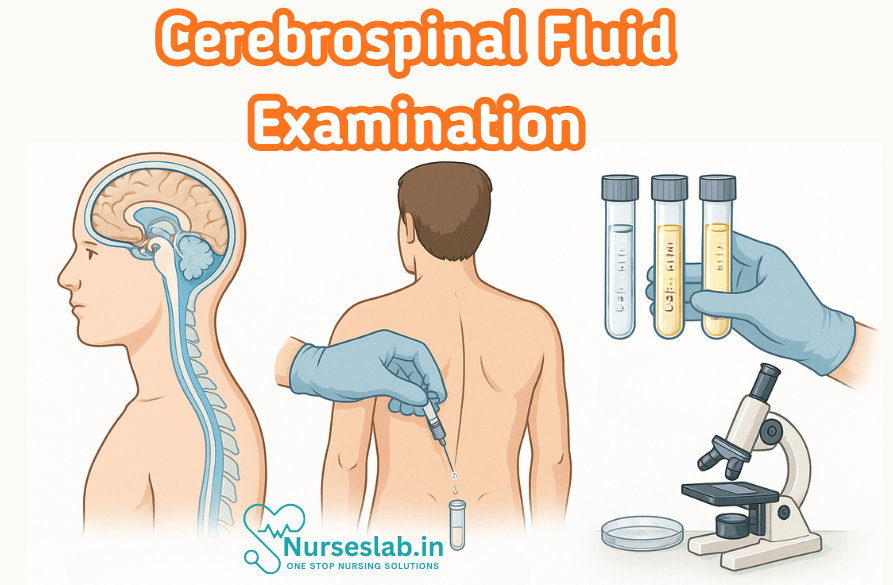

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination is a vital diagnostic test used to detect infections, bleeding, autoimmune diseases, and neurological disorders. It involves analyzing fluid collected via lumbar puncture to guide accurate diagnosis and patient care.

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination is a cornerstone diagnostic procedure in neurology and clinical pathology. CSF is a clear, colourless fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord, providing protection, nourishment, and waste removal for the central nervous system (CNS). The analysis of CSF offers vital clues in the diagnosis, monitoring, and management of a wide spectrum of neurological disorders. Through systematic evaluation of CSF’s physical, chemical, and cellular properties, clinicians can differentiate between infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, and haemorrhagic conditions affecting the CNS.

Physiology and Function of Cerebrospinal Fluid

Production and Circulation

CSF is primarily produced by the choroid plexus within the ventricles of the brain, at a rate of about 500 mL per day in adults. The total volume of CSF in an adult ranges from 120 to 150 mL. After production, CSF circulates through the ventricular system, flows into the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and is eventually absorbed into the venous system via arachnoid granulations.

Role in CNS

The functions of CSF are multifaceted:

- Mechanical Protection: CSF acts as a cushion, protecting the brain and spinal cord from trauma.

- Homeostasis: Maintains a stable chemical environment, including pH and electrolyte balance, essential for neuronal activity.

- Nutritional Support: Supplies nutrients and removes metabolic waste products.

- Immunological Defence: Contains immune cells and mediators that help defend against CNS infections.

Disruption in CSF physiology can lead to increased intracranial pressure, hydrocephalus, or altered composition, reflecting underlying disease processes.

Indications for CSF Examination

CSF analysis is indicated in various clinical scenarios, primarily when CNS infection, inflammation, haemorrhage, or malignancy is suspected. Key indications include:

- Suspected meningitis (bacterial, viral, fungal, or tuberculous)

- Encephalitis

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)

- Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases

- Malignancy involving the CNS (e.g., metastatic tumours, primary CNS lymphoma)

- Neurological symptoms of unclear origin (e.g., unexplained headache, altered consciousness, seizures)

- Investigation of CNS autoimmune diseases

The decision to perform CSF examination must balance diagnostic yield against potential risks, such as raised intracranial pressure or bleeding diatheses.

CSF Collection and Handling

Lumbar Puncture Technique

Lumbar puncture (LP) is the standard procedure for CSF collection. The patient is positioned either sitting or in lateral decubitus, and a sterile needle is introduced into the subarachnoid space, typically between the L3-L4 or L4-L5 vertebrae. Opening pressure is measured using a manometer, and CSF is collected into sterile containers for analysis.

Precautions and Contraindications

Key precautions include:

- Assess for signs of raised intracranial pressure (e.g., papilloedema, focal neurological deficits) to avoid risk of brain herniation.

- Correct coagulopathy to prevent spinal haematoma.

- Ensure aseptic technique to minimise infection risk.

Contraindications include local infection at puncture site, severe coagulopathy, and suspected intracranial mass effect.

Sample Management

CSF samples should be promptly transported to the laboratory. Tubes are allocated for different analyses:

- Biochemistry (protein, glucose, lactate)

- Microbiology (Gram stain, culture, PCR)

- Cytology (cell count, differential, malignant cells)

- Immunology (oligoclonal bands, antibodies)

Delayed processing or improper handling can alter results, leading to diagnostic errors.

Normal CSF Characteristics

Physical Features

Normal CSF is clear, colourless, and odourless. The opening pressure in adults is 60–200 mm H2O (0.6–2.0 kPa). Any turbidity or colour change suggests abnormality.

Chemical Composition

Key normal values include:

- Protein: 15–45 mg/dL

- Glucose: 45–80 mg/dL (usually about 60% of blood glucose)

- Lactate: 1.2–2.1 mmol/L

- Electrolytes: Sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium – similar to plasma but with minor differences

Microscopic Features

Normal CSF contains 0–5 lymphocytes/μL; no neutrophils or red blood cells (RBCs) should be present. The fluid is acellular, and no organisms or abnormal cells are seen.

Pathological Changes in CSF

Diverse disease processes can alter CSF characteristics. Recognising these changes is essential for diagnosis.

Alterations in Appearance

- Turbid CSF: Suggests increased cells (infection, inflammation).

- Xanthochromia: Yellowish coloration due to bilirubin, indicative of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) or old bleeding.

- Bloody CSF: Seen in traumatic tap or SAH.

Pressure Changes

- Raised pressure: Observed in meningitis, intracranial hypertension, or mass lesions.

- Low pressure: May occur in CSF leak or dehydration.

Cell Count Abnormalities

- Pleocytosis: Increased white blood cells (WBCs) in infection or inflammation.

- Neutrophilic predominance: Bacterial meningitis.

- Lymphocytic predominance: Viral, fungal, or tuberculous meningitis, and demyelinating diseases.

- RBCs: SAH, traumatic tap, or CNS bleeding.

Biochemical Abnormalities

- Elevated protein: Infection, inflammation, malignancy, or blood contamination.

- Decreased glucose: Bacterial, fungal, or tuberculous meningitis; neoplastic infiltration.

- Raised lactate: Suggests anaerobic metabolism, seen in bacterial meningitis and cerebral ischaemia.

Other Parameters

- Immunological markers: Oligoclonal bands indicate multiple sclerosis or other autoimmune CNS diseases.

- Microbial antigens: Detected by PCR, culture, or antigen detection methods.

Laboratory Analysis Techniques

CSF analysis is multi-faceted, involving cytological, biochemical, microbiological, and immunological investigations.

Cytology

- Cell count and differential are performed using a haemocytometer and microscopy.

- Detection of malignant cells is vital in CNS neoplasms.

- Special stains (e.g., Papanicolaou) aid in tumour identification.

Biochemistry

- Protein, glucose, and lactate measurements are automated or manual.

- Enzyme assays (e.g., lactate dehydrogenase) can be performed.

Microbiology

- Gram stain and culture remain gold standards for pathogen identification.

- Acid-fast staining for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Fungal stains (e.g., India ink for Cryptococcus).

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for rapid detection of viral and bacterial genomes.

Immunological Tests

- Oligoclonal band detection by electrophoresis.

- Autoantibody tests for autoimmune encephalitis.

- Antigen detection (e.g., cryptococcal antigen).

Timely and accurate laboratory analysis is crucial for reliable results.

Interpretation of CSF Findings

Interpretation of CSF results requires integration of clinical context, laboratory data, and imaging findings. Key principles include:

- Pattern recognition: Specific combinations of CSF abnormalities suggest particular diseases.

- Temporal changes: Serial CSF examinations can reveal disease progression or response to therapy.

- Correlation with systemic findings: Blood tests, imaging, and clinical features must be considered.

Common Pathological Conditions Diagnosed by CSF Examination

Meningitis

- Bacterial Meningitis: Turbid CSF, neutrophilic pleocytosis, elevated protein, low glucose, positive Gram stain and culture. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis are common pathogens.

- Viral Meningitis: Clear CSF, lymphocytic pleocytosis, normal or slightly elevated protein, normal glucose. PCR is useful for viral genome detection.

- Tuberculous Meningitis: Moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis, high protein, low glucose, positive acid-fast bacilli.

- Fungal Meningitis: Seen in immunocompromised patients; India ink stain for Cryptococcus, raised protein, low glucose.

Encephalitis

- Viral encephalitis (e.g., Herpes simplex virus) shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, mildly raised protein, and normal glucose. PCR aids diagnosis.

Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

- CSF is initially bloody, later xanthochromic. RBCs persist in all tubes. Elevated protein due to blood breakdown. CT scan and CSF analysis together confirm diagnosis.

Multiple Sclerosis

- Oligoclonal bands detected by electrophoresis, mild lymphocytic pleocytosis, and slightly raised protein. No infectious agents found.

Malignancy

- Malignant cells seen on cytology, elevated protein, and possibly low glucose. Metastatic carcinomas, lymphomas, and primary CNS tumours may be detected.

Other Conditions

- Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Albuminocytologic dissociation (high protein, normal cell count).

- CNS autoimmune diseases: Antibodies or specific markers may be present in CSF.

- Neurosyphilis: Lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, positive serology.

Case Studies and Examples

Case 1: Bacterial Meningitis in a Young Adult

A 24-year-old male presents with fever, headache, neck stiffness, and photophobia. Lumbar puncture yields turbid CSF with opening pressure of 250 mm H2O. Laboratory findings include neutrophilic pleocytosis (WBC 1200/μL, 95% neutrophils), protein 150 mg/dL, glucose 25 mg/dL (blood glucose 95 mg/dL), and positive Gram stain for Gram-positive diplococci. Diagnosis: Acute bacterial meningitis (likely Streptococcus pneumoniae). Immediate antibiotic therapy is initiated.

Case 2: Multiple Sclerosis Suspected in a Young Woman

A 30-year-old woman with recurrent episodes of visual disturbance and limb weakness undergoes CSF examination. Findings: Clear fluid, normal opening pressure, mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (WBC 12/μL), protein 60 mg/dL, glucose normal, and oligoclonal bands detected. MRI shows demyelinating plaques. Diagnosis: Multiple sclerosis. Disease-modifying therapy is started.

Case 3: Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Following Sudden Headache

A 50-year-old man presents with sudden, severe headache and altered sensorium. CT scan is equivocal. CSF obtained by lumbar puncture is uniformly bloody in all tubes, with xanthochromia after centrifugation. RBCs present, protein raised. Diagnosis: Subarachnoid haemorrhage due to ruptured aneurysm. Neurosurgical intervention follows.

Case 4: Cryptococcal Meningitis in an HIV-Positive Patient

A 35-year-old HIV-positive man presents with headache, fever, and confusion. CSF is clear, opening pressure elevated, lymphocytic pleocytosis, protein 100 mg/dL, glucose 30 mg/dL. India ink stain reveals encapsulated yeast cells. Diagnosis: Cryptococcal meningitis. Antifungal therapy is commenced.

Limitations and Pitfalls

Although CSF examination is invaluable, several limitations must be acknowledged:

- Traumatic tap: Accidental introduction of blood during LP can obscure findings.

- Delay in processing: Cellular and chemical changes may occur, affecting accuracy.

- False negatives: Low pathogen load or inappropriate tests may lead to missed diagnoses.

- Interpretation challenges: Overlapping findings in different diseases can complicate diagnosis.

- Risk to patient: Complications such as headache, infection, or bleeding may occur.

Close correlation with clinical and radiological data is essential to overcome these challenges.

REFERENCES

- Ramadas Nayak, Textbook of Pathology and Genetics for Nurses, 2nd Edition,2024, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-93-5270-031-8.

- Suresh Sharma, Textbook of Pharmacology, Pathology & Genetics for Nurses II, 2nd Edition, 31 August 2022, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-9354655692.

- Kumar, V., Abbas, A.K., & Aster, J.C. (2020). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 10th Edition. Elsevier.

- McCance, K.L., & Huether, S.E. (2018). Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 8th Edition. Elsevier.

- King O, West E, Lee S, Glenister K, Quilliam C, Wong Shee A, Beks H. Research education and training for nurses and allied health professionals: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022 May 19;22(1):385. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9121620/

- Barría P RM. Use of Research in the Nursing Practice: from Statistical Significance to Clinical Significance. Invest Educ Enferm. 2023 Nov;41(3):e12. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v41n3e12. PMID: 38589312; PMCID: PMC10990586.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.