Digestion and absorption of carbohydrates begin in the mouth with salivary amylase, continue in the small intestine with pancreatic enzymes, and end with glucose absorption into the bloodstream. This process provides essential energy for cells and metabolic functions.

Introduction

Carbohydrates are a vital class of nutrients, playing a central role in human metabolism and health. For nurses, understanding the biochemical processes of carbohydrate digestion and absorption is essential, not only for grasping normal physiology but also for managing patients with related disorders.

Importance of Carbohydrate Metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism is critical for energy production, cellular function, and overall well-being. Nurses frequently encounter patients with metabolic disorders, digestive issues, and dietary concerns related to carbohydrates. A solid grasp of the underlying biochemistry enables nurses to educate patients, monitor clinical symptoms, and contribute to multidisciplinary care plans. This document serves as a foundational resource for integrating biochemical knowledge into everyday nursing practice.

Types of Carbohydrates

Monosaccharides

Monosaccharides are the simplest form of carbohydrates, consisting of single sugar units. The most common monosaccharides include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Glucose is the primary energy source for the body, while fructose and galactose are metabolised in the liver. These sugars are found in fruits, honey, and some vegetables.

Disaccharides

Disaccharides are composed of two monosaccharide units linked by glycosidic bonds. The main dietary disaccharides are sucrose (glucose + fructose), lactose (glucose + galactose), and maltose (glucose + glucose). Sucrose is present in table sugar, lactose in milk, and maltose in malted foods.

Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides are complex carbohydrates made up of multiple monosaccharide units. Starch (found in cereals, potatoes, and legumes) and glycogen (the storage form in animals) are the principal polysaccharides. Dietary fibre, another polysaccharide, is indigestible but crucial for gut health.

Dietary Sources of Carbohydrates

- Fruits: Mangoes, bananas, apples, oranges

- Vegetables: Potatoes, sweet potatoes, corn

- Cereals and grains: Rice, wheat, maize, oats

- Pulses and legumes: Lentils, chickpeas, beans

- Dairy products: Milk (lactose)

- Sugar and sweets: Table sugar, jaggery, honey

Overview of Digestion

Definition and Purpose

Digestion is the process by which complex carbohydrates are broken down into absorbable monosaccharides. The primary purpose is to convert dietary carbohydrates into forms that can be readily utilised for energy production and metabolic processes.

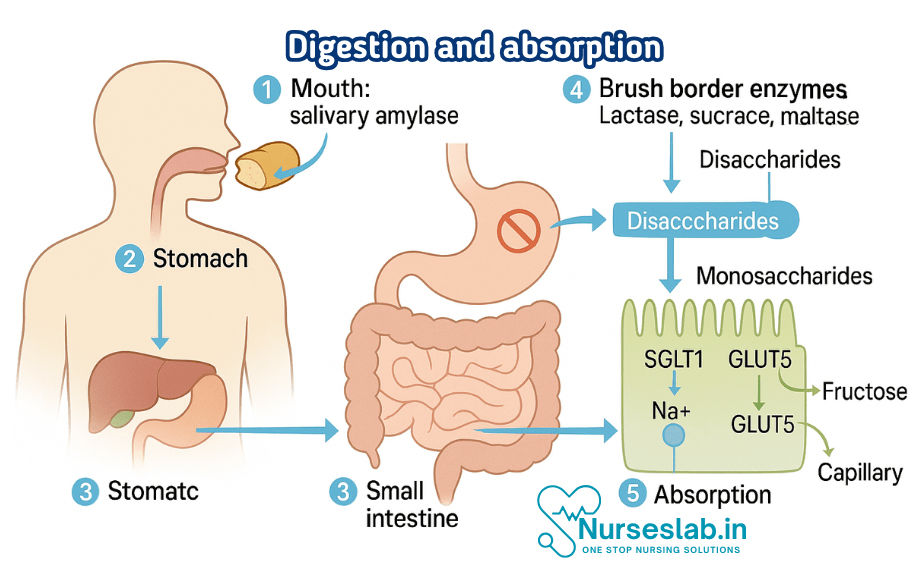

Stages of Carbohydrate Digestion

- Mouth: Initial breakdown by salivary enzymes

- Stomach: Limited digestion due to acidic environment

- Small intestine: Major breakdown by pancreatic and intestinal enzymes

- Absorption: Transport of monosaccharides across the intestinal wall

Digestion in the Mouth

Role of Salivary Amylase

Digestion of carbohydrates begins in the oral cavity, where salivary glands secrete the enzyme amylase. Salivary amylase hydrolyses starch into smaller polysaccharides and maltose. Chewing mechanically breaks down food, increasing the surface area for enzymatic action. This initial phase is brief, as food rapidly moves to the stomach.

Initial Breakdown

Salivary amylase acts optimally at neutral pH, initiating the conversion of starch to maltose and dextrins. However, not all carbohydrates are affected in the mouth; disaccharides and monosaccharides remain unchanged until later stages.

Digestion in the Stomach

Limited Carbohydrate Digestion

The acidic environment of the stomach (pH 1.5-3.5) inactivates salivary amylase, halting carbohydrate digestion temporarily. Mechanical mixing continues, but no further enzymatic breakdown of carbohydrates occurs in the stomach. Some dietary fibres and resistant starches begin to undergo fermentation by gastric microbes, but this is minimal compared to later stages.

Effects of Acidic Environment

The stomach’s acidity denatures most enzymes, including salivary amylase. Proteins and fats begin their digestion here, but carbohydrates remain largely unchanged. This pause ensures that significant carbohydrate digestion occurs in the small intestine, where conditions are optimal.

Digestion in the Small Intestine

Role of Pancreatic Amylase

Upon entering the duodenum, chyme (partially digested food) is exposed to pancreatic amylase, secreted by the pancreas. This enzyme continues the breakdown of starch into maltose, maltotriose, and dextrins. Pancreatic amylase is highly efficient due to the alkaline pH maintained by bicarbonate secretion.

Brush Border Enzymes

The final stage of carbohydrate digestion occurs at the brush border of the small intestinal epithelial cells. Here, enzymes such as maltase, sucrase, and lactase hydrolyse disaccharides into monosaccharides:

- Maltase: Converts maltose into two glucose molecules

- Sucrase: Splits sucrose into glucose and fructose

- Lactase: Breaks down lactose into glucose and galactose

These enzymes are embedded in the microvilli, ensuring efficient digestion at the absorption site.

Breakdown to Monosaccharides

By the end of small intestinal digestion, most carbohydrates are reduced to glucose, fructose, and galactose. These simple sugars are then ready for absorption into the bloodstream.

Absorption of Carbohydrates

Mechanisms of Absorption

Absorption of monosaccharides occurs primarily in the jejunum and ileum of the small intestine. Two main mechanisms are involved:

- Active Transport: Glucose and galactose are absorbed via sodium-dependent glucose transporter (SGLT1). This process requires energy (ATP) and relies on the sodium gradient maintained by the Na+/K+ ATPase pump.

- Facilitated Diffusion: Fructose is absorbed by GLUT5 transporter through facilitated diffusion, a passive process not requiring energy.

Absorption Sites and Pathways

Monosaccharides are transported across the apical membrane of enterocytes (intestinal cells) into the cytoplasm. From there, they exit via the basolateral membrane using GLUT2 transporter, entering the portal circulation en route to the liver.

Transport to the Liver

Once absorbed, glucose, galactose, and fructose are delivered to the liver via the hepatic portal vein. The liver plays a central role in carbohydrate metabolism, converting galactose and fructose into glucose, regulating blood sugar levels, and storing excess glucose as glycogen.

Fate of Absorbed Carbohydrates

Glycogenesis

Glycogenesis is the process of converting excess glucose into glycogen for storage, primarily in the liver and skeletal muscles. This stored glycogen serves as a readily available energy reserve for periods of fasting or increased activity.

Glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that breaks down glucose to produce ATP, the energy currency of cells. This process occurs in all tissues and is especially important in the brain and red blood cells, which rely exclusively on glucose for energy.

Energy Production

Complete oxidation of glucose through glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation yields approximately 36-38 ATP molecules per glucose molecule. This energy supports cellular functions, muscle activity, and maintenance of vital organs.

Clinical Relevance

Disorders of Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption

- Lactose Intolerance: Caused by lactase deficiency, leading to undigested lactose in the intestine. Symptoms include bloating, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain.

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions such as coeliac disease, tropical sprue, and chronic pancreatitis impair carbohydrate digestion and absorption. Clinical manifestations range from weight loss and nutrient deficiencies to chronic diarrhoea.

- Congenital Sucrase-Isomaltase Deficiency: A rare genetic disorder resulting in inability to digest sucrose and some starches, causing gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Glucose-Galactose Malabsorption: A genetic defect in SGLT1 transporter, leading to severe diarrhoea and dehydration in infants.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Common symptoms of carbohydrate malabsorption include abdominal discomfort, bloating, flatulence, diarrhoea, and weight loss. Diagnosis involves clinical history, dietary assessment, laboratory tests (hydrogen breath test for lactose intolerance), and stool analysis for reducing sugars.

Nursing Implications

Patient Education

Nurses play a crucial role in educating patients about carbohydrate digestion, dietary sources, and management of related disorders. Key points include:

- Explaining the importance of balanced carbohydrate intake

- Advising on suitable dietary choices for patients with intolerance or malabsorption

- Promoting awareness of symptoms and when to seek medical attention

- Encouraging adherence to prescribed dietary modifications

Dietary Management

For patients with lactose intolerance, nurses should recommend lactose-free dairy products, enzyme supplements, and alternative calcium sources. Those with malabsorption syndromes may require gluten-free diets, vitamin supplementation, and careful monitoring of nutritional status.

Monitoring and Assessment

Regular monitoring of symptoms, dietary intake, and weight is essential. Nurses should document changes, provide feedback to the healthcare team, and support patients through dietary transitions. In paediatric and geriatric populations, close observation is particularly important due to increased vulnerability.

REFERENCES

- Harbans Lal, Textbook of Applied Biochemistry and Nutrition& Dietetics 2nd Edition ,November 2024, CBS Publishers and Distributors, ISBN: 978-9394525757

- Suresh K Sharma, Textbook of Biochemistry and Biophysics for Nurses, 2nd Edition, September 2022, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-9354655760

- Peter J Kennelly, Harpers Illustrated Biochemistry Standard Edition, September 2022, McGraw Hill Lange Publishers, ISBN: 978-1264795673

- Denise R Ferrier, Ritu Singh, Lippincott Illustrated Reviews Biochemistry, Second Edition, June 2024, ISBN- 978-8197055973

- Yadav, Tapeshwar & Bhadeshwar, Sushma. (2022). Essential Textbook of Biochemistry for Nursing.

- Applied Sciences, Importance of Biochemistry for Nursing Practice, November 2, 2023, https://bns.institute/applied-sciences/importance-biochemistry-nursing-practice/

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.