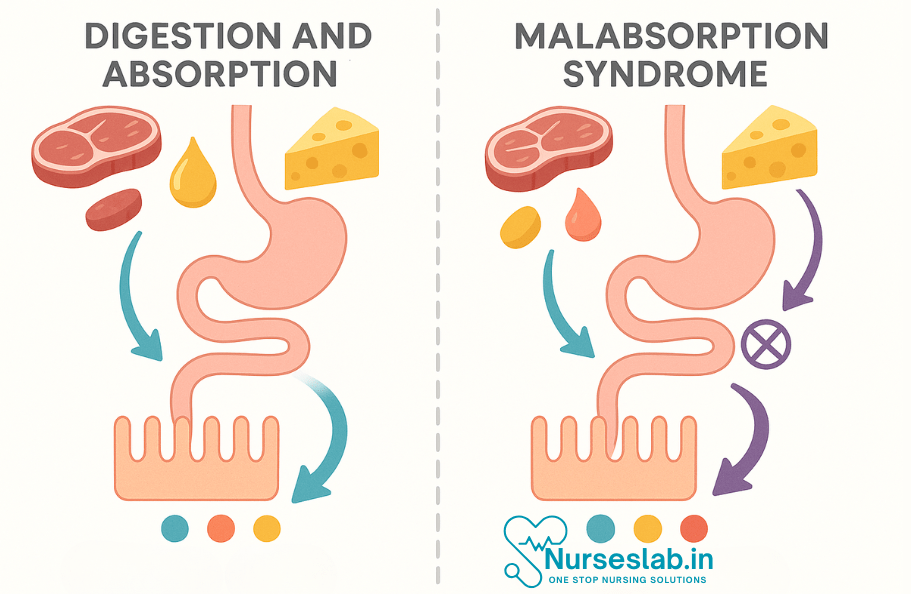

Digestion and absorption involve enzymatic breakdown and intestinal uptake of nutrients. Malabsorption syndromes result from conditions like celiac disease, pancreatic insufficiency, or infections, leading to poor nutrient absorption and clinical complications.

Introduction

The absorption process relies on several factors: the integrity of the intestinal mucosa, the presence of adequate digestive enzymes, and efficient nutrient transporters embedded in the epithelial cells. Any disruption in these processes can lead to malabsorption. For example, a deficiency in pancreatic enzymes impairs fat and protein digestion, while damage to the mucosal surface, as seen in coeliac disease, affects the absorption of all macronutrients and many micronutrients.

Overview of Digestion and Absorption

Digestion is the process by which complex food substances are broken down into simpler forms that can be absorbed and utilised by the body. Absorption is the subsequent movement of these nutrients from the gastrointestinal tract into the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Together, these processes ensure that the body receives the energy and building blocks necessary for cellular function, growth, and repair.

Disruptions in digestion or absorption can lead to malnutrition, illness, and impaired recovery, highlighting the importance of this topic in nursing care.

Factors Influencing Digestion

Enzyme Activity

The efficiency of digestive enzymes is influenced by several factors:

- Substrate Availability: Enzymes require specific substrates to function optimally.

- pH Levels: Each enzyme has an optimal pH (e.g., pepsin in the stomach at pH 1.5–2.0; pancreatic enzymes in the duodenum at pH 7–8).

- Temperature: Moderate body temperature favours enzyme activity; extremes can denature enzymes.

- Presence of Cofactors: Certain vitamins and minerals (e.g., zinc, magnesium) are essential for enzyme function.

Gastrointestinal Motility

Effective peristalsis and mixing movements are necessary for thorough digestion and timely transit of food along the GI tract. Delayed or rapid motility can impair digestion and absorption.

Dietary Factors

- Fibre Content: Insoluble fibre can speed up transit, while soluble fibre slows digestion and aids nutrient absorption.

- Fat Content: High-fat meals delay gastric emptying.

- Meal Size and Composition: Larger, complex meals take longer to digest.

- Presence of Anti-nutritional Factors: Compounds like phytates and tannins can inhibit digestive enzymes.

Age and Developmental Stage

Infants, children, adults, and the elderly have differing enzyme activity levels, gastric acidity, and gastrointestinal motility, all of which affect digestion efficiency.

Disease States

- Gastric Disorders: Conditions like gastritis, peptic ulcers, and atrophic gastritis can disrupt acid and enzyme production.

- Pancreatic Diseases: Chronic pancreatitis or cystic fibrosis can reduce enzyme output.

- Hepatobiliary Disorders: Impaired bile production affects fat digestion.

- Infections and Inflammation: Gastroenteritis, Crohn’s disease, and other inflammatory conditions interrupt normal digestion.

Factors Influencing Absorption

Surface Area of the Intestinal Mucosa

The small intestine’s villi and microvilli dramatically increase the absorptive surface area, facilitating efficient nutrient uptake. Conditions that damage this architecture (e.g., coeliac disease) significantly impair absorption.

Transport Mechanisms

- Passive Diffusion: Small, non-polar molecules move down their concentration gradient (e.g., water, some vitamins).

- Facilitated Diffusion: Utilises specific carrier proteins (e.g., fructose absorption via GLUT5).

- Active Transport: Requires ATP and carrier proteins (e.g., glucose and amino acid absorption).

- Endocytosis: Used for large molecules (e.g., immunoglobulins in infants).

Intestinal Health and Integrity

Healthy mucosa and tight junctions between epithelial cells are essential for selective absorption and preventing the entry of pathogens and toxins.

Nutrient Interactions

- Competition for Absorption: Excess of one nutrient can inhibit absorption of another (e.g., calcium and iron).

- Enhancers and Inhibitors: Vitamin C enhances iron absorption; phytates inhibit zinc absorption.

Physiological and Pathological Factors

- Hormonal Regulation: Hormones like secretin and cholecystokinin modulate digestive secretions and motility.

- Blood Flow: Adequate mesenteric circulation is vital for nutrient transport.

- Presence of Microbiota: Gut flora can aid in the synthesis and absorption of certain nutrients (e.g., vitamin K, biotin).

- Medications: Some drugs interfere with absorption (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics).

Factors Influencing Malabsorption

1. Enzymatic Deficiencies

Enzymatic deficiencies are a common cause of malabsorption. These can be congenital or acquired and often involve the pancreas or the brush border enzymes of the small intestine.

- Lactase Deficiency: Lactase, an enzyme located in the brush border of the small intestine, is responsible for breaking down lactose into glucose and galactose. Deficiency leads to lactose intolerance, causing bloating, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain after consuming dairy products.

- Pancreatic Insufficiency: The pancreas secretes enzymes like lipase, protease, and amylase essential for digesting fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. Conditions such as chronic pancreatitis or cystic fibrosis reduce enzyme production, resulting in steatorrhoea (fatty stools), weight loss, and deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).

- Sucrase-Isomaltase Deficiency: Less common but important, this brush border enzyme deficiency leads to an inability to digest certain sugars, resulting in diarrhoea and abdominal discomfort when sucrose or starch is ingested.

2. Structural Abnormalities

The structure and surface area of the small intestine are vital for effective absorption. Several conditions disrupt the mucosal integrity or reduce the available absorptive surface.

- Coeliac Disease: This autoimmune condition is triggered by gluten ingestion in genetically susceptible individuals. It leads to villous atrophy (flattening of the villi), reducing the absorptive surface and resulting in widespread malabsorption, particularly of iron, folate, calcium, and fat-soluble vitamins.

- Crohn’s Disease: A chronic inflammatory bowel disease that can cause patchy inflammation and ulceration throughout the GI tract. The resulting mucosal damage, strictures, and fistulae interfere with nutrient absorption and can cause protein-losing enteropathy.

- Surgical Resection (Short Bowel Syndrome): Removal of significant portions of the small intestine, often due to trauma or disease, leads to a dramatic reduction in absorptive area. This condition requires careful nutritional management and often lifelong supplementation.

3. Disease States Affecting Absorption

Several systemic and local diseases can impair nutrient absorption by altering the biochemical environment of the gut or by directly damaging the absorptive mechanisms.

- Infectious Diseases: Chronic infections like giardiasis or tropical sprue damage the mucosal lining, leading to malabsorption. Acute infections can also cause transient disruptions in absorption.

- Liver Disease: The liver produces bile acids necessary for fat emulsification and absorption. Conditions such as primary biliary cholangitis or cirrhosis reduce bile production or flow, resulting in fat malabsorption and deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins.

- Motility Disorders: Conditions like scleroderma or diabetic autonomic neuropathy lead to abnormal intestinal motility, causing bacterial overgrowth and subsequent nutrient malabsorption.

Nursing Considerations

- Ensure accurate documentation of dietary intake and symptoms.

- Assist with sample collection for investigations.

- Provide psychological support for patients coping with chronic illness and dietary restrictions.

- Advocate for patient needs within the multidisciplinary team.

- Monitoring and Assessment: Regularly monitor patient weight, growth (in children), hydration status, and laboratory parameters. Early identification of nutrient deficiencies allows for timely intervention.

- Patient Education: Educate patients and families about dietary modifications, importance of adherence to prescribed diets (e.g., gluten-free for coeliac disease), and recognition of symptoms indicating complications or deficiencies.

- Coordination with Multidisciplinary Teams: Work closely with dietitians, gastroenterologists, and pharmacists to ensure comprehensive care plans are developed and followed.

- Advocacy and Support: Advocate for necessary investigations, referrals, and resources. Provide psychological support to help patients cope with chronic illness and dietary restrictions.

- Sample Collection and Documentation: Ensure accurate and timely collection of specimens for laboratory analysis and maintain thorough documentation of symptoms, intake, and interventions.

REFERENCES

- Harbans Lal, Textbook of Applied Biochemistry and Nutrition& Dietetics 2nd Edition ,November 2024, CBS Publishers and Distributors, ISBN: 978-9394525757

- Suresh K Sharma, Textbook of Biochemistry and Biophysics for Nurses, 2nd Edition, September 2022, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-9354655760

- Peter J Kennelly, Harpers Illustrated Biochemistry Standard Edition, September 2022, McGraw Hill Lange Publishers, ISBN: 978-1264795673

- Denise R Ferrier, Ritu Singh, Lippincott Illustrated Reviews Biochemistry, Second Edition, June 2024, ISBN- 978-8197055973

- Yadav, Tapeshwar & Bhadeshwar, Sushma. (2022). Essential Textbook of Biochemistry for Nursing.

- Applied Sciences, Importance of Biochemistry for Nursing Practice, November 2, 2023, https://bns.institute/applied-sciences/importance-biochemistry-nursing-practice/

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.