Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is a serious condition caused by persistent pulmonary emboli leading to elevated pulmonary pressures. Understanding its symptoms, diagnosis, imaging, and treatment options is essential in cardiology, pulmonology, and clinical practice.

Introduction

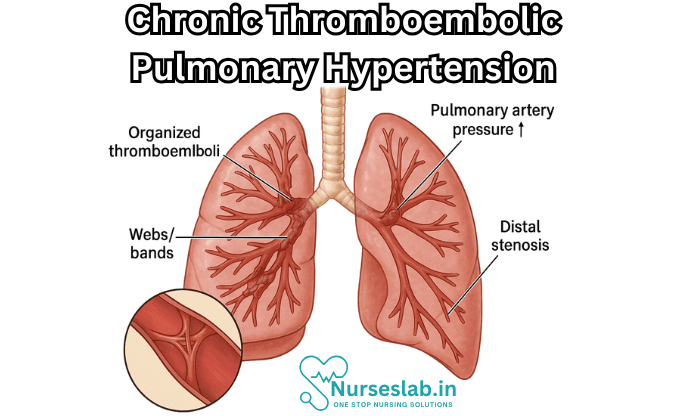

Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH) is an uncommon yet potentially curable form of pulmonary hypertension (PH) that arises as a consequence of unresolved thromboembolic occlusion of the pulmonary vasculature. Characterised by persistent obstruction of pulmonary arteries by organised thromboemboli and subsequent vascular remodelling, CTEPH leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and progressive right heart failure.

The disease is classified under Group 4 of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of pulmonary hypertension. The clinical significance of CTEPH lies in its unique pathophysiological mechanisms, diagnostic challenges, and the availability of potentially curative surgical interventions.

Definition and Classification

CTEPH is defined as a form of pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary arterial pressure >20 mmHg at rest, with pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤15 mmHg) that persists for more than three months after adequate anticoagulation, in the presence of chronic thromboembolic material within the pulmonary arteries.

It is categorised under WHO Group 4 pulmonary hypertension, distinct from other forms such as idiopathic, heritable, or associated with left heart disease and lung disorders. The hallmark of CTEPH is the presence of non-resolving, organised thrombi in the pulmonary arteries, leading to both mechanical obstruction and secondary small-vessel arteriopathy.

Epidemiology: Prevalence, Incidence, and Risk Factors

CTEPH is considered a rare complication of acute pulmonary embolism (PE). The estimated incidence is between 0.5% and 5% among survivors of acute PE, although the true incidence may be underreported due to diagnostic challenges and under-recognition. The prevalence of CTEPH is estimated at approximately 3–30 cases per million population. The disease affects adults of all ages, with a slight female preponderance noted in some studies.

Several risk factors have been identified for the development of CTEPH, including:

- History of acute pulmonary embolism: The single most important risk factor, although up to 25–50% of patients with CTEPH do not recall a prior episode of symptomatic PE.

- Splenectomy: Patients who have undergone splenectomy have an increased risk, possibly due to altered coagulation and platelet function.

- Chronic inflammatory diseases: Conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and osteomyelitis are associated with a higher risk.

- Ventriculo-atrial shunts: These shunts, used for hydrocephalus management, have been implicated in CTEPH development.

- Malignancy, thyroid replacement therapy, and antiphospholipid syndrome: These conditions are also recognised as risk factors.

- Genetic predisposition: Although not as well defined as in other forms of pulmonary hypertension, genetic factors may play a role.

It is important to note that traditional risk factors for venous thromboembolism, such as immobility and surgery, may not always predict CTEPH development.

Pathophysiology

CTEPH arises from incomplete resolution of thromboembolic material in the pulmonary arteries following an episode of acute PE. Normally, thrombi are lysed or organised and incorporated into the vessel wall. However, in CTEPH, the process of thrombus resolution is defective, resulting in fibrotic, organised material that adheres to the vessel wall and causes persistent obstruction.

The pathophysiological mechanisms involved include:

- Mechanical Obstruction: Organised thrombi cause fixed, non-reversible narrowing or occlusion of the central and proximal pulmonary arteries.

- Small-vessel Arteriopathy: Distal to the obstructed vessels, remodelling occurs in the small pulmonary arteries and arterioles, similar to changes seen in other forms of pulmonary hypertension. This is believed to be driven by increased shear stress, hypoxia, and secondary endothelial dysfunction.

- Vascular Remodelling: The remodelling includes intimal fibrosis, medial hypertrophy, and in situ thrombosis, further increasing pulmonary vascular resistance.

- Right Ventricular Dysfunction: Chronic pressure overload leads to right ventricular hypertrophy, dilation, and eventually right heart failure.

The combination of mechanical obstruction and secondary arteriopathy explains why some patients with limited thrombotic burden develop severe pulmonary hypertension, while others with extensive obstruction may have relatively mild symptoms.

Clinical Presentation

CTEPH typically presents insidiously, with non-specific symptoms that may be mistaken for other cardiopulmonary conditions. The clinical features include:

- Dyspnoea on exertion: The most common presenting symptom, often progressing slowly over months to years.

- Fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance: Reflective of impaired cardiac output.

- Chest pain: Usually atypical, sometimes reflecting right ventricular strain or ischaemia.

- Syncope or near-syncope: Occurs in advanced disease due to reduced cardiac output.

- Haemoptysis: May be seen in a minority, resulting from rupture of bronchial arteries or in situ thrombosis.

On physical examination, findings may include:

- Loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound (P2).

- Right ventricular heave.

- Jugular venous distension.

- Peripheral oedema, hepatomegaly, and ascites: Signs of right heart failure in advanced stages.

The progression of CTEPH is variable. Some patients remain stable for years, while others experience rapid deterioration. Early diagnosis is crucial, as timely intervention can be curative in many cases.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CTEPH requires a high index of suspicion, especially in patients with unexplained dyspnoea and a history of pulmonary embolism. The diagnostic approach involves confirming the presence of pulmonary hypertension, identifying chronic thromboembolic obstruction, and excluding other causes.

Diagnostic Criteria

The current diagnostic criteria for CTEPH include:

- Mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) >20 mmHg at rest, measured by right heart catheterisation.

- Pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤15 mmHg.

- Persistent perfusion defects on imaging after at least three months of effective anticoagulation.

- Exclusion of other causes of pulmonary hypertension.

Imaging Modalities

Imaging plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis and assessment of CTEPH:

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Scan: A sensitive screening test; mismatched segmental perfusion defects are highly suggestive of CTEPH.

- Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA): Provides detailed anatomical information and can identify chronic thromboembolic material, webs, bands, and stenoses.

- Pulmonary Angiography: The gold standard for visualising pulmonary artery obstructions; now often performed as digital subtraction angiography.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Useful for assessing right ventricular function and pulmonary artery flow.

- Echocardiography: Non-invasive assessment of pulmonary pressures and right ventricular size and function; useful for screening but not definitive.

Laboratory and Functional Testing

Laboratory tests are primarily used to exclude other causes of pulmonary hypertension and to assess comorbid conditions:

- Blood tests: Full blood count, renal and liver function tests, thyroid function, and autoimmune screening.

- Cardiac biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) may be elevated, reflecting right ventricular strain.

- Six-minute walk test (6MWT): Assesses functional capacity and response to therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of pulmonary hypertension, such as idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), left heart disease, chronic lung disease, and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Distinguishing CTEPH from these conditions is critical, as management strategies differ significantly.

Management

Management of CTEPH is multidisciplinary, involving pulmonologists, cardiologists, radiologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons. The primary goal is to reduce pulmonary vascular resistance, improve symptoms, and enhance survival.

1.Medical Therapy

All patients with CTEPH should receive lifelong anticoagulation to prevent further thromboembolic events. Vitamin K antagonists (e.g., warfarin) have been traditionally used, but direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are increasingly considered, though data are limited.

In patients who are not surgical candidates or have persistent pulmonary hypertension after surgery, targeted pulmonary hypertension therapies may be employed:

- Riociguat: A soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator, is the only approved medical therapy for inoperable or persistent/recurrent CTEPH. It improves exercise capacity and haemodynamics.

- Endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, and prostacyclin analogues: Their use is off-label and generally reserved for selected patients.

2.Surgical Interventions

Pulmonary Endarterectomy (PEA) is the treatment of choice for eligible patients with operable CTEPH. It involves surgical removal of organised thromboembolic material from the pulmonary arteries. PEA is a complex procedure, requiring expertise in specialised centres, but it offers the potential for cure and significant improvement in survival and quality of life.

Patient selection for PEA depends on the distribution of thromboembolic disease, comorbidities, and surgical risk. Proximal disease is more amenable to surgery, whereas distal disease may not be accessible.

3.Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty (BPA)

For patients with inoperable or distal CTEPH, Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty (BPA) has emerged as a promising intervention. BPA involves percutaneous dilation of stenotic or occluded pulmonary arteries using balloon catheters. Multiple sessions may be required, and the procedure is associated with significant improvements in haemodynamics, exercise capacity, and symptoms. Complications include reperfusion pulmonary oedema and vascular injury, but these are decreasing with improved technique.

4.Supportive Care

Supportive measures are crucial in the management of CTEPH:

- Oxygen therapy: For patients with hypoxaemia.

- Diuretics: To manage right heart failure and fluid overload.

- Rehabilitation: Exercise training and pulmonary rehabilitation improve functional status.

- Psychosocial support: Addressing the emotional and psychological impact of chronic illness.

Prognosis

The prognosis of CTEPH has improved significantly with advances in diagnosis and treatment. Without intervention, CTEPH carries a poor prognosis, with a three-year survival rate of approximately 30% in patients with severe haemodynamic impairment.

Pulmonary endarterectomy dramatically improves survival, with five-year survival rates exceeding 85% in selected patients. Outcomes are influenced by the degree of right ventricular dysfunction, extent of disease, and presence of comorbidities.

Quality of life is markedly improved in patients undergoing successful intervention, with significant gains in exercise capacity, symptom burden, and psychosocial well-being. However, a subset of patients may have persistent or recurrent pulmonary hypertension post-PEA, requiring further medical or interventional therapy.

Prognostic factors include:

- Access to specialised centres: Experience of the surgical team and centre volume are crucial determinants of outcome.

- Preoperative haemodynamics: Higher pulmonary vascular resistance and right atrial pressure are associated with worse outcomes.

- Completeness of surgical endarterectomy: Incomplete removal of thromboembolic material predicts persistent PH.

- Comorbidities: Renal dysfunction, advanced age, and left heart disease negatively affect prognosis.

Nursing Care of Patients with Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH)

Nurses play a pivotal role in the multidisciplinary management of patients with CTEPH, providing holistic care that addresses not only the physical symptoms, but also the emotional and psychosocial needs of the patient and their family.

Assessment and Nursing Diagnosis

Comprehensive assessment is essential for tailoring effective nursing interventions. Key areas of focus include:

- Respiratory Assessment: Monitor for dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, cyanosis, and respiratory distress. Assess breath sounds, oxygen saturation, and respiratory rate regularly.

- Cardiovascular Assessment: Evaluate for signs of right ventricular failure, such as jugular venous distension, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and ascites. Monitor heart rate, rhythm, and blood pressure.

- Functional Status: Use standardized tools (e.g., 6-minute walk test) where appropriate to assess exercise tolerance and monitor for changes over time.

- Psychosocial Assessment: Gauge the patient’s coping mechanisms, psychological wellbeing, knowledge of the disease, and support systems.

- Medication Review: Assess for proper adherence to anticoagulants, vasodilators, or other prescribed medications.

Nursing diagnoses may include:

- Ineffective breathing pattern related to increased pulmonary vascular resistance.

- Decreased cardiac output related to right ventricular dysfunction.

- Impaired physical mobility related to fatigue and dyspnea.

- Anxiety related to chronic illness and uncertainty about prognosis.

- Deficient knowledge regarding disease management.

Nursing Interventions

1. Optimizing Oxygenation and Respiratory Function

- Administer supplemental oxygen as prescribed to maintain oxygen saturation above target range (typically >90%).

- Promote upright positioning to maximize lung expansion and reduce dyspnea.

- Teach breathing techniques (e.g., pursed-lip breathing) to alleviate symptoms of breathlessness.

- Monitor for signs of worsening hypoxemia, including confusion, restlessness, and cyanosis, and notify provider accordingly.

2. Managing Cardiovascular Complications

- Closely monitor vital signs and cardiac rhythm for evidence of arrhythmias or hypotension.

- Assess for and document any new or worsening peripheral edema, indicating right heart failure progression.

- Provide low-sodium diet education to minimize fluid retention.

- If prescribed, administer diuretics, carefully monitoring fluid balance and electrolytes.

- Encourage gradual, monitored physical activity as tolerated to prevent deconditioning and promote venous return.

3. Anticoagulant Therapy Management

- Educate the patient regarding the importance of strict adherence to anticoagulation therapy to prevent further thromboembolic events.

- Monitor for signs of bleeding (e.g., bruising, hematuria, gastrointestinal bleeding) and educate about precautions (e.g., avoiding contact sports, using soft toothbrushes).

- Arrange for regular monitoring of coagulation parameters such as INR or anti-Xa levels, depending on the prescribed anticoagulant.

- Coordinate with pharmacy and provider to manage potential drug interactions.

4. Preparing for and Supporting Surgical or Interventional Procedures

- For patients considered for pulmonary endarterectomy or balloon pulmonary angioplasty, provide thorough preoperative education about the procedure, risks, and postoperative expectations.

- Ensure preoperative optimization, including stable anticoagulation and comorbidity management.

- Offer emotional support and address fears regarding surgery or invasive interventions.

- Postoperatively, monitor for complications such as bleeding, infection, arrhythmias, and respiratory compromise.

- Facilitate early ambulation and respiratory exercises to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications.

5. Promoting Activity and Energy Conservation

- Collaborate with physical therapy for the development of individualized exercise plans.

- Teach the patient to pace activities, use rest periods, and recognize early signs of exertional intolerance.

- Encourage use of assistive devices if needed to maintain independence with daily tasks.

6. Providing Emotional and Psychosocial Support

- Listen actively to the patient’s concerns and provide reassurance.

- Facilitate access to counseling, support groups, or peer networks for patients and families coping with chronic illness.

- Educate about the chronic nature of CTEPH, potential lifestyle modifications, and realistic expectations for prognosis and quality of life.

7. Patient and Family Education

- Provide information on signs and symptoms that require immediate medical attention (e.g., sudden chest pain, severe shortness of breath, swelling of legs).

- Educate about the importance of lifelong follow-up and regular assessment with the multidisciplinary team.

- Discuss the need for immunizations (e.g., influenza, pneumococcal vaccines) to reduce infection risk.

- Clarify the rationale for each medication, possible side effects, and strategies to enhance adherence.

Interprofessional Collaboration

CTEPH management requires a team approach. Nurses coordinate care with pulmonologists, cardiologists, surgeons, pharmacists, physical therapists, dietitians, and social workers. Effective communication and timely handovers are crucial to prevent complications and ensure seamless transitions through various phases of care.

Monitoring and Outcome Evaluation

Regular follow-up and reassessment are essential. Nurses should document and monitor:

- Trends in functional status and exercise tolerance.

- Effectiveness and adverse effects of medications and interventions.

- Signs of disease progression or complications.

- Patient and caregiver understanding of management and follow-up requirements.

Periodic evaluation allows timely adjustment of the care plan to optimize outcomes.

End-of-Life Care Considerations

For patients with advanced CTEPH who are not surgical candidates and have refractory symptoms, palliative care principles become increasingly important. Nurses should:

- Advocate for symptom control (e.g., management of dyspnea, fatigue, pain).

- Facilitate discussions regarding goals of care, advanced directives, and preferences for life-sustaining treatments.

- Support families through anticipatory grief and bereavement processes.

REFERENCES

- American Thoracic Society. Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. https://www.thoracic.org/patients/patient-resources/resources/cteph.pdf.

- Estrada RA, Auger WR, Sahay S. Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. JAMA. 2024;331(11):972–973. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.24265

- CHEST® Foundation (American College of Chest Physicians). About Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH). https://foundation.chestnet.org/lung-health-a-z/chronic-thromboembolic-pulmonary-hypertension-cteph/.

- Kim NH, Delcroix M, Jais X, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6351341/. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801915. Published 2019 Jan 24.

- Sabbula BR, Sankari A, Akella J. Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. 2024 Mar 4. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 31751026.

- NORD® – National Organization for Rare Disorders. NIH GARD Information: Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension. https://rarediseases.org/gard-rare-disease/chronic-thromboembolic-pulmonary-hypertension/.

- Matusov Y, Singh I, Yu YR, Chun HJ, Maron BA, Tapson VF, Lewis MI, Rajagopal S. Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension: the Bedside. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021 Aug 19;23(10):147. doi: 10.1007/s11886-021-01573-5. PMID: 34410530; PMCID: PMC8375459.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.