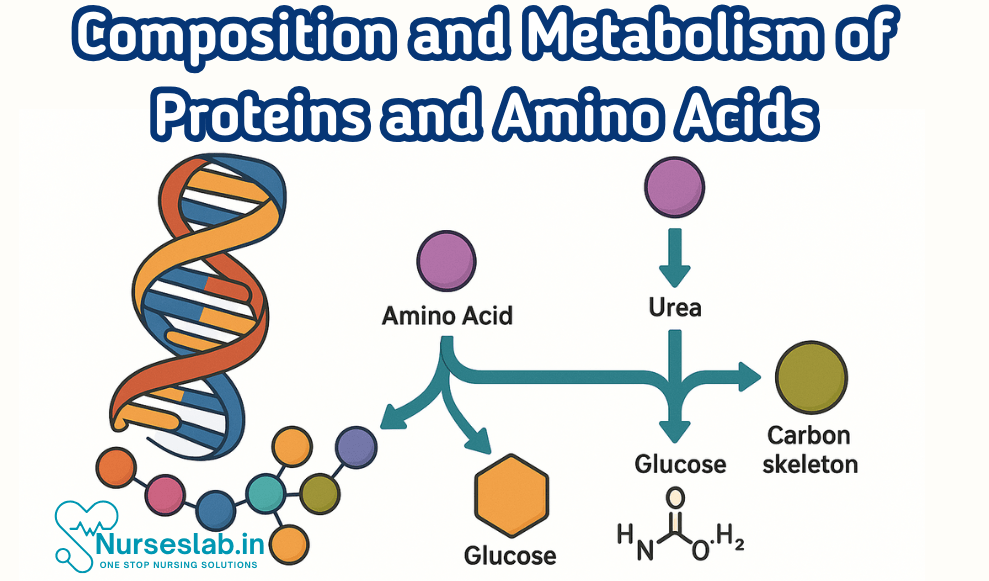

The composition of proteins includes chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Their metabolism involves digestion into amino acids, absorption in the intestine, and pathways for synthesis, catabolism, and energy production. Essential for tissue repair, enzymes, and hormones.

Introduction:

Proteins and amino acids are foundational to virtually every physiological process, from tissue repair to immune response, making their study essential for effective nursing practice. Among the myriad of biomolecules, proteins and amino acids stand out due to their multifaceted roles in structure, function, and metabolism.

Composition of Proteins

Definition of Proteins

Proteins are large, complex molecules composed of one or more chains of amino acids. They are the most abundant organic molecules in cells, serving as the main structural and functional components of living tissues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions, including catalysis of biochemical reactions, transport of molecules, and provision of structural support.

Elements and Chemical Composition

Proteins are primarily made up of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N). Some proteins also contain sulfur (S), phosphorus (P), and trace elements such as iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and zinc (Zn). The basic building blocks of proteins are amino acids, which link together via peptide bonds to form polypeptide chains.

Each amino acid features a central carbon atom (the alpha carbon) attached to an amino group (-NH2), a carboxyl group (-COOH), a hydrogen atom, and a variable side chain (R group) that distinguishes one amino acid from another.

Levels of Protein Structure

The structure of proteins is classified into four hierarchical levels:

- Primary Structure: The linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain, determined by genetic code.

- Secondary Structure: Local folding patterns such as alpha-helices and beta-pleated sheets, stabilised by hydrogen bonds.

- Tertiary Structure: The overall three-dimensional shape formed by the entire polypeptide chain, resulting from interactions among side chains (hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonds, disulphide bridges).

- Quaternary Structure: The assembly of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) into a functional protein complex, such as haemoglobin.

Types of Proteins

- Simple Proteins: Composed solely of amino acids. Examples include albumin, globulin, and histones.

- Conjugated Proteins: Contain amino acids plus a non-protein component (prosthetic group), such as glycoproteins, lipoproteins, and metalloproteins.

- Derived Proteins: Formed from the partial hydrolysis of simple and conjugated proteins, such as peptones and proteoses.

Amino Acids

Definition and General Structure

Amino acids are organic compounds that serve as the monomers of proteins. Each amino acid consists of a central alpha carbon atom bonded to an amino group, a carboxyl group, a hydrogen atom, and a distinctive side chain (R group) that determines its properties.

Classification of Amino Acids

- Essential Amino Acids: Cannot be synthesised by the human body and must be obtained through diet. Examples include leucine, isoleucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine.

- Non-Essential Amino Acids: Can be synthesised by the body. Examples include alanine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and serine.

- Semi-Essential Amino Acids: Required in the diet during periods of growth or illness. Examples include arginine and histidine (especially important in children).

Properties of Amino Acids

Amino acids display a range of physical and chemical properties:

- Solubility: Most amino acids are soluble in water due to their polar groups.

- Optical Activity: Except for glycine, all amino acids are optically active, existing as L- or D-isomers. Only L-amino acids are incorporated into proteins.

- Acid-Base Behaviour: Amino acids are amphoteric, meaning they can act as both acids and bases. At physiological pH, they exist as zwitterions, carrying both positive and negative charges.

Peptide Bond Formation

A peptide bond is a covalent bond formed between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of another, releasing a molecule of water. This process, known as condensation, links amino acids into polypeptide chains, which fold to form functional proteins.

Functions of Proteins

Proteins are indispensable for the normal functioning of the body, serving multiple roles:

- Structural Roles: Proteins like collagen and keratin provide strength and support to tissues such as skin, hair, nails, and bones.

- Enzymatic Functions: Most enzymes are proteins that catalyse biochemical reactions, essential for metabolism, digestion, and cellular signalling.

- Transport and Storage: Haemoglobin transports oxygen, while albumin and ferritin store and transport nutrients and minerals.

- Hormonal and Regulatory Functions: Many hormones, such as insulin and growth hormone, are proteins that regulate physiological processes.

- Immune Response: Antibodies (immunoglobulins) are proteins that recognise and neutralise pathogens, forming a key part of the immune system.

Digestion and Absorption of Proteins

Overview of Protein Digestion

Protein digestion is a multi-step process that begins in the mouth and continues through the stomach and small intestine:

- Mouth: Mechanical breakdown of food, but no significant chemical digestion of proteins.

- Stomach: Gastric glands secrete hydrochloric acid and the enzyme pepsin. Acid denatures proteins, making them more accessible for enzymatic cleavage. Pepsin breaks proteins into smaller polypeptides.

- Small Intestine: Pancreatic enzymes (trypsin, chymotrypsin, carboxypeptidase) and intestinal enzymes (aminopeptidases, dipeptidases) further hydrolyse polypeptides into amino acids and small peptides.

Enzymes Involved in Protein Digestion

- Pepsin: Initiates protein digestion in the stomach by cleaving peptide bonds.

- Trypsin and Chymotrypsin: Secreted by the pancreas, they act in the small intestine to break down polypeptides.

- Carboxypeptidase: Removes amino acids from the carboxyl end of peptides.

- Aminopeptidases and Dipeptidases: Complete the digestion of peptides into free amino acids at the brush border of the intestinal mucosa.

Absorption Mechanisms

Amino acids and small peptides are absorbed primarily in the small intestine. Specific carrier proteins in the intestinal epithelial cells facilitate the active transport of amino acids into the bloodstream. Dipeptides and tripeptides may also be absorbed and further hydrolysed within the cells.

Metabolism of Amino Acids

Transamination and Deamination

- Transamination: The process by which amino groups are transferred from one amino acid to a keto acid, forming a new amino acid. This is essential for the synthesis of non-essential amino acids.

- Deamination: The removal of an amino group from an amino acid, producing ammonia and a keto acid. Ammonia is toxic and must be converted to urea for safe excretion.

The Urea Cycle

The urea cycle is a series of biochemical reactions in the liver that convert toxic ammonia into urea, which is then excreted by the kidneys. The cycle involves several enzymes and intermediate compounds, ensuring the safe removal of nitrogen waste from the body.

- Step 1: Ammonia combines with carbon dioxide to form carbamoyl phosphate.

- Step 2: Carbamoyl phosphate reacts with ornithine to produce citrulline.

- Step 3: Citrulline combines with aspartate to form argininosuccinate.

- Step 4: Argininosuccinate splits into arginine and fumarate.

- Step 5: Arginine is hydrolysed to produce urea and regenerate ornithine.

Fate of Carbon Skeletons

After deamination, the carbon skeletons of amino acids can be utilised in various metabolic pathways:

- Glucogenic Amino Acids: Converted into glucose via gluconeogenesis.

- Ketogenic Amino Acids: Converted into ketone bodies, used as an energy source during fasting or low carbohydrate intake.

- Energy Production: Carbon skeletons may enter the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to produce ATP.

Synthesis of Non-Essential Amino Acids

Non-essential amino acids are synthesised in the body through transamination and other pathways, utilising intermediates from glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and other metabolic routes. This synthesis is vital for maintaining protein turnover and metabolic flexibility.

Clinical Relevance

Protein-Energy Malnutrition

Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) is a significant health concern, especially in children and vulnerable populations. It manifests as conditions such as kwashiorkor (due to protein deficiency) and marasmus (due to overall calorie deficiency). Symptoms include muscle wasting, oedema, stunted growth, and impaired immune function.

Inborn Errors of Amino Acid Metabolism

- Phenylketonuria (PKU): Caused by a deficiency of phenylalanine hydroxylase, leading to the accumulation of phenylalanine and its toxic metabolites. Untreated PKU results in intellectual disability and neurological problems. Early detection and dietary management are essential.

- Alkaptonuria: Caused by a deficiency of homogentisic acid oxidase, leading to the accumulation of homogentisic acid, which darkens urine and causes joint and connective tissue problems.

Proteinuria and Kidney Function

Proteinuria, the presence of excess protein in urine, is an important clinical indicator of kidney dysfunction. It can result from glomerular damage, infections, diabetes, or hypertension. Persistent proteinuria requires medical evaluation and management to prevent progression to chronic kidney disease.

Importance in Wound Healing and Recovery

Adequate protein intake is vital for wound healing and recovery from illness or surgery. Proteins provide the building blocks for cell proliferation, tissue repair, and immune defence. Nurses should monitor patients’ nutritional status and advocate for protein-rich diets during periods of increased physiological demand.

Practical Implications for Nursing Practice

- Assess patients’ dietary protein intake and identify risk factors for malnutrition.

- Monitor signs of metabolic disorders and collaborate with multidisciplinary teams for effective management.

- Educate patients and families about the importance of protein-rich diets, especially during growth, illness, or recovery.

- Stay updated with clinical guidelines and advancements in the understanding of protein and amino acid metabolism.

REFERENCES

- Harbans Lal, Textbook of Applied Biochemistry and Nutrition& Dietetics 2nd Edition ,November 2024, CBS Publishers and Distributors, ISBN: 978-9394525757

- Suresh K Sharma, Textbook of Biochemistry and Biophysics for Nurses, 2nd Edition, September 2022, Jaypee Publishers, ISBN: 978-9354655760

- Peter J Kennelly, Harpers Illustrated Biochemistry Standard Edition, September 2022, McGraw Hill Lange Publishers, ISBN: 978-1264795673

- Denise R Ferrier, Ritu Singh, Lippincott Illustrated Reviews Biochemistry, Second Edition, June 2024, ISBN- 978-8197055973

- Yadav, Tapeshwar & Bhadeshwar, Sushma. (2022). Essential Textbook of Biochemistry for Nursing.

- Applied Sciences, Importance of Biochemistry for Nursing Practice, November 2, 2023, https://bns.institute/applied-sciences/importance-biochemistry-nursing-practice/

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.