Cancer pain is one of the most prevalent and distressing symptoms experienced by individuals diagnosed with cancer. It affects not only the physical well-being of the patient but also their emotional, psychological, and social health. As a complex phenomenon, cancer pain requires a nuanced understanding of its causes, manifestations, and the array of strategies available for its management.

What is Cancer Pain?

Cancer pain refers to the discomfort or unpleasant sensations associated with cancer itself or as a consequence of its treatment. Unlike other chronic pain conditions, cancer pain is often multifactorial, arising from the tumor’s direct effects, metastasis, treatment-related side effects, or from unrelated causes coinciding with the illness.

Cancer pain can be acute or chronic, intermittent or persistent, mild or severe. Its intensity and character may change over the course of the disease, making its assessment and management a dynamic process.

Causes of Cancer Pain

Cancer pain can originate from several sources:

- Tumor Invasion: The most common cause, where the tumor presses against bones, nerves, or other organs, leading to localized or radiating pain.

- Treatment Side Effects: Chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery can all cause pain, either at the site of treatment or as a systemic effect (e.g., neuropathy from chemotherapy).

- Diagnostic Procedures: Certain tests and biopsies may temporarily produce pain or discomfort.

- Coexisting Conditions: Not all pain in cancer patients is directly related to cancer; arthritis, migraines, or other chronic pain conditions may contribute.

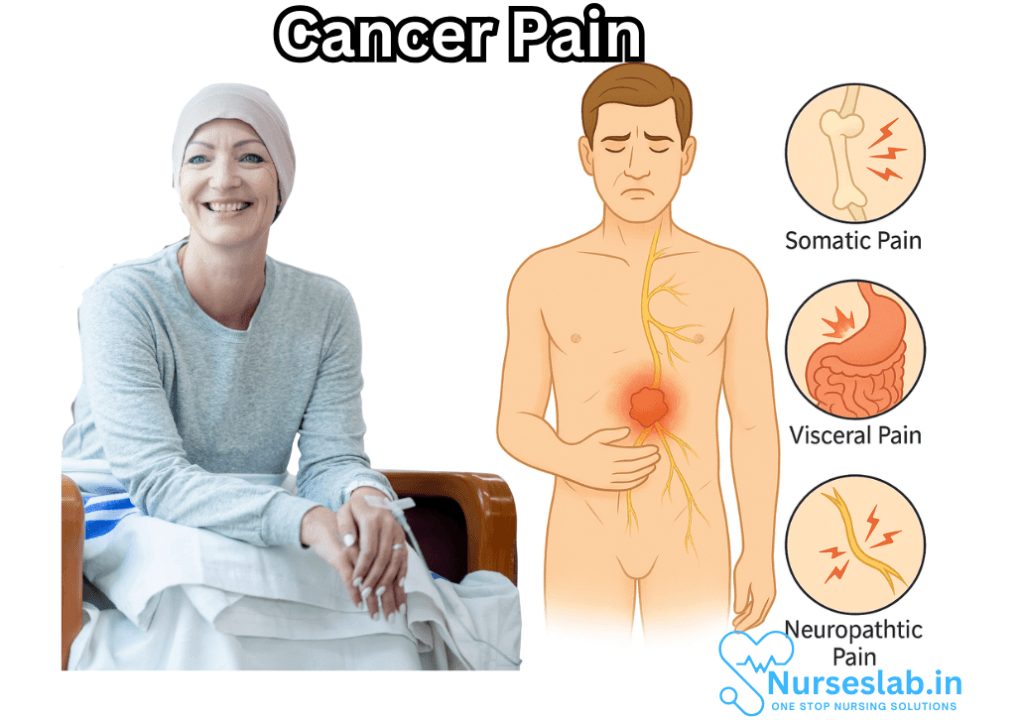

Types of Cancer Pain

It is important to recognize the different types of pain experienced by cancer patients, as this informs treatment strategies.

Nociceptive Pain

This form of pain arises from tissue injury. It is further classified into:

- Somatic Pain: Originates in skin, muscle, or bone. It is generally well localized and described as aching, throbbing, or sharp.

- Visceral Pain: Comes from internal organs. This pain is often diffuse, deep, and can be described as cramping or gnawing.

Neuropathic Pain

This pain results from injury or dysfunction of the nerves, either by tumor invasion or as a side effect of treatment like chemotherapy. Patients may describe it as shooting, burning, tingling, or electric shock-like sensations. Neuropathic pain can be particularly challenging to manage.

Breakthrough Pain

Despite regular pain control, some patients experience sudden, transient episodes of severe pain. These are known as breakthrough pain, often requiring fast-acting rescue medications.

Assessing Cancer Pain

Effective management of cancer pain begins with a thorough assessment. This involves:

- Detailed patient history regarding onset, location, intensity, character, and duration of pain.

- Understanding the impact of pain on daily activities, sleep, and mood.

- Physical examination and, if indicated, imaging or diagnostic studies to determine the underlying cause.

- Use of pain scales or questionnaires to quantify pain and assess response to treatment.

Open and empathetic communication between patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals is crucial to paint a complete picture and tailor the management plan.

Management Strategies

Cancer pain management is individualized, often requiring a multi-modal approach combining pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions.

Pharmacologic Treatments

- Non-Opioid Analgesics: Such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), useful for mild to moderate pain, especially bone pain.

- Opioids: Morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl, and others form the cornerstone for moderate to severe cancer pain. Their dosing must be individualized, balancing effective relief with side effect management.

- Adjuvant Medications: These include antidepressants, anticonvulsants (for neuropathic pain), corticosteroids, and bisphosphonates (for bone pain). They’re often used in combination with other pain relievers.

- Topical Agents: Creams or patches containing local anesthetics or capsaicin may provide localized relief.

The choice of medication, route of administration, and dosing schedule is carefully tailored to each patient’s needs, taking into account factors such as pain type, previous response to analgesics, and overall health.

Non-Pharmacologic Treatments

- Physical Therapy: Movement, massage, and appropriate exercise help maintain mobility and reduce discomfort.

- Pain-relieving Procedures: Nerve blocks, epidural infusions, or surgical interventions might be considered for intractable pain.

- Psychological Support: Counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and relaxation techniques can help patients cope with the emotional impact of chronic pain.

- Complementary Therapies: Acupuncture, meditation, art therapy, and music therapy may provide additional comfort and improve overall quality of life.

Barriers to Effective Pain Management

Despite advances, many patients still experience unrelieved cancer pain. Common barriers include:

- Patient-related: Fear of addiction, reluctance to report pain, misunderstanding about pain medications.

- Healthcare system-related: Limited access to pain specialists or medications, inadequate pain assessment by providers.

- Societal and Regulatory: Stigma associated with opioid use, restrictions on prescribing controlled substances.

Educating patients and families about the nature of cancer pain and the importance of timely intervention is vital to breaking these barriers.

The Psychological and Social Impact of Cancer Pain

Pain is not just a physical sensation. Cancer pain can lead to significant psychological distress, including anxiety, depression, and feelings of helplessness. It can impact relationships, social interactions, and a person’s sense of self-worth. Addressing these aspects is as important as treating the pain itself.

Palliative Care and Cancer Pain

Palliative care is a specialized field focused on improving quality of life for patients with serious illnesses. It emphasizes symptom management, including pain control, and involves a multidisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, social workers, psychologists, and spiritual counselors. Early integration of palliative care can significantly relieve suffering and help patients and families navigate the cancer journey.

The Role of Caregivers

Caregivers play a crucial role in recognizing and managing cancer pain. Their observations and advocacy are invaluable, as patients may underreport pain due to various fears or misconceptions. Support for caregivers, both educational and emotional, is essential for the well-being of the entire support network.

The Future of Cancer Pain Management

Research continues to advance the understanding and treatment of cancer pain. Innovations include:

- New medications and drug delivery systems designed to maximize relief and minimize side effects.

- Personalized medicine approaches, such as genomics, to predict pain response and tailor therapies.

- Neurostimulation techniques and new interventional procedures for refractory pain.

- Greater emphasis on holistic care, integrating physical, emotional, and spiritual support.

Nursing Care of Patients with Cancer Pain

The role of nurses in managing cancer pain is pivotal, as they are often at the forefront of care, providing both direct interventions and essential support for patients and their families. Understanding the nature of cancer pain and implementing a holistic, patient-centered approach is crucial for improving the quality of life for those affected.

Assessment of Cancer Pain

Accurate pain assessment is the cornerstone of effective pain management. The nurse must employ a systematic approach, using validated pain assessment tools and considering the following dimensions:

- Pain intensity: Measured using scales such as the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), or the Wong-Baker FACES scale.

- Location: Identifying all areas of pain.

- Quality: Descriptive terms—sharp, dull, aching, burning, stabbing, etc.

- Onset, duration, and pattern: When pain started, how long it lasts, and whether it is constant or intermittent.

- Aggravating and relieving factors: What worsens or improves the pain.

- Impact on function: Effects on sleep, appetite, mobility, mood, and daily activities.

- Response to current interventions: Medication effectiveness and side effects.

Regular reassessment is essential, as pain characteristics can change with disease progression or treatment.

Nursing Interventions for Cancer Pain

1. Pharmacological Management

The World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder is a widely accepted framework for managing cancer pain:

- Step 1: Non-opioid analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen, NSAIDs) for mild pain.

- Step 2: Weak opioids (e.g., codeine, tramadol) for moderate pain, possibly in combination with non-opioids.

- Step 3: Strong opioids (e.g., morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl) for severe pain, with or without non-opioids.

Adjuvant medications, such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, or bisphosphonates, may be used for neuropathic pain or bone pain. The nurse’s role includes:

- Administering prescribed analgesics safely and timely.

- Monitoring for and managing side effects (constipation, nausea, sedation, respiratory depression, etc.).

- Educating patients and families about medication use, potential side effects, and the importance of adherence.

- Advocating for adjustments to pain management plans as needed.

2. Non-Pharmacological Management

Complementing pharmacological treatment with non-drug interventions can improve pain control and support overall well-being:

- Physical interventions: Heat/cold applications, positioning, massage, physical therapy, and exercise (as tolerated).

- Cognitive-behavioral therapies: Relaxation techniques, guided imagery, distraction, mindfulness, and meditation.

- Complementary therapies: Acupuncture, aromatherapy, and music therapy.

- Patient education: Providing information on pain management strategies, dispelling myths about opioid use, and addressing fears of addiction.

3. Emotional and Psychosocial Support

Cancer pain is not only physical; it is deeply connected with emotional distress, anxiety, depression, and social isolation. Nurses provide support by:

- Creating a trusting relationship, listening empathetically to patients’ concerns and fears.

- Encouraging expression of feelings and facilitating communication within the family unit.

- Connecting patients and families with counseling, support groups, and spiritual care as needed.

- Monitoring for signs of psychological distress and referring to mental health professionals if appropriate.

4. Advocacy and Coordination of Care

Nurses often act as patient advocates, ensuring that pain management remains a priority in the care plan. This may involve:

- Communicating regularly with physicians and other healthcare providers to adjust pain regimens based on patient feedback.

- Ensuring continuity of pain management across settings (hospital, home, hospice).

- Coordinating multidisciplinary care, including palliative care specialists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, and social workers.

Special Considerations in Cancer Pain Management

Cultural and Individual Differences

Pain perception and expression can differ widely based on cultural, spiritual, and personal factors. Nurses must provide culturally competent care, respecting each patient’s beliefs and preferences and involving them in decision-making.

Management of Side Effects

Opioid therapy, while effective, is associated with side effects. Nurses monitor and manage issues like constipation (proactively using laxatives), vomiting, pruritus, and sedation. Patient education on these side effects and their management is critical.

Addressing Barriers to Pain Management

Barriers such as fear of addiction, concerns about tolerance, reluctance to report pain, or under-treatment by clinicians can impede effective pain management. Nurses play an important role in identifying and addressing these barriers through education, communication, and advocacy.

Palliative and End-of-Life Care

For patients with advanced disease, pain relief is a central goal of palliative and end-of-life care. The nurse’s role includes:

- Ensuring comfort and dignity are maintained at all times.

- Supporting families as they cope with the patient’s decline and possible death.

- Facilitating advance care planning and honoring patient wishes regarding pain management and life-sustaining treatments.

Documentation and Evaluation

Thorough documentation of pain assessment, interventions, patient responses, and side effects is essential for evaluating effectiveness and guiding future care. Regular evaluation allows for timely modifications to the plan of care, ensuring that pain is consistently managed.

REFERENCES

- Cancer Research UK. Causes and Types of Cancer Pain. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping/physically/cancer-and-pain-control/causes-and-types. Updated 1/12/2024.

- Bettaswamy G, Ambesh P, Kumar R, et al. Multicompartmental primary spinal extramedullary tumors: Value of an interdisciplinary approach. Asian J Neurosurg. 2017;12(04):674-680. doi:10.4103/ajns.AJNS_54_13

- Coveler AL, Mizrahi J, Eastman B, et al. Precision Promise Consortium. Pancreas Cancer-Associated Pain Management . https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8176967/. Oncologist. 2021 Jun;26(6):e971-e982.

- Craig T, Napolitano A, Brown M. Cancer survivors and cancer pain (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39234155/). BJA Educ. 2024 Sep;24(9):309-317.

- Ehrlich O, Lackowski A, Glover TL, et al. Use of Goals in Cancer Pain Management: A Systematic Review. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38851545/. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024 Sep;68(3):e194-e205.

- Park SH, Won JK, Kim CH, et al. Pathological classification of the intramedullary spinal cord tumors according to 2021 World Health Organization classification of central nervous system tumors, a single-institute experience. Neurospine. 2022;19(3):780-791. doi:10.14245/ns.2244196.098

- Makhlouf SM, Pini S, Ahmed S, et al. Managing Pain in People with Cancer-a Systematic Review of the Attitudes and Knowledge of Professionals, Patients, Caregivers and Public. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31119708/. J Cancer Educ. 2020 Apr;35(2):214-240.

- National Health Institute (U.S). National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Cancer and Complementary Health Approaches: What You Need to Know,.https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/cancer-and-complementary-health-approaches-what-you-need-to-know. Updated 10/2021.

- Caraceni A, Shkodra M. Cancer Pain Assessment and Classification. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Apr 10;11(4):510. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040510. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6521068/

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Palliative Care. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/palliative-patient.pdf. Updated 1/1/2023.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.