for mild to moderate dehydration

- Use of Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS) solution is recommended

- Encourage small, frequent sips of ORS after each stool or vomiting episode

- Continue breastfeeding or normal feeding in children

Intravenous (IV) Fluid Therapy

- Indicated in cases of severe dehydration or if the patient is unable to tolerate oral fluids

- Ringer’s lactate is preferred for IV replacement

- Monitor for signs of fluid overload, especially in children and the elderly

- Monitor electrolyte levels and replace potassium as needed

Monitoring and Evaluation

- Assess for improvement in skin turgor, moist mucous membranes, and urine output

- Monitor for resolution of symptoms and prevention of complications

- Document all interventions and patient responses

Infection Control and Prevention

Cholera is highly contagious, and strict infection control measures are essential to prevent its spread.

Isolation and Barrier Nursing

- Isolate the patient in a designated area or ward

- Use gloves and aprons when handling patients or contaminated materials

- Practice proper hand hygiene before and after all patient contact

- Dispose of excreta and contaminated items safely (use of disinfectants)

Environmental Hygiene

- Ensure availability of clean potable water

- Disinfect patient areas regularly

- Promote safe disposal of waste and excreta

- Educate family and caregivers on hygiene practices

Nutritional Support

Patients with cholera often refuse food due to vomiting and discomfort, but nutritional support is vital, especially for children and vulnerable populations.

- Encourage the patient to eat as soon as vomiting stops

- Continue breastfeeding for infants

- Offer easily digestible, energy-rich foods

- Monitor for signs of malnutrition

Symptom Management

- Administer antiemetics if prescribed for severe vomiting

- Provide skin care to prevent breakdown due to frequent diarrhea

- Maintain perineal hygiene

- Regularly change bed linen and clothing

- Control fever with antipyretics if needed

Patient and Family Education

Comprehensive health education is integral to nursing care, aiming to prevent recurrence and reduce community spread.

Key Educational Topics

- Importance of handwashing with soap and clean water

- Safe food and water practices (boiling water, washing fruits and vegetables, eating food while still hot)

- Recognizing early symptoms of dehydration and seeking medical help promptly

- Proper disposal of stool and other contaminated materials

- Vaccination information if available and recommended

Psychosocial Support

Cholera can be a frightening disease, both for the patient and their family. Nurses play an important role in providing reassurance, reducing anxiety and addressing the psychological impact of isolation.

- Offer emotional support and clear communication about the disease and its treatment

- Facilitate contact with family members where possible, even during isolation

- Involve family in the care process as appropriate

Complication Management

Nurses must be vigilant for the development of complications and respond promptly:

- Monitor for signs of hypovolemic shock (rapid weak pulse, cold extremities, low blood pressure)

- Monitor urine output for signs of renal failure

- Watch for persistent vomiting or inability to retain fluids

- Alert the medical team promptly if complications are suspected

Discharge Planning and Follow-Up

Proper discharge planning ensures that patients continue to recover and do not transmit cholera to others.

- Assess readiness for discharge (resolution of symptoms, adequate hydration, normal eating and drinking)

- Review home care instructions with the patient and family

- Arrange for community health follow-up if needed

- Provide information about signs of recurrence or complications

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). About Cholera. https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/about/index.html. Updated 5/12/2024.

- Chowdhury F, Ross AG, Islam MT, McMillan NAJ, Qadri F. Diagnosis, Management, and Future Control of Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2022 Sep 21;35(3):e0021121. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00211-21. Epub 2022 Jun 21.

- Clemens JD, Nair GB, Ahmed T, Qadri F, Holmgren J. Cholera. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28302312/. Lancet. 2017 Sep 23;390(10101):1539-1549.

- Cholera. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera.

- Montero DA, Vidal RM, Velasco J, George S, Lucero Y, Gómez LA, Carreño LJ, García-Betancourt R, O’Ryan M. Vibrio cholerae, classification, pathogenesis, immune response, and trends in vaccine development. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 May 5;10:1155751. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1155751

- Waldor MK, Ryan ET. Cholera and Other Vibrioses. In: Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 21st ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2022.

- Kimberlin DW, et al. Cholera (Vibrio cholerae). In: Red Book: 2021–2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 32nd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2022.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.