Introduction

Local anaesthesia is a cornerstone of modern medicine, allowing for painless surgical and diagnostic procedures without the need for general anesthesia. By targeting a specific area of the body, local anesthetics enable physicians and surgeons to block sensation, ensuring patient comfort and safety. The advent and continual refinement of local anesthetic techniques have vastly expanded the possibilities of minor and major medical interventions, contributing significantly to advancements in patient care.

What is Local Anesthesia?

Local anesthesia refers to the temporary loss of sensation or pain in a specific part of the body, achieved through the application or injection of anesthetic agents. Unlike general anesthesia, which induces unconsciousness and affects the entire body, local anesthesia is confined to a single area, allowing the patient to remain awake and alert throughout the procedure.

Key Features of Local Anesthesia:

- Targeted numbing of a specific region.

- Patient remains conscious and responsive.

- Reduced systemic side effects compared to general anesthesia.

- Rapid onset and recovery.

History and Development

The first recorded use of local anesthesia dates back to the late 19th century. Cocaine, derived from coca leaves, was the earliest local anesthetic used in medical practice. Its success prompted the development of safer synthetic alternatives, such as procaine (Novocain) and, later, lidocaine, which remain widely used today.

Milestones in Local Anesthesia:

- 1884: Carl Koller utilizes cocaine for ophthalmic (eye) surgery, pioneering local anesthesia.

- 1905: Procaine (Novocain) is synthesized, providing a safer alternative to cocaine.

- 1943: Lidocaine is introduced, offering greater potency and lower toxicity.

- Continuous advances have produced a range of agents with varying onset, duration, and potency.

Types of Local Anesthesia

There are several forms of local anesthesia, each suited to specific procedures and patient needs:

Topical Anesthesia

This involves the direct application of anesthetic agents (creams, gels, sprays, or drops) to the skin or mucous membranes to numb the surface. Commonly used for minor skin procedures, eye procedures, and dental work.

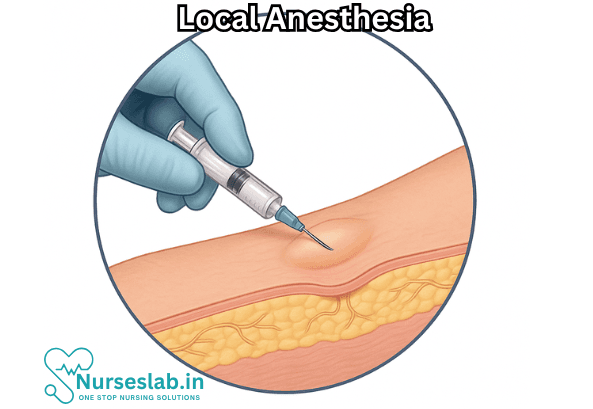

Infiltration Anesthesia

The anesthetic is injected directly into the tissue around the surgical site. This method is widely used in dentistry, minor skin surgery, and laceration repair.

Nerve Block

An anesthetic is injected near a specific nerve or group of nerves to block sensation in a larger area. Nerve blocks are invaluable for procedures on the limbs, face, or during childbirth.

Regional Anesthesia

A broader term that includes nerve blocks and other techniques (such as spinal or epidural anesthesia), which numb an entire region of the body. Regional anesthesia sits between local and general anesthesia in scope and is often used in orthopedic surgeries.

Mechanism of Action

Local anesthetics work by interfering with the conduction of nerve impulses. Normally, nerves transmit signals via electrical impulses generated by ion movement, especially sodium ions, across nerve cell membranes. Local anesthetics block sodium channels, preventing the initiation and propagation of these impulses, and thus, eliminating sensations of pain and temperature in the targeted area.

Common Local Anesthetic Agents

A variety of drugs are employed as local anesthetics, each with unique properties regarding onset, duration, potency, and side effects.

- Lidocaine: The most commonly used local anesthetic, suitable for a wide range of procedures; rapid onset and moderate duration.

- Bupivacaine: Longer-acting than lidocaine; often used for nerve blocks and epidurals.

- Articaine: Frequently used in dentistry due to its effectiveness in oral tissues.

- Prilocaine: Used in combination with other agents for skin procedures.

- Mepivacaine and Ropivacaine: Alternatives with specific applications based on patient needs and procedure duration.

Clinical Uses of Local Anesthesia

Local anesthesia is employed in a broad spectrum of medical disciplines:

- Dermatology: Removal of skin lesions, mole excisions, biopsies, and minor cosmetic procedures.

- Dentistry: Tooth extractions, fillings, root canals, and gum surgeries.

- Ophthalmology: Cataract surgery, corneal procedures, and minor eye repairs.

- Obstetrics: Nerve blocks for labor pain and minor gynecological surgeries.

- Orthopedics: Setting fractures, joint injections, and soft tissue repairs.

- Podiatry: Ingrown toenail removal, foot surgeries, and wound care.

- General Surgery: Laceration repair, abscess drainage, and superficial surgical interventions.

Advantages of Local Anesthesia

Local anesthesia offers numerous benefits over general anesthesia or sedation:

- Safety: Reduced risk of systemic complications, such as respiratory depression or post-operative nausea.

- Faster Recovery: Patients can often return home shortly after the procedure.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Typically less expensive due to the absence of general anesthesia equipment and monitoring.

- Patient Comfort: Avoids loss of consciousness and associated side effects.

- Flexibility: Can be repeated or adjusted as needed during the procedure.

Risks and Complications

Despite its safety profile, local anesthesia is not without risks:

- Local Reactions: Pain, bruising, swelling, or infection at the injection site.

- Allergic Reactions: Rare but possible, especially with ester-type anesthetics.

- Toxicity: Accidental injection into a blood vessel can cause systemic toxicity, leading to symptoms such as dizziness, seizures, or cardiac disturbances.

- Nerve Injury: Uncommon but possible, especially with nerve blocks.

- Methemoglobinemia: A rare blood disorder associated with certain anesthetics like prilocaine and benzocaine.

Patient Preparation and Aftercare

- Proper patient preparation and aftercare are vital for minimizing risks and ensuring successful outcomes:

- Instructions regarding wound care, activity restrictions, and signs of complications.

- Thorough medical history to identify allergies and contraindications.

- Clear explanation of the procedure and what to expect during and after anesthesia.

- Post-procedure monitoring for adverse effects.

Nursing Care of a Patient Undergoing Local Anesthesia

Nursing care plays a critical role in ensuring the patient’s safety, comfort, and optimal outcomes before, during, and after administration of local anesthesia.

Nursing Responsibilities: Pre-Procedure

Patient Assessment

- Obtain a thorough medical history, including allergies (especially to local anesthetics), current medications, and previous experiences with anesthesia.

- Evaluate for contraindications, such as infection at the site of injection, bleeding disorders, or severe systemic disease.

- Assess the patient’s understanding of the planned procedure and address any questions or anxieties.

Preparation and Consent

- Explain the procedure, expected sensations (e.g., stinging, pressure), and the purpose of local anesthesia.

- Ensure informed consent is obtained and documented according to institutional policy.

- Verify that all equipment and emergency supplies (e.g., resuscitation equipment, medications for allergic reactions) are available and functional.

Site Preparation

- Assist in identifying and marking the correct procedure site.

- Ensure skin cleanliness and assist with antiseptic preparation to reduce infection risk.

- Position the patient appropriately for both comfort and optimal access to the site.

Nursing Care: Intra-Procedure

Patient Support and Monitoring

- Provide reassurance and maintain a calm environment.

- Monitor the patient’s vital signs, level of comfort, and overall response throughout the procedure.

- Observe for signs of adverse reactions, such as sudden changes in consciousness, rash, itchiness, respiratory distress, or cardiovascular symptoms (tachycardia, hypotension).

Assisting the Provider

- Prepare and hand over sterile instruments and anesthetic agents as required.

- Assist in administering the local anesthetic, adhering to aseptic technique at all times.

- Document the type, amount, and site of anesthesia administration.

Managing Patient Comfort

- Monitor for pain or discomfort during the injection or procedure; provide distraction or support as needed.

- Observe for signs of insufficient anesthesia, such as movement or verbalization of pain, and report to the provider promptly.

Nursing Care: Post-Procedure

Observation for Complications

- Monitor the patient for delayed allergic reactions, signs of infection at the injection site, hematoma, or nerve injury.

- Assess for systemic toxicity, especially with large doses or inadvertent intravascular injection; symptoms may include CNS disturbances (e.g., dizziness, confusion, seizures) and cardiovascular effects (e.g., arrhythmias, hypotension).

Pain and Sensation Assessment

- Evaluate the return of normal sensation and motor function in the anesthetized area.

- Assess the effectiveness of the anesthesia in controlling post-procedural pain and provide additional pain management if necessary.

Wound and Site Care

- Inspect the procedure site for bleeding, swelling, discharge, or signs of infection.

- Apply dressings as required and ensure the site remains clean and protected.

Patient Education

- Instruct the patient regarding expected duration of numbness and the importance of protecting the anesthetized area from injury (e.g., avoiding hot or sharp objects, not chewing food until oral numbness resolves).

- Provide written and verbal instructions on signs and symptoms that should prompt medical attention (e.g., persistent numbness, swelling, severe pain, fever, rash, shortness of breath).

- Review wound care instructions and follow-up appointments.

Documentation

Record all relevant information, including time, type and amount of anesthetic used, site of administration, patient response, and any adverse events or interventions undertaken.

Special Considerations

Pediatric and Geriatric Patients

- Children and elderly patients may require additional reassurance and support due to anxiety, communication barriers, or increased sensitivity to anesthetics.

- Dosages should be carefully calculated based on age, weight, and comorbidities to minimize the risk of toxicity.

Patients with Preexisting Medical Conditions

- Assess for conditions that may increase risk, such as liver or cardiac disease, which can alter anesthetic metabolism or increase adverse effects.

Patients with Anxiety or Needle Phobia

- Employ distraction techniques, clear explanations, and supportive presence to minimize distress and improve cooperation during the procedure.

Emergency Management

Nurses must be prepared to recognize and respond to emergencies associated with local anesthesia, even though serious complications are rare. Immediate intervention is necessary in cases of:

- Allergic Reactions: Symptoms include hives, difficulty breathing, facial or throat swelling. Administer emergency medications (antihistamines, corticosteroids, epinephrine) as per protocol and summon emergency help.

- Systemic Toxicity: CNS toxicity may manifest as tinnitus, perioral numbness, metallic taste, agitation, or seizures. Cardiac toxicity can present as arrhythmias or cardiac arrest. Initiate supportive care, airway management, and advanced resuscitation protocols as needed.

- Vasovagal Reactions: Some patients may experience fainting or hypotension due to anxiety or pain. Place the patient in a supine position, elevate the legs, and monitor vital signs until recovery.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

- Ensure that the patient’s autonomy and rights are respected throughout the perioperative period.

- Maintain confidentiality, privacy, and dignity at all times.

- Document all care, interventions, and patient responses accurately and promptly.

- Comply with institutional policies, professional standards, and legal requirements regarding administration and monitoring of local anesthesia.

REFERENCES

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Local Anesthesia. https://www.asahq.org/madeforthismoment/anesthesia-101/types-of-anesthesia/local-anesthesia/.

- Garmon EH, Huecker MR. Topical, Local, and Regional Anesthesia and Anesthetics (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430894/). 2023 Aug 28. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan.

- Tobe M, Suto T, Saito S. The history and progress of local anesthesia: multiple approaches to elongate the action. J Anesth. 2018;32(4):632-636. doi:10.1007/s00540-018-2514-8

- Mahajan A, Derian A. Local Anesthetic Toxicity. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499964/. 2022 Oct 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan.

- Garmon EH, Hendrix JM, Huecker MR. Topical, Local, and Regional Anesthesia and Anesthetics. [Updated 2025 Feb 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430894/

- National Health Service (UK). Local Anesthesia. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/local-anaesthesia/). Last reviewed 1/23/2022.

- Reece-Stremtan S, Campos M, Kokajko L; Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM clinical protocol #15: analgesia and anesthesia for the breastfeeding mother, Updated 2017. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12(9):500-506. doi:10.1089/bfm.2017.29054.srt

Stories are the threads that bind us; through them, we understand each other, grow, and heal.

JOHN NOORD

Connect with “Nurses Lab Editorial Team”

I hope you found this information helpful. Do you have any questions or comments? Kindly write in comments section. Subscribe the Blog with your email so you can stay updated on upcoming events and the latest articles.