Minimally Invasive Surgery: Revolutionizing Modern Medicine

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is a transformative advancement in modern medicine, representing a paradigm shift in the way surgical procedures are performed. By utilizing specialized techniques and technologies that reduce the size and number of incisions required, MIS has revolutionized patient care, offering reduced pain, quicker recovery, and superior outcomes compared to traditional open surgery.

Introduction to Minimally Invasive Surgery

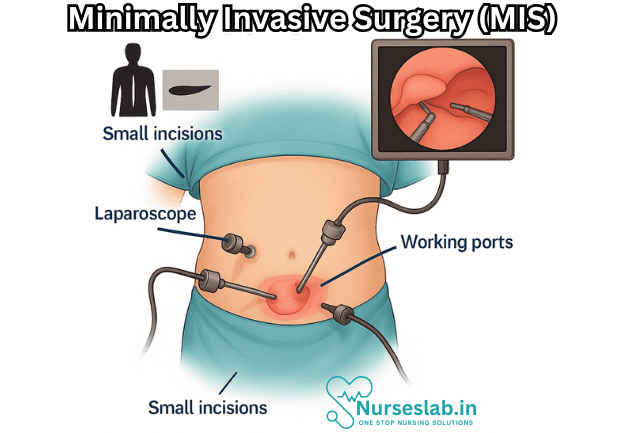

Minimally invasive surgery encompasses a wide array of procedures in which surgeons operate with less damage to the body than with traditional open surgery. Instead of large incisions exposing organs and tissues, MIS typically involves small cuts, through which surgeons insert specialized instruments and cameras to perform procedures with precision. This approach is widely used across many surgical disciplines, including general surgery, orthopedics, urology, gynecology, cardiothoracic surgery, and neurosurgery.

Historical Evolution of MIS

The concept of minimizing surgical trauma dates back centuries, but true minimally invasive surgery emerged in the late 20th century with the development of fiber optics and video technology. The introduction of laparoscopy in the 1980s marked a watershed moment. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) quickly became the standard because patients experienced significantly less postoperative pain and faster recovery. Since then, advances in instrumentation, imaging, and robotics have expanded the scope and application of MIS.

Techniques and Technologies in MIS

Minimally invasive surgery relies on several key techniques and technologies:

- Laparoscopy: This technique involves the insertion of a thin tube called a laparoscope, equipped with a camera and light source, through small incisions in the abdomen. Surgeons view the operative field on a video monitor and manipulate long, slender instruments to perform the procedure.

- Endoscopy: Similar to laparoscopy but applied to hollow organs, endoscopy allows visualization and intervention within the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory system, or urinary tract using flexible or rigid scopes.

- Arthroscopy: Used in joint surgery (e.g., knee, shoulder), arthroscopy involves inserting a camera and instruments through tiny incisions to diagnose and treat joint problems.

- Thoracoscopy: Minimally invasive technique for chest surgery, allowing access to the lungs, heart, and mediastinum.

- Robotic-assisted surgery: The advent of surgical robots, such as the da Vinci Surgical System, has elevated MIS precision. Surgeons operate from a console, controlling robotic arms equipped with tools and cameras, which translate their movements into highly precise actions.

- Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES): This cutting-edge approach uses natural body openings (mouth, anus, vagina) to access internal organs, further reducing trauma and external scarring.

Advantages of Minimally Invasive Surgery

MIS offers numerous benefits compared to traditional open surgery:

- Reduced Pain: Smaller incisions decrease tissue damage and postoperative discomfort.

- Faster Recovery: Patients typically experience shorter hospital stays and quicker return to normal activities.

- Lower Risk of Infection: With less exposure of internal tissues, the likelihood of wound infection and other complications is diminished.

- Minimal Scarring: Tiny incisions result in less visible scarring, which is aesthetically preferable for many patients.

- Decreased Blood Loss: Precise instruments and visualization help surgeons minimize bleeding during procedures.

- Improved Visualization: Cameras provide magnified, high-definition views of the operative field, enhancing surgical precision.

Common Procedures Performed Using MIS

Minimally invasive techniques now span a wide variety of surgical interventions, including:

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal)

- Appendectomy (appendix removal)

- Hernia repair

- Colectomy (partial or total removal of the colon)

- Hysterectomy (removal of the uterus)

- Prostatectomy (removal of the prostate)

- Coronary artery bypass (minimally invasive cardiac surgery)

- Spinal fusion and other neurosurgical procedures

- Joint repairs via arthroscopy

Patient Selection and Preparation

While MIS is suitable for many patients, it is not universally applicable. Proper patient selection is critical:

- Medical History: Surgeons assess underlying health conditions, previous surgeries, and anatomical considerations.

- Imaging: Preoperative imaging (CT, MRI, ultrasound) helps map the surgical field and plan minimally invasive access.

- Preoperative Counseling: Patients are educated about the procedure, recovery expectations, and risks.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its advantages, MIS presents certain limitations and challenges:

- Learning Curve: Surgeons require specialized training and experience to master MIS techniques.

- Equipment Costs: Advanced instruments and robotic systems can be expensive, limiting accessibility in resource-constrained settings.

- Procedure Complexity: Some surgeries are too complex or risky to be performed using MIS, necessitating traditional open approaches.

- Conversion Risk: In certain cases, minimally invasive procedures may need to be converted to open surgery due to unexpected complications or anatomy.

Postoperative Care and Recovery

Recovery after minimally invasive surgery is generally quicker and less painful than open surgery. Key aspects include:

- Pain Management: Most patients require less pain medication and experience fewer side effects.

- Early Mobilization: Faster recovery encourages early movement, reducing the risk of blood clots and muscle loss.

- Shorter Hospital Stay: Many patients are discharged within 24-48 hours, and some procedures are performed on an outpatient basis.

- Follow-up: Regular postoperative visits ensure proper healing and monitor for complications.

Impact on Healthcare Systems

The widespread adoption of MIS has far-reaching effects on healthcare delivery:

- Cost Savings: Quicker recoveries and shorter hospital stays reduce overall healthcare costs.

- Resource Efficiency: Operating rooms may require less time per procedure, increasing throughput and access to care.

- Patient Satisfaction: Improved outcomes and cosmetic results enhance patient satisfaction.

Recent Innovations in Minimally Invasive Surgery

Advances continue to push the boundaries of MIS:

- Fluorescence Imaging: Enhanced visualization of blood vessels and tissues using special dyes and light.

- Augmented Reality (AR): Integration of AR overlays with surgical cameras to guide complex interventions.

- Single-incision Laparoscopic Surgery (SILS): Performing operations through one small incision instead of several.

- Magnetic Surgery: Use of magnets to manipulate instruments inside the body without additional cuts.

Training and Education

The success of MIS hinges on rigorous training and continuous education for surgeons:

- Simulation Labs: Surgeons practice MIS techniques using high-fidelity simulators before operating on patients.

- Fellowships: Specialized training programs in minimally invasive and robotic surgery.

- Ongoing Education: Regular attendance at workshops, conferences, and skills courses to keep abreast of innovations.

Nursing Care of Patients Undergoing Minimally Invasive Surgery

The unique characteristics of MIS require nurses to adapt their care approach, focusing on precise perioperative assessment, specialized patient education, vigilant monitoring, and comprehensive psychosocial support.

Preoperative Nursing Care

1. Patient Assessment

A thorough preoperative assessment is critical. Nurses should:

- Obtain a comprehensive medical, surgical, and medication history.

- Assess for comorbidities that may increase surgical risk (e.g., diabetes, cardiopulmonary disease).

- Evaluate for factors that could complicate MIS (e.g., obesity, previous abdominal surgeries, bleeding disorders).

2. Patient Education

Education is key to alleviating anxiety and ensuring patient cooperation. Preoperative teaching should include:

- Explanation of the MIS procedure, its benefits, and potential risks.

- Information about the expected length of the surgery and recovery process.

- Instructions on preoperative fasting, medication adjustments, and bowel preparation if required.

- What to expect in the operating room, including equipment and monitoring devices.

- Postoperative care, pain management strategies, and early mobilization expectations.

Effective teaching should be patient-centered, using language appropriate to the patient’s age, literacy, and cultural background. Providing written materials or digital resources reinforces understanding.

3. Psychosocial Support

Preoperative anxiety is common. Nurses can provide emotional support by:

- Encouraging questions and addressing concerns or misconceptions.

- Facilitating communication between the patient, family, and surgical team.

- Assessing and supporting coping mechanisms and spiritual needs.

Intraoperative Nursing Care

1. Operating Room Preparation

Nurses play a vital role in preparing the OR for MIS:

- Ensuring availability and sterility of specialized instruments and equipment (e.g., laparoscopes, insufflators, robotic systems).

- Preparing appropriate surgical positioning devices and ensuring patient safety to prevent nerve damage or pressure injuries.

- Verifying correct patient identity, surgical site, and procedure (time-out protocol).

2. Patient Positioning and Monitoring

MIS often requires unique patient positioning (e.g., Trendelenburg, lithotomy). Nurses must:

- Ensure appropriate padding and support to prevent pressure ulcers and nerve injuries.

- Continuously monitor vital signs, oxygenation, and signs of adverse reactions (e.g., to anesthesia or CO₂ insufflation).

- Assist in the application of sequential compression devices to prevent venous thromboembolism.

3. Aseptic Technique and Infection Prevention

Strict adherence to aseptic technique is essential due to the use of specialized ports and equipment. Nurses should:

- Maintain a sterile field and handle instruments appropriately.

- Monitor for any breaches in sterility and intervene immediately if contamination occurs.

Postoperative Nursing Care

1. Immediate Postoperative Assessment

After MIS, patients are transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) for close observation. Nursing priorities include:

- Monitoring airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs).

- Assessing pain using standardized pain scales and providing appropriate analgesia.

- Observing for early signs of complications such as bleeding, infection, or adverse reactions to anesthesia.

- Monitoring surgical incisions for signs of bleeding, swelling, or discharge.

- Assessing for nausea and vomiting, which are common after MIS due to anesthesia and CO₂ insufflation.

2. Pain Management

Pain after MIS is usually less severe than after open surgery but can still be significant. Nurses should:

- Administer prescribed analgesics as needed, considering both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (e.g., positioning, cold therapy, relaxation techniques).

- Educate patients on realistic pain expectations and encourage communication about pain levels.

3. Early Mobilization and Respiratory Care

Early mobilization is critical to prevent complications such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism. Nurses should:

- Encourage and assist the patient to sit up, dangle legs, and eventually ambulate as soon as it is safe to do so—often within hours after surgery.

- Instruct in and assist with incentive spirometry and deep breathing exercises to prevent pneumonia and atelectasis.

4. Fluid and Nutrition Management

Depending on the procedure and patient status, resumption of oral intake is often quicker after MIS. Nurses should:

- Monitor for return of bowel sounds and assess for tolerance to oral fluids and food.

- Gradually advance the diet as tolerated, starting with clear liquids.

- Monitor input and output to assess for adequate hydration and kidney function.

5. Wound and Drain Care

MIS incisions are small but still require careful observation. Nursing care includes:

- Inspecting wound sites for redness, swelling, excessive drainage, or signs of infection.

- Teaching patients and families correct wound care and signs of complications to report.

- Caring for and monitoring surgical drains if present, including recording output and maintaining patency.

6. Education for Discharge and Home Care

Safe discharge depends on comprehensive patient and family education. Key topics include:

- Proper wound care, activity limitations, and signs of complications (e.g., fever, increasing pain, redness or discharge at incision sites).

- Instructions on pain medication, follow-up appointments, and resumption of normal diet and activity.

- When to contact the healthcare provider or return to the hospital (e.g., for severe pain, uncontrolled nausea/vomiting, signs of infection).

Complications and Their Management

While MIS is generally safe, some complications can occur. Nurses must be vigilant for:

- Bleeding: Monitor for tachycardia, hypotension, pallor, or visible bleeding at incision sites.

- Infection: Watch for fever, redness, swelling, and purulent drainage.

- Deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: Assess for calf pain, swelling, shortness of breath, or chest pain.

- Pneumothorax (in thoracic procedures): Monitor for sudden respiratory distress, decreased breath sounds, or hypoxia.

- Anesthesia-related complications: Recognize and report symptoms such as allergic reactions, persistent nausea/vomiting, or delayed awakening.

- Organ or vessel injury: Be alert to unexplained pain, abdominal distention, or signs of internal bleeding.

Early recognition and prompt intervention are crucial in minimizing harm and promoting optimal outcomes.

Pediatric and Geriatric Considerations

Both pediatric and elderly patients require special attention:

- Pediatric patients: Dosing of medications, psychological preparation, and family involvement must be tailored to the child’s age and developmental level.

- Geriatric patients: Pre-existing comorbidities, cognitive impairment, frailty, and greater risk of delirium or falls necessitate individualized perioperative planning and enhanced post-discharge support.

Psychosocial and Cultural Considerations

Holistic nursing care accounts for the patient’s emotional, social, and cultural context. Nurses should:

- Assess and support coping strategies; refer to counseling or support groups if needed.

- Use interpreters or culturally appropriate materials for non-native speakers.

- Respect privacy, modesty, and cultural preferences in all aspects of care.

Role of Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Effective care for MIS patients involves collaboration with:

- Surgical team (surgeons, anesthesiologists)

- Pharmacists (medication management)

- Physical and occupational therapists (early mobilization and rehabilitation)

- Dietitians (nutrition guidance)

- Social workers and case managers (post-discharge planning)

Clear communication and shared decision-making enhance patient safety and satisfaction.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/minimally-invasive-spine-surgery/.

- Han ES, et al. Safety in minimally invasive surgery. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2019; doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2019.01.013.

- Buia A, Stockhausen F, Hanisch E. Laparoscopic surgery: A qualified systematic review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4686422/. World J Methodol. 2015 Dec 26;5(4):238-54.

- Navaratnam A, et al. Updates in urologic robot assisted surgery [version 1; peer review: 2 approved. F1000 Research. 2022; doi:10.12688/f1000research.15480.1.

- Mohiuddin K, Swanson SJ. Maximizing the benefit of minimally invasive surgery. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24037974/. J Surg Oncol. 2013 Oct;108(5):315-9.

- Spight DH, Jobe BA, Hunter JG. Minimally Invasive Surgery, Robotics, Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery, and Single-Incision Laparoscopic Surgery. In: Brunicardi F, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, et al, eds. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 11th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Hu YX, et al. Esophageal hiatal hernia: Risk, diagnosis and management. Expert Review of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2018; doi:10.1080/17474124.2018.1441711.

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.