Chorea is a neurological movement disorder marked by involuntary, rapid, unpredictable muscle movements. It may result from Huntington’s disease, metabolic issues, infections, or medication effects. Understanding its causes, symptoms, and evaluation is essential in neurology and clinical practice.

Introduction

Chorea is a neurological disorder characterised by involuntary, irregular, and unpredictable movements that can affect various parts of the body. The term “chorea” is derived from the Greek word “choreia,” meaning “dance,” reflecting the dance-like movements observed in affected individuals. This condition has been recognised since ancient times, with historical references found in the writings of Hippocrates and later descriptions by Thomas Sydenham in the 17th century. Chorea is not a single disease but a clinical syndrome that can result from a variety of underlying causes, both hereditary and acquired.

Etiology: Causes and Risk Factors

Chorea can result from a wide range of etiologies, broadly classified into hereditary and acquired causes. The most well-known hereditary cause is Huntington’s disease, while acquired causes include autoimmune, infectious, metabolic, and drug-induced factors. Understanding the underlying cause is crucial for effective management.

Hereditary Causes

- Huntington’s Disease: An autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by a CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion in the HTT gene on chromosome 4. Onset typically occurs in mid-adulthood.

- Benign Hereditary Chorea: A rare, non-progressive condition usually presenting in childhood, often due to mutations in the NKX2-1 gene.

- Other Genetic Syndromes: Wilson’s disease, neuroacanthocytosis, and mitochondrial disorders may also present with chorea as a prominent feature.

Acquired Causes

- Sydenham’s Chorea: Most commonly seen in children following infection with group A β-haemolytic Streptococcus (rheumatic fever). It is an autoimmune phenomenon.

- Drug-Induced Chorea: Certain medications, such as levodopa, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants, can induce choreiform movements.

- Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders: Hyperthyroidism, hypoglycaemia, and electrolyte imbalances may precipitate chorea.

- Vascular Causes: Strokes affecting the basal ganglia, particularly the subthalamic nucleus, can result in hemichorea or hemiballismus.

- Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disorders: Systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome can cause chorea, often termed “chorea gravidarum” when occurring during pregnancy.

- Infectious Causes: HIV, tuberculosis, and other central nervous system infections may rarely present with chorea.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for chorea depend on the underlying cause. Family history is significant in hereditary forms, while recent streptococcal infection, pregnancy, autoimmune disease, and exposure to certain medications are notable in acquired cases.

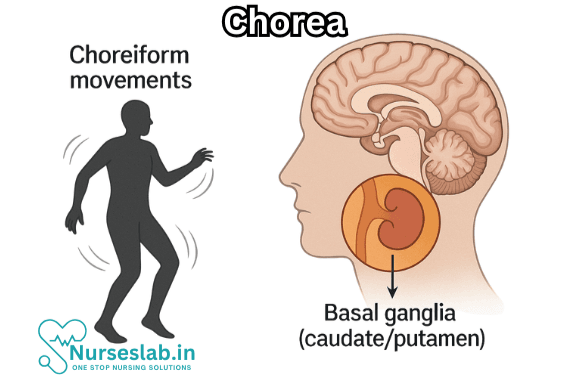

Pathophysiology: Mechanisms and Affected Systems

The hallmark of chorea is dysfunction of the basal ganglia, a group of subcortical nuclei involved in the regulation of voluntary motor control, procedural learning, and movement coordination. The most commonly affected structures are the caudate nucleus and putamen, collectively known as the striatum. Disruption of the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine, leads to the erratic firing of motor pathways and the characteristic involuntary movements.

In Huntington’s disease, progressive neuronal loss, particularly of medium spiny neurons in the striatum, results in reduced inhibitory output to the thalamus, causing excessive motor activity. In Sydenham’s chorea, immune-mediated cross-reactivity leads to inflammation and dysfunction of basal ganglia neurons. Drug-induced chorea generally results from alterations in dopaminergic transmission, either through receptor blockade or hypersensitivity.

Clinical Presentation: Signs and Symptoms

Chorea is clinically characterised by abrupt, random, and non-rhythmic movements that can affect the face, limbs, and trunk. The severity can range from mild fidgetiness to severe, disabling movements. Symptoms may fluctuate in intensity and are often aggravated by stress or voluntary actions.

Motor Symptoms

- Involuntary Movements: Sudden, unpredictable, and purposeless movements affecting various muscle groups.

- Facial Grimacing: Involuntary contractions of facial muscles, leading to abnormal expressions.

- Speech Disturbances: Dysarthria or slurred speech due to involvement of orofacial muscles.

- Gait Abnormalities: Unsteady, lurching gait often described as “dancing” or “prancing.”

- Motor Impersistence: Inability to sustain voluntary muscle contraction, e.g., difficulty keeping the tongue protruded.

Non-Motor Symptoms

- Cognitive Impairment: Common in Huntington’s disease, with progressive dementia, attention deficits, and impaired executive function.

- Psychiatric Manifestations: Depression, irritability, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behaviours, and psychosis.

- Sleep Disturbances: Insomnia and altered sleep patterns are frequently reported.

Diagnosis: Clinical Evaluation and Diagnostic Tests

Diagnosis of chorea involves a thorough clinical assessment, supported by laboratory and neuroimaging investigations to identify the underlying cause.

Clinical Assessment

- History: Detailed history of symptom onset, progression, family history, recent infections, medication use, and comorbid conditions.

- Physical Examination: Neurological examination focusing on involuntary movements, muscle tone, strength, coordination, and mental status.

Laboratory Investigations

- Genetic Testing: Confirmation of Huntington’s disease or other hereditary forms through analysis of specific gene mutations.

- Autoimmune Markers: Antistreptolysin O (ASO) titre, antinuclear antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies for Sydenham’s chorea and autoimmune causes.

- Metabolic Panel: Thyroid function tests, blood glucose, serum electrolytes, liver and renal function tests.

- Infectious Workup: Serological tests for HIV, tuberculosis, and other relevant pathogens in suspected infectious cases.

Neuroimaging

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): May reveal atrophy of the caudate nucleus and putamen in Huntington’s disease or acute lesions in vascular chorea.

- Computed Tomography (CT): Useful in acute settings to rule out haemorrhage or mass lesions.

- Functional Imaging: Positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may be used in research settings to assess striatal function.

Other Diagnostic Tools

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Typically normal but may help exclude epileptic phenomena.

- Neuropsychological Testing: Evaluation of cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, especially in hereditary choreas.

Types of Chorea

Chorea encompasses several distinct clinical syndromes, each with unique features and management considerations.

Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s disease (HD) is the prototypical hereditary chorea, presenting with a triad of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms. Progressive neurodegeneration leads to worsening disability and ultimately death, often within 15–20 years of symptom onset. The diagnosis is confirmed by genetic testing for expanded CAG repeats in the HTT gene.

Sydenham’s Chorea

Sydenham’s chorea (SC) predominantly affects children and adolescents, typically occurring weeks to months after a streptococcal throat infection. It is a major manifestation of acute rheumatic fever and is characterised by rapid, involuntary movements, hypotonia, and emotional lability. The course is usually self-limiting, with most cases resolving within 3–6 months.

Other Types

- Chorea Gravidarum: Chorea occurring during pregnancy, often associated with underlying rheumatic heart disease or antiphospholipid syndrome.

- Drug-Induced Chorea: Reversible chorea due to medications affecting dopaminergic or serotonergic pathways.

- Vascular Chorea: Sudden onset following stroke, typically unilateral (hemichorea).

- Metabolic and Toxic Chorea: Resulting from systemic metabolic disturbances or exposure to toxins.

Treatment: Medical and Supportive Therapies

The management of chorea is tailored to the underlying cause and the severity of symptoms. Treatment strategies include addressing the aetiology, symptomatic control, and supportive care.

Addressing the Underlying Cause

- Huntington’s Disease: No disease-modifying therapy is currently available. Management is symptomatic, focusing on motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms.

- Sydenham’s Chorea: Antibiotic therapy (e.g., penicillin) to eradicate streptococcal infection and prevent recurrence. Immunomodulatory treatments such as corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), or plasmapheresis may be considered in severe cases.

- Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders: Correction of underlying metabolic or hormonal disturbances.

- Drug-Induced Chorea: Discontinuation or substitution of the offending agent.

- Autoimmune Chorea: Immunosuppressive therapies for conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Symptomatic Treatment

- Antidopaminergic Agents: Typical and atypical antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol, risperidone, olanzapine) are commonly used to suppress choreiform movements by blocking dopamine receptors.

- VMAT2 Inhibitors: Tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine reduce presynaptic dopamine release and are approved for the treatment of chorea in Huntington’s disease.

- Benzodiazepines: Clonazepam and diazepam may provide additional benefit, particularly in cases with anxiety or agitation.

- Anticonvulsants: Valproate and carbamazepine have been used in certain cases, especially when chorea is associated with seizures.

Supportive Therapies

- Physiotherapy: Helps maintain mobility, flexibility, and balance.

- Occupational Therapy: Assists patients in adapting to daily living activities and maximising independence.

- Speech and Language Therapy: Improves communication and swallowing difficulties.

- Psychological Support: Counselling and psychiatric care for mood and behavioural disturbances.

- Social Support: Involvement of family, caregivers, and community resources to provide comprehensive care.

Prognosis: Outcomes and Complications

The prognosis of chorea varies significantly depending on the underlying cause. In Sydenham’s chorea, the outlook is generally favourable, with most patients making a full recovery. However, relapses can occur, and a minority may experience persistent symptoms. In contrast, Huntington’s disease carries a poor prognosis, with relentless progression of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric decline leading to profound disability and premature death.

Complications of chorea include injuries related to falls, aspiration pneumonia due to swallowing difficulties, malnutrition, and severe psychological distress. In children, academic performance and social development may be adversely affected. Early recognition and intervention are critical in minimising complications and optimising quality of life.

Impact on Patients:

Chorea has a profound impact on the lives of affected individuals and their families. The unpredictable and often stigmatising nature of involuntary movements can lead to social isolation, embarrassment, and loss of self-esteem. Children with chorea may face bullying and difficulties in school, while adults may struggle with employment and interpersonal relationships.

Psychiatric symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and irritability, are common and may precede or exacerbate motor manifestations. Cognitive decline, particularly in Huntington’s disease, further impairs functional independence and decision-making capacity. Caregiver burden is significant, often leading to emotional, financial, and physical strain.

Multidisciplinary care, including medical, psychological, and social support, is essential in addressing the complex needs of patients and improving overall wellbeing.

Nursing Care of a Patient with Chorea

Effective nursing care requires a comprehensive, patient-centered approach, focusing not only on the physical manifestations but also on the psychological, social, and safety concerns associated with the disorder.

Nursing Assessment

Accurate and holistic assessment forms the backbone of nursing care. Key elements include:

- History Taking: Ascertain onset, duration, frequency, and pattern of movements. Note any associated symptoms such as cognitive changes, behavioral alterations, or functional decline.

- Physical Examination: Observe the type, distribution, and impact of involuntary movements. Assess for injuries or complications resulting from movements, such as bruises, falls, or skin breakdown.

- Mental and Emotional Status: Evaluate mood, cognition, and risk of depression or anxiety, as these are common in chronic neurological disorders.

- Medication Review: Document all current medications and recent changes, as some drugs may exacerbate or trigger chorea.

- Functional Assessment: Assess ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), including feeding, dressing, mobility, and communication.

Goals of Nursing Care

- Maintain patient safety and prevent injury.

- Promote optimal physical functioning and independence.

- Support emotional and psychological well-being.

- Enhance quality of life for both patient and family.

- Educate patient and caregivers about condition management and coping strategies.

Key Nursing Interventions

1. Safety Promotion

- Environment Modification: Remove hazards, sharp objects, and clutter from the patient’s room. Use bed rails if necessary, but avoid physical restraints unless absolutely essential and prescribed.

- Fall Prevention: Place non-slip mats; ensure patient wears appropriate, stable footwear; assist with transfers and ambulation.

- Monitoring: Closely observe for risk of injury during periods of intense movements. Educate caregivers on safe transfer techniques.

- Skin Integrity: Inspect skin daily for breakdown or injuries. Use protective padding as needed to prevent pressure injuries or trauma from movements.

2. Assistance with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

- Feeding: Provide a calm environment during meals. If swallowing is impaired, consult with a speech-language pathologist for appropriate dietary modifications (e.g., thickened liquids, soft diet). Encourage small, frequent meals to reduce fatigue.

- Personal Hygiene: Assist with bathing, grooming, and dressing as needed, allowing the patient as much independence as possible. Use adaptive devices if appropriate.

- Mobility: Provide walking aids and ensure assistance during ambulation. Encourage regular, gentle exercises to maintain muscle strength and joint flexibility under supervision.

3. Medication Management

- Administration: Administer antichoreic medications as prescribed (e.g., tetrabenazine, antipsychotics). Be alert for side effects such as sedation, depression, or parkinsonism.

- Monitoring: Regularly evaluate effectiveness and tolerance of medications. Communicate with the healthcare team about any changes in symptoms or adverse effects.

- Education: Teach patient and caregivers about medication purpose, timing, potential side effects, and the importance of adherence.

4. Emotional and Psychological Support

- Counseling: Provide a supportive environment for expressing fears, frustrations, and anxieties. Refer to mental health professionals as needed.

- Support Groups: Encourage participation in support groups for patients with movement disorders. Connecting with others facing similar challenges can foster resilience and hope.

- Family Involvement: Involve family members in care planning, providing education and emotional support to reduce caregiver burden and improve coping.

5. Communication Enhancement

- Speech Therapy: Refer to a speech-language pathologist if communication is impaired. Use alternative communication methods, such as picture boards or electronic devices, as needed.

- Patience and Understanding: Allow extra time for the patient to respond to questions or express needs. Avoid rushing or interrupting.

6. Nutritional Support

- Dietary Assessment: Ensure adequate caloric and fluid intake, as choreic movements can increase energy expenditure.

- Swallowing Evaluation: Monitor for signs of dysphagia (coughing, choking, wet voice). Implement dietary modifications as recommended by specialists.

- Feeding Assistance: Offer assistance during meals, and use adaptive utensils to foster independence.

7. Education for Patient and Caregivers

- Condition Understanding: Explain the nature of chorea, possible causes, treatment options, and prognosis in simple, understandable language.

- Symptom Management: Teach strategies to manage triggers or exacerbating factors. Stress reduction techniques, such as deep breathing or music therapy, may be helpful.

- Emergency Preparedness: Train caregivers on what to do in case of falls, choking, or sudden changes in consciousness.

Special Considerations

- Pediatric Patients: Children with chorea (e.g., Sydenham’s chorea) require age-appropriate education, emotional reassurance, and support with school activities.

- Older Adults: Be vigilant for comorbidities, polypharmacy, and increased susceptibility to falls or confusion.

- Chronic Progressive Disease: In diseases like Huntington’s, anticipate progressive decline. Advanced care planning and discussions about goals of care should be initiated early.

Collaboration with Multidisciplinary Team

Nurses play a pivotal role in coordinating with physicians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, dietitians, and social workers. Regular case discussions ensure a tailored care plan that meets the evolving needs of the patient.

Documentation and Evaluation

- Document all assessments, interventions, and patient responses promptly and accurately.

- Regularly review and update the care plan based on the patient’s progress and changing needs.

- Involve the patient and family in care evaluations to promote shared decision-making and satisfaction.

REFERENCES

- Bashir H, Jankovic J. Treatment Options for Chorea, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29120264. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018 Jan;18(1):51-63.

- Lui F, Merical B, Sánchez-Manso JC. Chorea. [Updated 2025 Jan 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK430923/

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (U.S.). Sydenham’s Chorea. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7716/sydenhams-chorea). Last reviewed 2/2023.

- The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS). Chorea & Huntington’s Disease. https://www.movementdisorders.org/MDS/About/Movement-Disorder-Overviews/Chorea–Huntingtons-Disease.htm. Last reviewed 2019.

- Merck Manual. Chorea, Athetosis and Hemiballismus. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/brain,-spinal-cord,-and-nerve-disorders/movement-disorders/chorea-athetosis-and-hemiballismus. Last reviewed 9/2022. .

- Merical B, Sánchez-Manso JC. Chorea. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430923/. [Updated 2022 Jul 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- Feinstein E, Walker R. Treatment of secondary chorea: A review of the current literature. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2020;10:22. doi:10.5334/tohm.351

- Termsarasab P. Chorea. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31356291/. American Academy of Neurology. Continuum. 2019 Aug; 25(4):1001-1035.

- Martinez-Ramirez D, Walker RH, Rodríguez-Violante M, Gatto EM. Rare movement disorders study group of international Parkinson’s disease. Review of hereditary and acquired rare choreas. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2020;10:24. doi:10.5334/tohm.548

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.