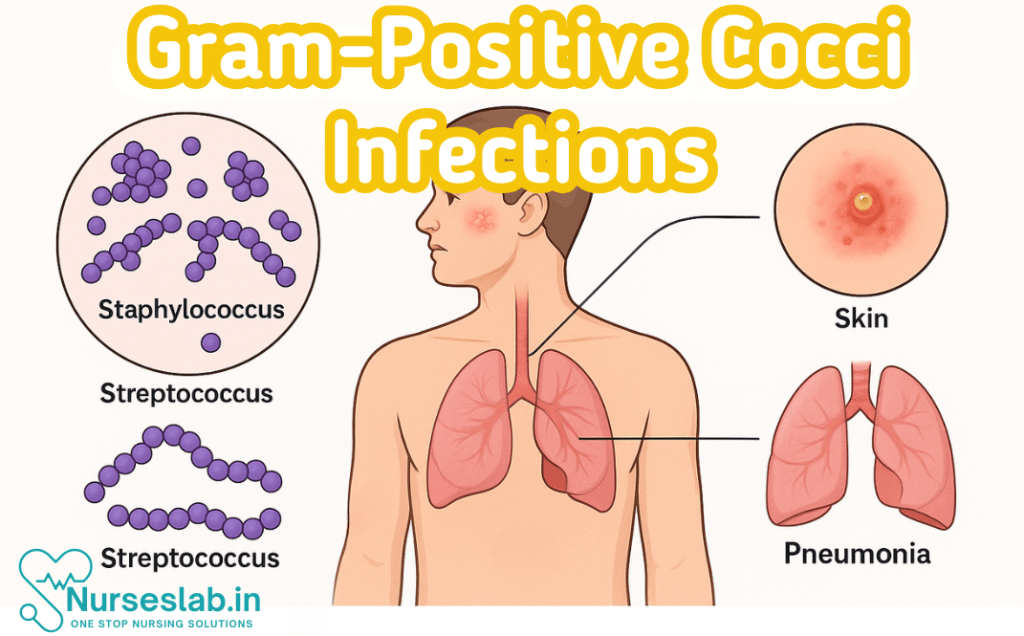

Gram-positive cocci are round-shaped bacteria that retain crystal violet stain due to thick peptidoglycan walls. Common genera include Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, associated with skin, respiratory, and systemic infections—key in clinical microbiology and nursing care.

Introduction

Gram positive cocci constitute a significant group of bacteria responsible for a broad spectrum of human infections. Their clinical relevance spans from mild skin infections to life-threatening systemic diseases. Recognising and managing these pathogens is a cornerstone of clinical microbiology and infectious disease practice.

Definition and Importance

Gram positive cocci are spherical bacteria that retain the crystal violet stain during Gram staining due to their thick peptidoglycan cell wall. They are distinguished by their morphology, arrangement, and biochemical properties. These organisms are ubiquitous in nature and form part of the normal human flora, but under certain circumstances, can cause a wide array of infections. Their clinical importance is underscored by their prevalence, potential for severe disease, and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

Overview of Gram-Positive Cocci

Gram positive cocci are broadly classified into several genera, of which Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus are the most medically significant. Other less commonly encountered genera include Micrococcus and Peptostreptococcus. Each genus exhibits distinct morphological, biochemical, and pathogenic characteristics, which are pivotal for accurate identification and management.

Classification of Gram Positive Cocci

Classification is based on several parameters including cellular arrangement, catalase reaction, haemolytic patterns, and other biochemical tests.

- Staphylococcus: Arranged in clusters, catalase positive

- Streptococcus: Arranged in chains or pairs, catalase negative

- Enterococcus: Similar to streptococci, but with unique biochemical and resistance profiles

- Others: Includes Micrococcus (tetrads) and Peptostreptococcus (anaerobic)

Key Characteristics

| Genus | Arrangement | Catalase | Haemolysis | Clinical Significance |

| Staphylococcus | Clusters | Positive | Variable | Skin, soft tissue, systemic infections |

| Streptococcus | Chains/pairs | Negative | Alpha, beta, gamma | Pharyngitis, pneumonia, sepsis, endocarditis |

| Enterococcus | Pairs/short chains | Negative | Gamma (non-haemolytic) | Urinary tract, intra-abdominal, endocarditis |

| Micrococcus | Tetrads/clusters | Positive | Non-haemolytic | Rarely pathogenic |

| Peptostreptococcus | Chains | Negative | Non-haemolytic | Anaerobic infections |

Staphylococcus Infections

Overview

The genus Staphylococcus comprises several species, among which Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus are most clinically relevant. These organisms are part of the normal flora but can become opportunistic pathogens under suitable conditions.

Staphylococcus aureus

Clinical Features

- Skin and soft tissue infections: boils, abscesses, cellulitis, impetigo

- Musculoskeletal: osteomyelitis, septic arthritis

- Respiratory: pneumonia (post-influenza, ventilator-associated)

- Cardiovascular: infective endocarditis, especially on damaged valves

- Toxin-mediated: toxic shock syndrome, scalded skin syndrome, food poisoning

- Systemic: bacteraemia, sepsis

Pathogenesis

S. aureus possesses an array of virulence factors, including surface proteins (adhesins), enzymes (coagulase, hyaluronidase), and toxins (hemolysins, leukocidins, superantigens). Its ability to form biofilms and evade immune responses contributes to persistent and recurrent infections. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) presents additional therapeutic challenges due to resistance.

Staphylococcus epidermidis

Clinical Features

- Device-associated infections: prosthetic joints, intravascular catheters, pacemakers

- Bacteraemia in immunocompromised hosts

Pathogenesis

S. epidermidis is notable for its biofilm-forming ability, particularly on indwelling medical devices. While less virulent than S. aureus, its resistance to multiple antibiotics, especially in healthcare settings, makes it a significant nosocomial pathogen.

Staphylococcus saprophyticus

Clinical Features

- Urinary tract infections, particularly in sexually active young women

Pathogenesis

This organism adheres to uroepithelial cells and is resistant to the high urea concentrations in urine, facilitating colonisation and infection.

Streptococcus Infections

Overview

The genus Streptococcus encompasses a diverse group classified by haemolysis (alpha, beta, gamma), Lancefield grouping, and biochemical properties. Medically important species include S. pyogenes (Group A), S. agalactiae (Group B), S. pneumoniae, and the viridans group.

Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus)

Clinical Features

- Pharyngitis (“strep throat”)

- Skin: impetigo, erysipelas, cellulitis, necrotising fasciitis

- Systemic: scarlet fever, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome

- Post-infectious sequelae: rheumatic fever, acute glomerulonephritis

Pathogenesis

Virulence factors include M protein, streptolysins, hyaluronidase, and exotoxins. The ability to evade phagocytosis and induce immune-mediated damage underlies many of its complications.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Clinical Features

- Respiratory: community-acquired pneumonia, otitis media, sinusitis

- Central nervous system: meningitis

- Bacteraemia, sepsis, particularly in asplenic or immunocompromised individuals

Pathogenesis

The polysaccharide capsule is the major virulence determinant, enabling evasion of host immunity. Pneumolysin and other toxins contribute to tissue damage and inflammation.

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus)

Clinical Features

- Neonatal: sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis (early and late onset)

- Adults: urinary tract infections, soft tissue infections, bacteremia, endocarditis (rare)

Pathogenesis

Colonises the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts. Vertical transmission during childbirth is a major route for neonatal infection. Capsule and surface proteins are key to virulence.

Viridans Group Streptococci

Clinical Features

- Dental caries

- Subacute bacterial endocarditis (especially in those with underlying heart disease)

- Occasional abscess formation

Pathogenesis

Low virulence but able to adhere to damaged heart valves and dental surfaces due to dextran production.

Enterococcus Infections

Overview

Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium are the most clinically significant species. Once classified as group D streptococci, these organisms are now recognised as a distinct genus due to unique biochemical and genetic traits.

Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium

Clinical Features

- Urinary tract infections (especially in hospitalised patients)

- Intra-abdominal and pelvic infections

- Bacteraemia and endocarditis

- Occasionally wound and soft tissue infections

Pathogenesis

Enterococci are notable for intrinsic resistance to many antibiotics and their ability to acquire new resistance genes, including vancomycin resistance (VRE). They form biofilms and persist in hospital environments, contributing to nosocomial outbreaks.

Other Gram Positive Cocci

Micrococcus

Micrococcus species are generally regarded as non-pathogenic or of low virulence. They are part of the normal skin flora and infrequently cause disease, typically in immunocompromised hosts or in association with indwelling devices.

Peptostreptococcus

Peptostreptococcus species are anaerobic, part of the normal flora of the mouth, gut, and genitourinary tract. They are implicated in mixed anaerobic infections, such as deep tissue abscesses, brain abscesses, and pelvic infections, particularly when mucosal barriers are breached.

Diagnosis

Gram Stain

Gram positive cocci appear as purple, spherical cells under the microscope following Gram staining. Arrangement (clusters, chains, pairs, tetrads) provides initial clues to genus.

Culture Techniques

- Blood agar: Differentiates Streptococcus (haemolysis patterns) and Staphylococcus (colony morphology)

- Selective media: Mannitol salt agar (Staphylococcus), bile esculin agar (Enterococcus)

Biochemical Tests

- Catalase test: Differentiates Staphylococcus (positive) from Streptococcus/Enterococcus (negative)

- Coagulase test: Differentiates S. aureus (positive) from other staphylococci

- Bacitracin sensitivity: S. pyogenes is sensitive

- Optochin sensitivity: S. pneumoniae is sensitive

- Bile solubility: S. pneumoniae is soluble

- PYR test: Group A Streptococcus and Enterococcus are positive

Molecular Methods

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are increasingly used for rapid and precise identification, detection of resistance genes (e.g., mecA for MRSA, vanA for VRE), and epidemiological typing.

Clinical Manifestations

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

- Impetigo, cellulitis, erysipelas, abscesses (S. aureus, S. pyogenes)

- Necrotising fasciitis (S. pyogenes, mixed infections including Peptostreptococcus)

Respiratory Infections

- Pharyngitis (S. pyogenes)

- Pneumonia (S. pneumoniae, S. aureus)

- Sinusitis, otitis media (S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes)

Cardiac Infections

- Endocarditis (S. aureus, viridans streptococci, Enterococcus, Peptostreptococcus in mixed infections)

Central Nervous System Infections

- Meningitis (S. pneumoniae, S. agalactiae in neonates, rarely S. aureus)

- Brain abscess (Peptostreptococcus, S. aureus, viridans group)

Systemic Infections

- Bacteraemia, sepsis (S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, Enterococcus)

- Toxic shock syndrome (S. aureus, S. pyogenes)

Treatment and Management

Antibiotic Therapy

Treatment is guided by organism identification, susceptibility profiles, infection site, and patient factors. Empiric therapy may be necessary pending laboratory results, but should be tailored once sensitivities are known.

- S. aureus: Beta-lactams (e.g., cloxacillin, cefazolin) for methicillin-sensitive strains; vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin for MRSA

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci: Vancomycin often required due to resistance

- S. pyogenes: Penicillin remains the drug of choice; alternatives include cephalosporins and macrolides

- S. pneumoniae: Penicillin or third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime); vancomycin for resistant strains

- Enterococcus: Ampicillin or vancomycin (plus gentamicin for synergy in endocarditis); linezolid, daptomycin for VRE

- Anaerobic cocci (Peptostreptococcus): Metronidazole, beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations, or clindamycin

Resistance Issues

- MRSA: Prevalence varies by region; requires use of non-beta-lactam agents

- VRE: Increasingly common in hospital settings; limits therapeutic options

- Macrolide and penicillin resistance: Noted among S. pneumoniae and S. pyogenes in some areas

Supportive Care

Management of severe infections may require surgical intervention (e.g., abscess drainage, debridement), haemodynamic support, and management of complications such as shock or organ dysfunction.

Prevention and Control

Infection Control Measures

- Hand hygiene and aseptic techniques in healthcare settings

- Contact precautions for MRSA and VRE carriers

- Surveillance and decolonisation strategies in high-risk units

Vaccines

- Effective polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines available for S. pneumoniae

- No vaccines currently for S. aureus, S. pyogenes, or Enterococcus, though research is ongoing

Public Health Measures

- Antimicrobial stewardship to limit resistance emergence

- Education of healthcare workers and the public

- Surveillance for nosocomial and community outbreaks

Gram Positive Cocci

| Species | Morphology & Arrangement | Biochemical Findings | Key Clinical Syndromes | Antibiotic Sensitivity |

| S. aureus | Clusters, golden colonies | Catalase +, Coagulase +, Mannitol fermenter | Skin/soft tissue, pneumonia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, sepsis, TSS | Sensitive: Cloxacillin, cefazolin. MRSA: Vancomycin, linezolid |

| S. epidermidis | Clusters, white colonies | Catalase +, Coagulase -, Novobiocin sensitive | Device-related infections, bacteraemia | Often resistant; vancomycin required |

| S. saprophyticus | Clusters | Catalase +, Coagulase -, Novobiocin resistant | UTI in young women | Usually sensitive to nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| S. pyogenes (GAS) | Chains | Catalase -, Bacitracin sensitive, PYR +, Beta-haemolytic | Pharyngitis, cellulitis, necrotising fasciitis, rheumatic fever | Penicillin sensitive |

| S. agalactiae (GBS) | Chains | Catalase -, CAMP +, Beta-haemolytic | Neonatal sepsis, meningitis | Penicillin sensitive |

| S. pneumoniae | Lancet-shaped diplococci | Catalase -, Optochin sensitive, Bile soluble, Alpha-haemolytic | Pneumonia, meningitis, otitis media | Penicillin/cephalosporin sensitive; resistance emerging |

| Viridans streptococci | Chains | Catalase -, Alpha-haemolytic, Optochin resistant | Endocarditis, dental caries | Generally penicillin sensitive |

| E. faecalis/faecium | Pairs/short chains | Catalase -, Bile esculin +, PYR +, Gamma-haemolytic | UTI, endocarditis, intra-abdominal infections | Ampicillin/vancomycin; VRE: linezolid, daptomycin |

| Micrococcus | Tetrads/clusters | Catalase +, Non-haemolytic | Rarely pathogenic | Generally sensitive to penicillins |

| Peptostreptococcus | Chains | Catalase -, Anaerobic growth | Brain, dental, deep tissue abscesses | Metronidazole, clindamycin, penicillin |

Conclusion

Gram positive cocci remain central to the aetiology of infectious diseases worldwide. Their diversity in clinical presentation, evolving resistance patterns, and potential for severe morbidity and mortality necessitate continued vigilance among clinicians and microbiologists. Accurate laboratory identification, appropriate antibiotic selection, and adherence to infection prevention practices are vital. Future directions include the development of novel antimicrobial agents, vaccines, and rapid diagnostic tools to address the challenges posed by these formidable pathogens.

REFERENCES

- Apurba S Sastry, Essential Applied Microbiology for Nurses including Infection Control and Safety, First Edition 2022, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-9354659386

- Joanne Willey, Prescott’s Microbiology, 11th Edition, 2019, Innox Publishers, ASIN- B0FM8CVYL4.

- Anju Dhir, Textbook of Applied Microbiology including Infection Control and Safety, 2nd Edition, December 2022, CBS Publishers and Distributors, ISBN: 978-9390619450

- Gerard J. Tortora, Microbiology: An Introduction 13th Edition, 2019, Published by Pearson, ISBN: 978-0134688640

- Durrant RJ, Doig AK, Buxton RL, Fenn JP. Microbiology Education in Nursing Practice. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2017 Sep 1;18(2):18.2.43. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5577971/

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.